Most people find new office space on a tour with a commercial broker or by trawling websites featuring photos and floor plans. Not the tenants at 161 Water Street. They were recruited. The editor of Office Magazine met the management team at a dinner in Paris. Devin B. Johnson, a figurative painter, was tapped by an art curator. Many more learned about the building while vacationing in the Cayman Islands — specifically, while vacationing at Palm Heights, a beachfront hotel run by the British couple Matthew and Gabriella Khalil. “I would have never ever, never ever thought that I would end up here,” said Michael Goldberg, who leads the marketing firm Something Special Studios and recently moved in his staff from the Lower East Side after connecting with the Khalils at Palm Heights. “Fidi wasn’t exactly an area I was targeting.”

161 Water Street, a 700,000-square-foot, 31-story tower being rebranded as WSA, for Water Street Associates, is in one of the least alluring parts of the Financial District — a wide, windblown stretch where its corporate neighbors include S&P Global and EmblemHealth. Even here, the building is particularly corporate, a 1982 temple of reddish marble and curving tinted glass. Then there’s the building’s past. It’s better known by its former address, 175 Water Street, which it went by as the headquarters of AIG, the insurer that backed subprime mortgages, got bailout money, and then handed out bonuses to its executives.

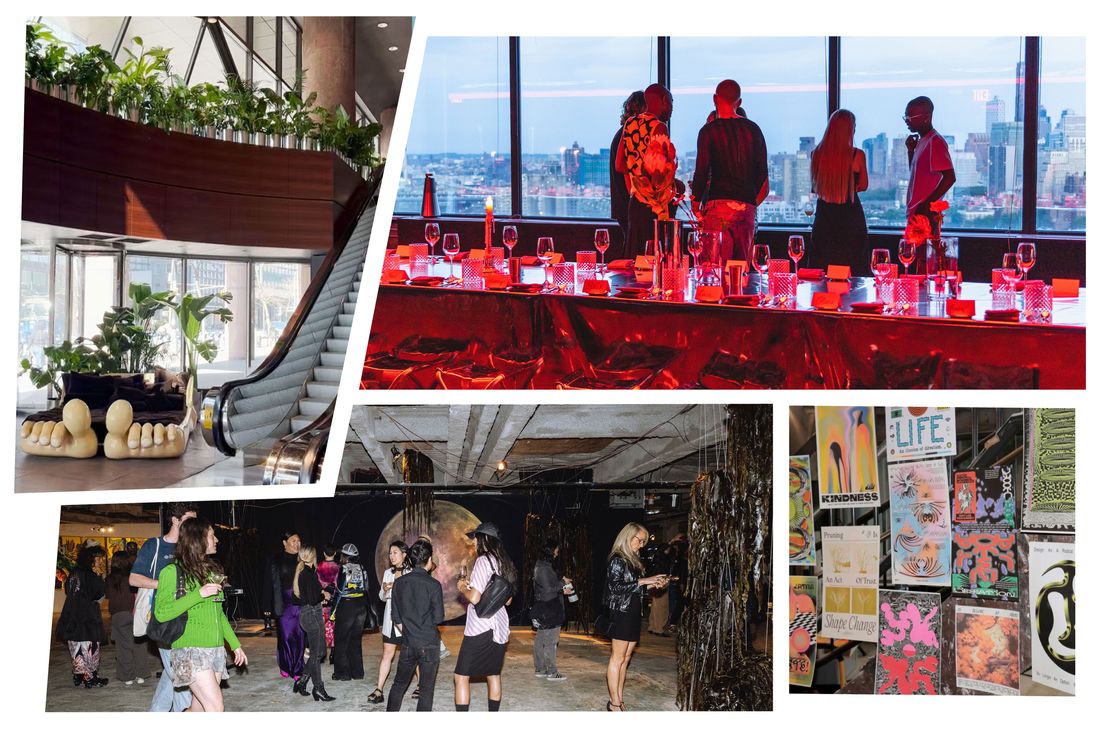

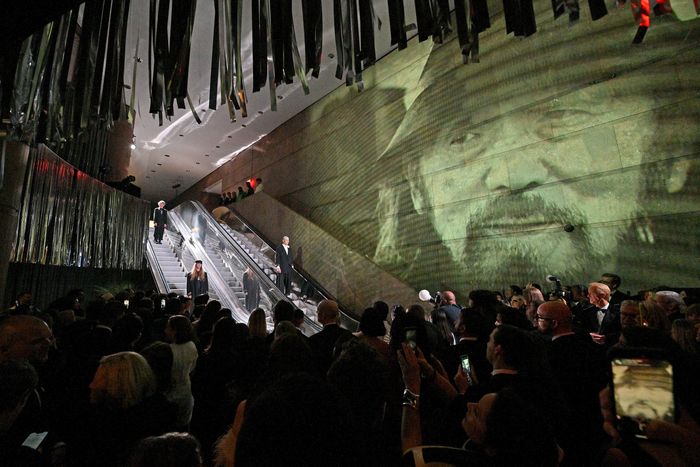

But inside, the space has been transformed into something entirely different — a place where artists schmooze with editors and curators, then stop for elevator selfies. This kind of cultivated scene hidden behind a banal exterior has become the trademark of the Khalils, who run the space and have been expanding their footprint across the city lately — with Happier, an Erewhon-ish grocery store on Canal Street, and 154 Scott Avenue, an industrial warehouse that holds the popular-on-TikTok restaurant Habibi and has hosted fashion shows that drew Beyoncé. Before opening this spring, 161 began hosting events, kicking off with Emily Ratajkowski’s après-Met party thrown by KMJR last May. (The event planner became tenant No. 1 in a set of downstairs offices.)

