If the desire to redesign our environments — from our streets to our homes — became a full-fledged obsession over the past few years, it’s exciting to consider what might come next. Below are nine new design books out this spring that continue this thread, from monographs of giants in the field, like Milton Glaser and Danish designer Jens Quistgaard, to a survey of early weed ads, to a critical analysis of one of the most consequential yet vexing elements of urban America, parking.

All titles are listed by U.S. publishing date, with the newest releases first.

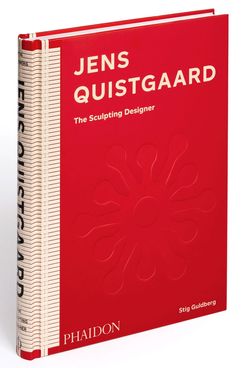

Jens Quistgaard might not be a household name, but his work, namely for the brand Dansk, makes up among the most recognizable Scandinavian-inspired designs in the United States. His reissued Kobenstyle cookware continues to sell well on Food52, and his teak pepper mills routinely sell for hundreds of dollars on eBay and 1stDibs. Quistgaard was an artist first, driven by the joy of creating things and a love of form, and this new monograph about him, Jens Quistgaard: The Sculpting Designer, offers an encyclopedic look at his body of work, from the animal figurines he made when he was 5 years old to a teak barstool he designed at age 83, along with all of his work for Dansk, of course. The book is a design object in and of itself, with a textured spine inspired by the woven rattan handles he often used on his ceramic teapots and Kobenstyle cookware. —Diana Budds

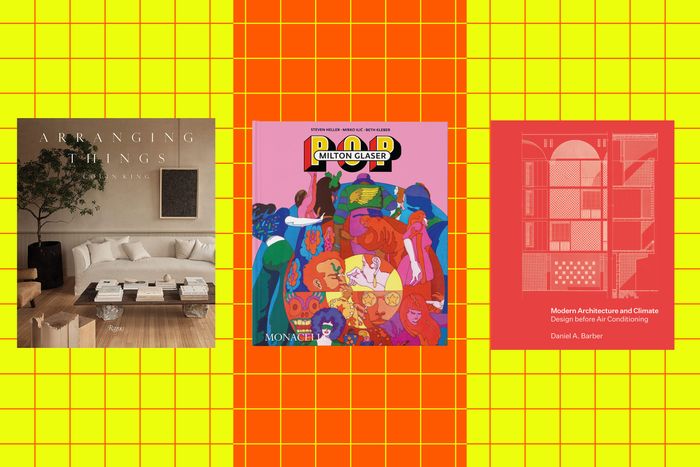

The work of a stylist is really making art out of relationships — between shapes, textures, materials, and colors — in a way that’s satisfying to see. In just a few years, Colin King has become a stylist who continues to surprise us with his instincts, styling minimalist yet still visually rich interiors for clients like Roman and Williams Guild, Architectural Digest, and Anthropologie. Despite working with big brands, King’s approach is remarkably accessible and sustainable, and his book is a guide to looking at your own belongings with a fresh perspective. —D.B.

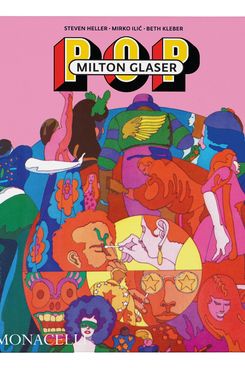

We don’t need to remind anyone on this particular website of the design greatness of Milton Glaser. He co-founded New York Magazine, created and co-wrote the “Underground Gourmet” column, and drew the logo at the top of this page as well as another familiar logo with the same initials. His worldview continues to infuse every story we publish, both print and digital. But all the design accolades only begin to touch his work as an illustrator and artist. Starting with Push Pin studios in the early 1950s, he was incredibly prolific, working steadily almost right up to his death two years ago. Book covers, LP jackets, posters, promotional pieces, and labels for canned goods flowed from his multicolored pencils and pens and brushes. (And only pencils and pens and brushes: “My hands have literally never touched a keyboard,” he said late in life.) Milton Glaser: Pop collects hundreds of his illustrated pieces and usefully funnels them into broad categories: “Silhouettes and Shadows,” “Outlines and Strokes,” “Rays and Rainbows.” That structure clarifies that he had a few go-to devices that he relied upon often and consistently, but it also reveals just how much you can do with a basic idea once you get good at it. And Glaser was very, very good at it. —Christopher Bonanos

Technology had a profound effect on the architecture of the 20th century. Skyscrapers wouldn’t be possible without elevators, and buildings with massive footprints are only possible because of artificial lighting and mechanical heating and cooling to bring light and air deep into these monoliths. We now know of the tremendous environmental consequences of this type of construction: Buildings account for 40 percent of energy use and a third of greenhouse gas emissions. But not all modernists were so keen on making their architecture machine dependent, as historian Daniel Barber illustrates in his book, which is new in paperback. He examines well-known projects by Le Corbusier, Richard Neutra, and Luis Barragan and movements like Brazilian modernism, surfacing how they responded to climate and environment, and traces how these architects’ interest in making ecologically healthy buildings succumbed to the demands of the heating and cooling industry. It’s a rare opportunity to look closer at modernists’ environmental ethics and not just their aesthetics — and a timely reference for our worsening climate crisis. —D.B.

