The morning of May 30, 1995, dawned cloudy and mild in New York City. All around the Lower East Side, cyclists rode with walkie-talkies and spotters stood on rooftops. Overhead, helicopters hovered. Inside an apartment building at 541 East 13th Street, a group of residents waited behind doors that they’d welded shut. Soon they got word: The NYPD was converging, and it had a tank. A flood of riot-squad officers advanced on the buildings while protesters linked arms. On the roof, the guy with the piss bucket waited patiently.

This row of buildings on East 13th between Avenues A and B had been abandoned, then taken over by the city, in the 1970s — just like hundreds of other rotted-out or burned-out shells across the Lower East Side. In early 1984, a cabdriver was killed in 539, and the police response briefly drove out the drug dealers who had taken it over. That week, a handful of idealistic community organizers moved in, asserting ownership as squatters. Marisa DeDominicis, then a 22-year-old bike messenger, was the first. “I don’t know if I was just too stupid to be afraid,” DeDominicis said in a recent interview. “I was just really interested in what I could be part of, and ready to put in a lot of energy to make it happen.”

To secure residence, the activists installed a front door where there had been none. “It took all day,” the longtime resident Rolando Politi said in a 2010 oral-history interview. “Who has got the wood, let’s go around, have to find the piece of plywood. Then we took coffee breaks.” By the evening, he recalled, “people brought beer, drinks, singing, people came with guitars. By a little before midnight, the lock was on.”

Much of my new novel, Vintage Contemporaries, is set in a squat not unlike the 13th Street squats that grew around that initial building and its hard-won new door. From the late 1970s through the 1990s, dozens of abandoned New York buildings were taken over by city residents in need of housing. The movement’s center was the Lower East Side, where punks, DIYers, community activists, parents, and others reclaimed the ruins. The buildings frequently started as burned-out shells, the remnants of landlords’ attempts to collect insurance money before ceding the buildings to a state of nature (and city ownership, once the taxes went unpaid). Some mostly stayed that way, serving essentially as roofed campsites for an ever-shifting cast of hard-living young people.

But many of the squats, including the ones on 13th Street, were made livable, even desirable, through years of sweat equity. Often self-taught, squat owners repaired roofs, jackhammered bricked-over windows back open and installed double-paned glass, wired and plumbed their hardscrabble homes. In one squat, residents replaced all the rotting joists in their building, using materials lifted from construction sites. (They traded the workers cold beer in exchange.) In 1988, DeDominicis, expecting her first child — she eventually raised three on 13th Street — installed her own heating system. “I had a boiler in the area that had been the elevator,” she told me, “and I ran pipe in the apartment, with slant-fin radiators.” Many of these residents spent years petitioning the city to recognize their work and grant them ownership. “We installed an electric meter,” DeDominicis said. “We wanted to be legitimate. We wanted the city to recognize what we were building there.”

For a time, New York looked tolerantly upon the squats, even granting some homesteaders title to their buildings. “If the tenants were organized enough, the city would let them take it over with a nominal payment and some legal structure,” said the author and historian Lucy Sante, who lived around the corner from the 13th Street squats for years. “Before the market started getting excited in the early ’80s, the city didn’t care. But when the market started jumping, they just abandoned everybody.”

By the 1990s, squat residents across the city were facing eviction, with the city using code violations and vacate orders to clear the buildings at any opportunity. Squatters created eviction phone trees so that activists could descend on a building in minutes if a resident was getting hassled by the authorities. “For at least a year or so, we had been protesting and fighting,” said Ash Thayer, a photographer who lived in See Skwat, on Avenue C between 9th and 10th. “Going to eviction watch meetings, community board meetings.”

A number of residents of the 13th Street buildings challenged a vacate order in court, claiming that New York’s adverse-possession law allowed them to claim title to the buildings. In April 1995, a sympathetic judge blocked the city’s eviction efforts, a decision the city appealed. An appellate panel couldn’t hear the case until September but refused to prevent evictions in buildings the city declared in imminent danger. It took just days for the police to move in.

Sarah Ferguson, a journalist who’s reported on the struggle for housing for years, covered the May 30 police action for the Village Voice. “It had a celebratory air,” she recalled. “Someone tipped over a car and set it on fire to block the street.” (In photos, the car, a white sedan, has been heavily tagged: ECONOMY DECLINE, it reads.) “People came, Warriors-style, to battle, on Rollerblades, with trash can lids.”