What’s drawing small boutique businesses to rent here isn’t just the clout — it’s a total reimagining of the modern office, a plan for layouts, event spaces, and amenities that has also convinced the city to hand the building a tax break. “This is not a ‘Let me gussy up the lobby,’” kind of project, said Melissa Román Burch, the COO of the New York Economic Development Corporation. “This is a transformative renovation.” The hope is that the tax break will allow the developers to draw what they’re calling FACT tenants (fashion, arts, creative, and technology) to a building whose giant floor plates were designed to lure FIRE tenants (finance, insurance, real estate, and legal).

On a tour with the building’s chief of special projects, Sam Wessner (who also oversees Palm Heights), I saw a handful of the floors that have been refurbished or are about to be completed, with workers scurrying in and out from behind plastic sheeting. The interiors were overseen by Gabriella Khalil, who holds the title of creative director. She played into the building’s 1980s bones, giving the place a villainous American Psycho vibe that’s undercut with a dose of humor. Instead of stuffing plants into odd corners, Khalil grouped more than a hundred in reflective chrome planters that stretch around the lobby’s curving glass window to create a cross between a lush jungle and a Yayoi Kusama mirror room. Just below them, commanding the lobby, is a hokey full-size bed in a frame designed by Frank Oelke that looks like two human feet with bulbous upturned toes. In a commissary at the top of an escalator, an original cabinet by Memphis Group founder Ettore Sottsass holds branded WSA merch.

Recently, several artists have moved into a row of studio spaces on the seventh floor, all furnished with industrial sinks. They include Eric N. Mack, a textile artist who has shown with Hauser & Wirth; Jeffrey Meris, who came from a residency at the Studio Museum in Harlem; and Johnson, a painter of moody work who moved from a warehouse in Flushing that he found “very solitary.” Johnson said he has met the other artists while working out of the space; upstairs are tenants who could help these artists get attention. (Reported neighbors include: V Magazine, Cultured, Office Magazine, and Elephant, which threw a party in the offices last year that drew the designer Telfar Clemens and the artist Mickalene Thomas.)