While he’s known for his boxy sculptures, Donald Judd’s true medium was space. He conceived of total environments, meticulously designing furniture, dinnerware, and even the interior of his Land Rover to his exact specifications (and minimalist aesthetic, of course). The way he arranged his spaces was so important to him that one of the requests in his will was to preserve everything in his homes and studios exactly as he left them. These are documented in an expanded edition of Donald Judd Spaces, which includes newly commissioned photographs and archival images of his Soho loft and his buildings and landscapes around Marfa, Texas. —D.B.

Today’s cannabis rush owes a great debt to the Underground Press Syndicate, a group of radical newspapers that started in the 1960s and took on the legalization of weed as a pet project, among other countercultural concerns. The ads, illustrations, comics, political cartoons, and more that ran in these papers — like the East Village Other, The Los Angeles Free Press, and the Berkeley Barb — were among the first entries into the stonercore art canon. While each paper had its own editorial direction, the same articles about cannabis appeared in multiple publications. Heads Together: Weed and the Underground Press Syndicate, 1965–1973 gathers this ephemera along with essays and oral histories about publishing in the era from Ishmael Reed, John Sinclair, and Marjorie Hines. —D.B.

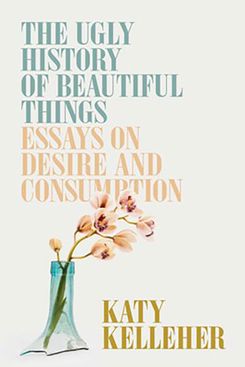

There’s no shortage of status objects in our culture today: rare gemstones, whisper-thin porcelain, and gleaming marble countertops, to name a few. But if you take a step back, you have to wonder why these things command so much desire. How, exactly, did the glandular secretions from a male deer — that would be the musk aroma used in perfumes — become a symbol of luxury? The Ugly History of Beautiful Things looks closer at these compelling objects through deeply fascinating essays that braid together anthropology, art history, psychology, and the author’s personal relationships with aspirational objects. As the book’s title alludes, there’s a sinister backstory to the items Kelleher analyzes — it’s usually some combination of hazardous production methods and environmental degradation — which speaks to an ongoing backlash against consumerism and rapid trend cycles. But it’s not all doom and horror; Kelleher’s message is ultimately a hopeful one: There is plenty of pleasure to be had by honing your eye to see an object of beauty instead of rushing to own it. —D.B.

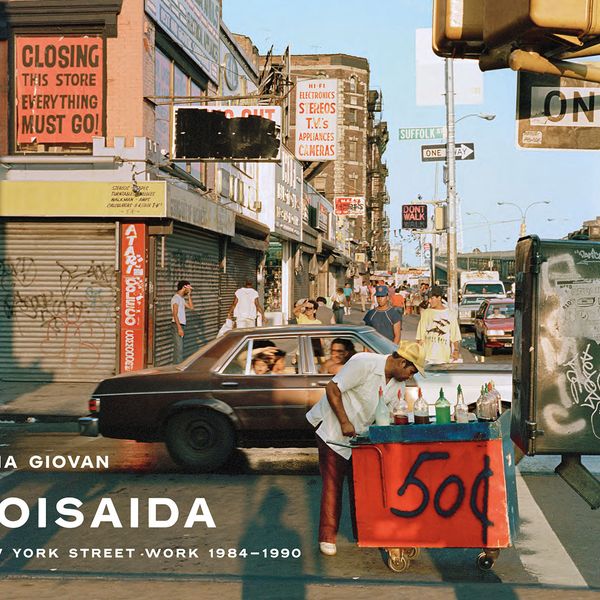

While Tria Giovan lived on the Lower East Side, between 1984 and 1990, she took hundreds of photographs of her neighborhood. But it wasn’t until the pandemic that she actually pulled out her negatives and edited the images. The result is a gorgeous new photo book of the neighborhood from a time before Starbucks, Shake Shack, and million-dollar condos. Giovan’s images of pastel apartment buildings, storefronts with hand-painted signs, and a boxing ring set up in an intersection feel surreal, even idyllic, compared to the gritty photographs that we often see of New York during that time period. —D.B.

Paved Paradise, by Slate columnist Henry Grabar, investigates a topic that’s somehow simultaneously mundane and radicalizing: our extremely American, almost existential search for a parking spot. Where we can park, for how long, and at what cost explains pretty much everything in our car-dominated society, from the type of housing we build to the way our climate is changing. Grabar serves as a tour guide to the seemingly innocuous policies that entrench parking as a right rather than a service, like free overnight parking (a surprisingly new innovation!) to the utter hopelessness of the municipal math that plops a vast asphalt lot in front of every big-box store. Seeing the country through a “parking rules everything around me” lens is an eye-opening education on how tiny land-use tweaks can engineer true social transformation — and how powerful forces will stop at nothing to prevent those spaces from being used for literally anything other than car storage. —Alissa Walker