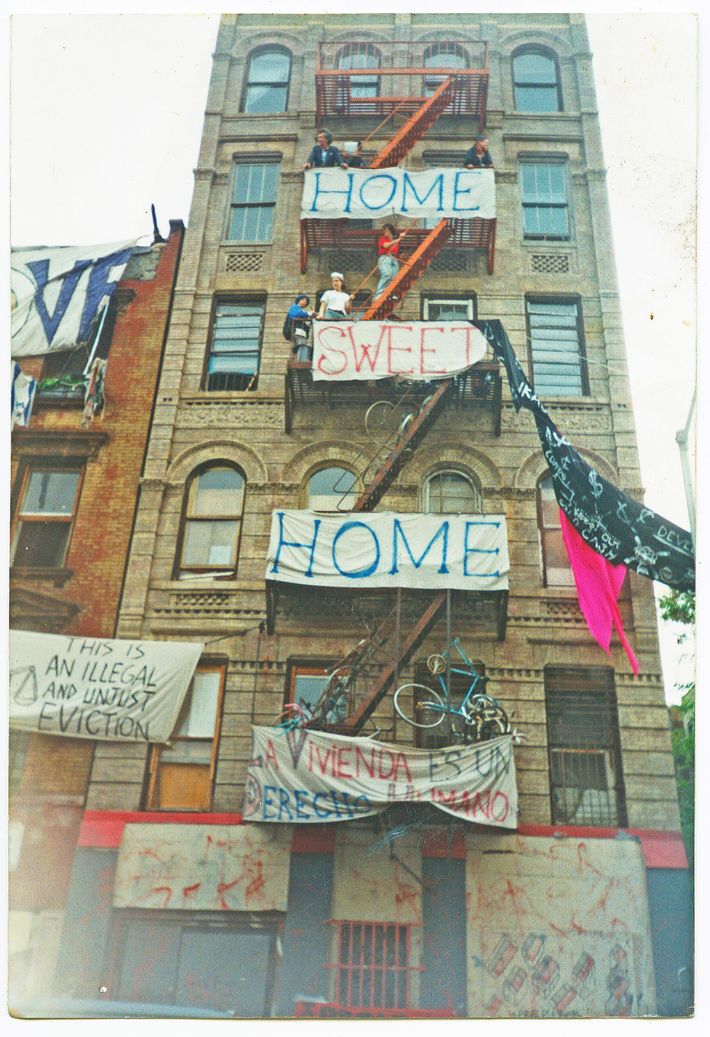

Banners hung from the balconies: HOME SWEET HOME. THIS IS AN ILLEGAL AND UNJUST EVICTION. They hung unevenly because underneath them, residents had welded bikes to the railings to prevent police ladders from gaining purchase. DeDominicis watched from across the street with her children. “There were so many cops in riot gear,” she said. “Waves and waves.” The protesters spread wet roofing cement all over the sidewalks and linked arms. Then they watched as the tank, an enormous armored vehicle on treads emblazoned with the NYPD logo, rolled down 13th Street.

Ferguson was inside the building, where the last holdouts had welded themselves behind the front door. “Is this real?” she remembered asking herself. “It’s like Apocalypse Now. There’s a fucking tank! It was a big Giuliani shitshow.” As the cops cracked down on the protesters in front of the building, shoving them to the ground while dodging urine poured from the roof, the squatters inside snuck out through the back and dispersed into the surrounding yards. On the roof, a squatter everyone called Cheese performed a Nazi salute to the cops. Shouting at them from 40 feet up, he goose-stepped along the parapet.

That was the photo that appeared on the front page of the New York Times the next day. “With a show of force befitting a small invasion,” the story began, “the Police Department seized two East Village tenements yesterday, overwhelming a defiant group of squatters who had resisted city efforts to retake the buildings for nearly nine months.” Police arrested 31 protesters. For the rest of the summer, police continued barricading 13th Street, forcing residents to show ID and be questioned to proceed onto the block. On the night of July 4, protesters snuck past police into the vacated buildings, hanging fresh banners and shooting fireworks off the fire escapes. As chronicled by the artist Seth Tobocman in his graphic novel War in the Neighborhood, by the time the police flooded the building, the squatters had vanished. The only voice they heard was a boom box playing Bob Marley’s “Get Up, Stand Up.”

I lived on the Lower East Side in the summer of 1994, a clueless college sophomore taking film classes at NYU. I had no idea of what was playing out all around me: the recent battles for Tompkins Square Park, the fight for fair housing. Like many 20-year-olds, I was wearing blinders, concerned only with the vaguely defined professional future that I believed lay ahead of me.

Twenty-five years later, writing my first novel, set in New York in the 1990s, I didn’t want my heroine, Em, to be as clueless as I was. Or, rather, I wanted her to start that way, but come to experience and understand just a little of the cultural and political ferment of her time and place in a way I never had. I put Em’s best friend, a rabble-rouser named Emily, in a fictional version of a Lower East Side squat, and let Em, a sheltered Wisconsin girl, come to love this place and the struggle it represented.