Only a few months in, getting an office here requires joining a wait list, and the tenants who are already here seem to have known the Khalils for years. Raul Lopez, the designer behind the label Luar, was stuck at Palm Heights for months during a COVID lockdown; he has an office upstairs. The team behind Ghetto Gastro, a Bronx-based food collective, was there for the lockdown too and now runs the lobby commissary. Tillies, the Palm Heights hotel restaurant, runs a catering service for 161’s events, including a Free Arts NYC gala. Everyone in the know may be getting a deal. Tenants I spoke to said they are paying market rate, but in their application filed with the city, the developers described how “attractive starting rents as low as $12/SF would be aligned with creative tenant budgets and offered to the right small businesses. As tenant budgets grow, rents will grow,” an approach they describe in that application as “landlord as incubator.” “If you actually understand culture and the relationships they have and how the people who go to the resort are all aligned,” said Kevin McIntosh Jr., the planner who threw Ratajkowski’s Met Ball after-party, “it all kind of makes sense.” In the lobby, he has run into fashion photographers and Vogue editors — the kind of people who book him. This week, he recognized the GQ editor Miles Pope. Last week, the building’s Instagram featured pictures of Erykah Badu at an event and an elevator selfie by Stephanie Ketty, the vice-president of business development for BFA. “There’s always someone in the building,” McIntosh said.

Despite the project’s massive scale, everything that’s in development, and the Khalils’ involvement, it’s not clear if the couple actually owns the building. Or who does own it. Or who owns Palm Heights, 154 Scott, or that grocery store, for that matter. Nor is it clear how the Khalils came to run any of these spaces in the first place. But the people who are drawn inside don’t seem to care, even as the Khalils seem to be rapidly developing across New York. In a rare interview with Bustle last month, Gabriella Khalil gave a glimpse into how she might have gotten into real estate: She was a Sotheby’s Institute grad who was working in art galleries in London when she met her husband. He asked her to help stage homes to assist with his business, and they shifted to working on a hotel because of an “opportunity that came up,” she said.

That opportunity seems to have come from Ken Dart, a reclusive billionaire who profited off the Greek financial crisis and has more recently been making contrarian investments in big tobacco. On its website, Dart’s company, Dart Enterprises, describes how it helped flip the Hyatt that would eventually become Palm Heights. Local news reports claim Dart still owns it, but the PR firm representing the Khalils says they do. (Dart did not return a request for comment.) According to The Real Deal, Dart was also in talks to buy 175 Water Street before reportedly withdrawing over the negative publicity. Instead, the building sold to an LLC. (The PR rep for the building said Dart isn’t involved.) In documents filed with the city, Matthew Khalil, lead of the property-development company Khalil & Kane, is listed as one of two principals. The other is Dawson Stellberger of developer Bushwack Capital, who is also partnering with the Khalils at 154 Scott Avenue.

Whoever does officially own it, the space will continue to grow over the next year. A cafeteria, photo studio, recording studio, screening room, test kitchen, a place to film in XR, and a lounge with a bar are all slated to open. There are already conference rooms for client meetings and event spaces to host readings or galas. The tax-break application outlines future plans to turn the third and fourth floors into a kind of Dover Street Market where brands with offices upstairs can sell what they make or source — like the vintage finds of Marcus Allen, the archivist of ’90s and aughts streetwear who runs the Society Archive and has reportedly moved onto the 19th floor. Above that future department store are two floors of museum-class exhibition space overlooking the river. In some spots, ceilings have been ripped out to create double-height rooms worthy of monumental sculptures. The tax-break application outlines plans to open the amenities to outsiders who won’t necessarily rent office space but may want in on the perks: a planned gym and a spa with two indoor-outdoor pools will be accessible to “individuals who purchase memberships.”

For now, at least, the Khalils have created something that doesn’t really exist anywhere else in the city: an office so effortlessly cool it’s turning prospective tenants away. “To me, what really creates a place is the people,” said Simon Rasmussen, the editor-in-chief of Office Magazine. “You can fill a space up with gold and diamonds, but if it’s not the right people, it won’t have the right vibe.”