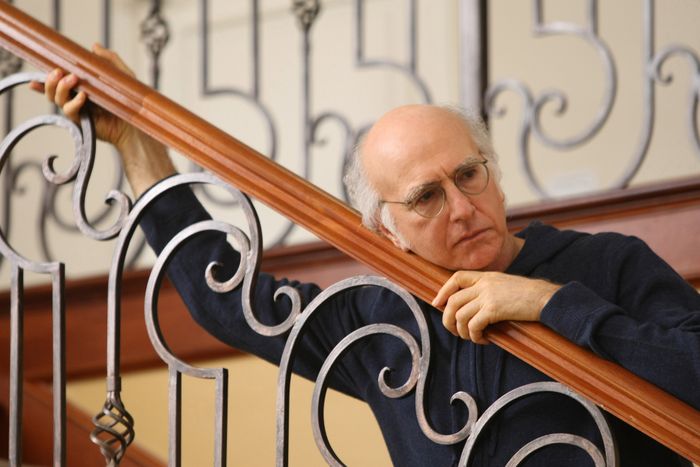

Larry David moves a few times on Curb Your Enthusiasm, but his houses tend to look the same: big iron staircases, oversize doors like an entrance to a villa, brocade upholstery and drapes. Beige, brass, gold. The style is derivative of so many others — an amalgamation that has no country of origin and is of no particular era, but is nonetheless legible to anyone who grew up in Los Angeles in the years between 1995 and 2007 as one thing: new money.

In its 12-season run, Curb takes place almost exclusively on the city’s West Side: Santa Monica, Brentwood, the Pacific Palisades, and Beverly Hills. The homes and locations are generally variations of a type: leafy Italianate, Spanish Colonial, or Normandy-style mansions. The interiors are over the top, which is not to say they are unbelievable. I’ve been in these houses, sitting at the kitchen islands of the rich girls I went to middle school with, surrounded by marble counters and faux-rustic kitchenware because their mothers had watched Under the Tuscan Sun. Huge candles, oversize coffee-table books (like Larry’s ill-fated gift to Ted Danson, Mondo Freaks), bowls of fake fruit or potpourri adorn pre-distressed wooden tables. This was before a restrained and minimal aesthetic took over the city — in Kim Kardashian’s 2007 episode of MTV Cribs, her house doesn’t look so different from Larry’s — and something at once gaudy and bland defined the tastes of Larry’s milieu: The new millennium’s freshly minted millionaires, not yet familiar with the Axel Vervoordt interior flex, adored conspicuous beige.

David Saenz de Maturana, production designer on the show’s last four seasons, says the interiors were meant to be real but exaggerated — an extension of what Curb does with everything it touches. “It was somewhat loosely based on Larry’s personal preference of architectural aesthetic, but a kind of more a hyperreal version of himself.” (A quick search of the Seinfeld creator’s past homes bears this out.) There were also small touches meant to personalize the spaces, like a photo from David’s bar mitzvah displayed in his study. “He always wanted it to be real, making the set look like real life in order to show his world,” says de Maturana. And for Larry and Cheryl, and later Larry and Leon, that world is large clocks in the bedroom. Big chenille pillows with fringe trim adorning their oversize couch and bed. Candelabras, drapes, and decorative objects, all evoking something vaguely Italian. Nothing looks very expensive, just intentionally overpriced — throwing the Amex down at Cost Plus World Market, objects and furniture to fill an excessively large house with too many rooms to use.

There were, of course, deviations from the norm: Richard Lewis lives in more of an ’80s bachelor pad with black marble countertops, black leather couches, and a sleek fireplace. Jeff and Susie also move a few times, from a modernist box to a house with a kitchen that oozes HGTV-inflected farmhouse — a home an agent would live in as a custodian of the industry but not its star. Of Susie Greene, de Maturana says, “We took her tone, and it just kind of pushed that step further. We tried to think of who Susie Greene would be working with, in terms of an interior designer, and what kind of spaces they would sell her on and what kind things that she would find appealing and attractive to match her or outrageous wardrobe collection.” (In later seasons, Susie gets into millennial pastels. A rose-gold tic-tac-toe board sits on her coffee table.)

Los Angeles is vast, but Larry’s experience of it is not. The sets run on a sort of loop: In semi-retirement, he golfs, goes to lunch, idles at home, idles at Jeff and Susie’s. The style is particularly Los Angeles in its mash-up of different cultures and eras, rendered bland and indistinct through the superficial interpretations Larry encounters. (I think of Woody Allen’s line in Annie Hall during the L.A. visit: “The architecture’s really consistent, isn’t it? French next to Spanish, next to Tudor, next to Japanese.”)

The bland grandeur of the interiors somehow accentuates the absurdity of Larry’s life of complaints. In a polo shirt and cotton blazer, he stands in front of an elaborate gold mirror, his casualness bluntly contrasted with what looks like a cheap version of something belonging to Louis IV. (Here, he claims to have found the perfect sock.) The settings and Larry’s incongruous relationship to them adds to the humor — a middle-class Jew from Brooklyn now in Beverly Hills with a blonde goyishe wife in a McMansion. The bad taste is almost the point.