Since most of what I knew about the squats came from, uh, Rent, I read everything I could about these homes and the people within them, people who “were sort of rumbling and tumbling through American life,” as the 13th Street organizer Peter Spagnuolo said in his oral-history interview. Amy Starecheski conducted most of those interviews, which now live in NYU’s Tamiment Library, and her book Ours to Lose: When Squatters Became Homeowners in New York City is an invaluable account of the culture and practicalities of the Lower East Side squats, as well as a powerful delineation of the moral, legal, and philosophical debates around legalization. From Ash Thayer’s book of photographs Kill City, I got a sense of what those spaces really looked like, with their raw brick walls, DIY appliances, and lovely, homey touches. In one photo, a young woman sits in front of a TV, watching what I’m almost positive is The Fresh Prince of Bel-Air, holding a mug of coffee. Over her head, an intricate homemade mobile hangs from the ceiling. Beside her, in a scavenged antique chair, sits a beautiful black cat.

It became clear to me, as I wrote, that an eviction not unlike the one in May 1995 could serve as a climax to the 1990s section of the novel, serving both to cement Em’s political beliefs and to divide her from Emily, who comes to find the endless legal and activist struggle exhausting. Writing that section in the summer of 2020, as I took to the streets with my kids and my neighbors in the Black Lives Matter protests, made the idea of illuminating this tiny corner of New York history — the time the cops drove a tank into the Lower East Side — seem even more crucial.

And in the end, setting a significant part of this book in the liminal space of the squat — a home but a wreck, a community but also a group of rough-hewn individuals — helped illuminate how liminal our 20s can feel. It’s a time when we’re becoming someone, fiercely and determinedly, even if from the distance of decades we don’t quite recognize who it was we were so set on becoming. The second half of the novel is set years later, as Em reconnects with Emily, and the memory of the uncountable hours the two women spent in that squat — listening to music and drinking beer out of a mini-fridge called the State of Denmark (because something’s rotten in it) and talking, talking, forever talking — becomes a kind of faraway place Em and Emily are trying to recall, even, if possible, revisit.

The evicted squats on 13th Street were immediately gutted and renovated into low-income apartments, and they remain so today, not that different from other apartments in the Lower East Side. “The absurdity,” Sarah Ferguson said. “The city was kicking everybody out to let some other group renovate it for housing. You used to have a city homesteading program! And then just when property values start rising, the city decides that homesteading is no longer useful.”

But the chaos of May 30, 1995, was a turning point for the squatters of the Lower East Side, Amy Starecheski told me when I interviewed her. “It really changed the public perception of what the balance of power was,” she said. “It showed how much force the city was willing to use to evict squatters.” A few days after the tank rolled, Lucy Sante wrote an impassioned defense of urban homesteading in the Times. “In destroying the squats,” she wrote, “New York is destroying homes, punishing initiative, undoing community improvement, criminalizing hard work, squelching ambition and killing hope and serenity. In other words, it is attacking itself.”

“If we make them roll hundreds of cops and spend millions of dollars,” Peter Spagnuolo told Starecheski, explaining why 13th Street fought, “that means these other buildings might make it.” The city, he thought, would eventually have to concede: “You can’t have these violent spectacles of removing people who have done all this work on these abandoned buildings.” He was right. Faced with the possibility of needing to repeat this kind of action over and over — and still trying to work out the ramifications of the lawsuit, which, though it didn’t save most of the squats on 13th Street, did establish that squatters have an adverse possession case — the city blinked. The result: In the 2000s, the city sold 11 Lower East Side squats, including the single remaining one on 13th, to the Urban Homesteading Assistance Board for $1 each, and the buildings became co-ops, with former squatters assuming the debt incurred for renovations to bring the buildings up to code.

It’s a complicated story, one that continues even now. “Some see legalization as an unprecedented victory, others as a stinging defeat,” Starecheski writes in Ours to Lose. Securing financing for these debts was a difficult and sometimes impossible process. Many squatters had been paying little in rent or fees or real-estate taxes; trading that for a situation in which they had to pay off loans, putting them at risk for eviction, was worrisome. “There really is no graceful way to translate anarchy into some form of social capitalism,” squatter Jessica Hall told Starecheski. “It was gonna hurt.”

When her children were little, Hall snuck into a squat on East 7th Street with them; years later, she owns her apartment there. For her, the opportunity to be a homeowner, which might never have happened without the resistance protesters put up one May morning in 1995, has transformed her life. She could stay home with her kids; later, she could go back to school to study social work. “I’m fucking delighted, you know?” she said. “It’s just been an amazing, amazing thing. I’m the luckiest person in the world.”