The Jewish Museum’s “Frederick Kiesler: Vision Machine” is a tiny show about a tiny man with huge ideas that he rarely put into practice. He belonged to a generation of dogged builders, ideologues, and opportunists who transformed cities around the world: men like Mies van der Rohe, Le Corbusier, and Walter Gropius. Unlike them, Kiesler spent years laboring over practical impossibilities that looked promising only decades after his death in 1965. With his Mobile Home Library, which the exhibition re-creates in a new life-size fiberglass model, he tackled the question of how to make vast stores of information at once compact and instantly retrievable — a problem it ultimately took the smartphone to solve.

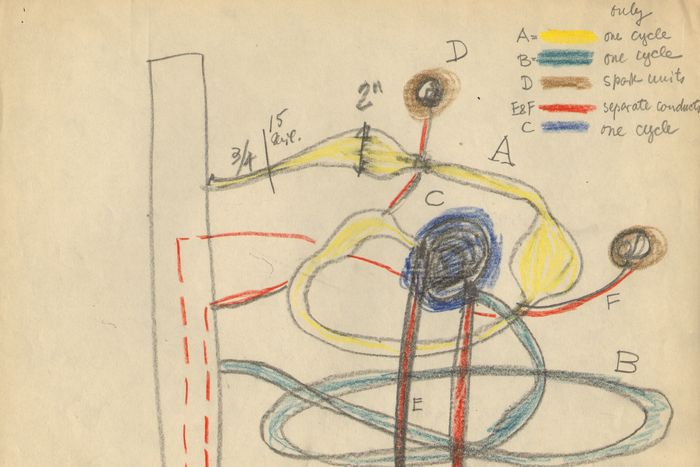

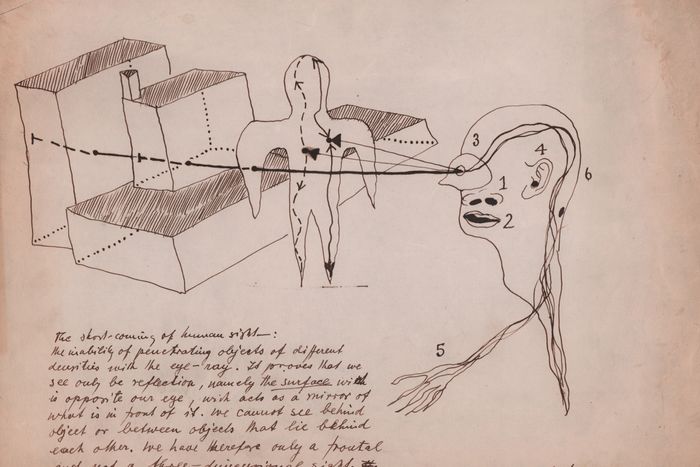

Kiesler was undeniably prescient — and that and a nickel will get you a cup of coffee, as they used to say in his day. He spent years trying to make a Vision Machine, a doomed attempt to translate the experience of sight into physical structure. It wasn’t just seeing that fascinated him but the way humans make sense of the visual world. He wanted his contraption to register, to hallucinate, perchance to dream. “The Vision Machine demonstrates, first, the flow of sight. It also portrays the origin and flow of visionary images. All parts of this machine are connected mechanically,” Kiesler explained. “From the beginning to the end, a talking apparatus gives a synchronized explanation with the unfolding of the process in demonstration.”

That characteristic mixture of the hyperpractical and the fantastical animates a show that will leave a lot of visitors puzzled — trying to read documents that float away on rotating stands or make sense of cryptic drawings that look like the jelly-bean doodles of an 8-year-old boy. Curator Mark Wasiuta evidently thinks the time has come for Kiesler’s reputation to bust out of its niche of dedicated admirers. He may be correct, but this show won’t do the trick because it leaves out so much of what made Kiesler the eccentric prophet that he was.

Kiesler thought of architecture as a fluid field capable of self-perfecting and constantly adapting to its users’ changing needs. Nature constructs through ceaseless cell division and multiplication, a process that ends only with death. Humans build by accretion — add pieces until you declare the job done. Kiesler’s formula for bridging the difference between growth and architecture was “continuous construction,” an approach that elided the separation between inside and out, membrane and structure, ceiling and walls, finished and not. His Endless House represented the apotheosis of his concept: an unbuildable, perpetually incomplete, blob-shaped cocoon on stilts that would evolve in sync with its residents’ needs. With its grass-and-pebble floors and curvy concrete exoskeleton, it could be the great-grandfather of the Gilder Center at the American Natural History Museum. Kiesler sexualized those curves, developing an aesthetic that contrasted with the rectilinear architecture of macho modernism. “It is endless like the human body,” he wrote. “There is no beginning and end to it. The ‘Endless’ is rather sensuous. More like the female body in contrast to sharp-angled male architecture.” The anatomical comparison became even more explicit in his sole still-standing creation (a collaboration with Armand Bartos), the Shrine of the Book in Jerusalem with its milky, nippled dome. The Dead Sea Scrolls lie within that great cupped chamber, its surface ribbed with circular striations like a clay vessel thrown on a giant’s wheel.

If Kiesler at mid-century was thinking about wombs and caves and curves, he was hardly alone in the architecture world. Architects in Mexico and elsewhere were exploring the appeal of mysterious passageways, soft openings, and enveloping chambers made possible by carving spaces out of the earth rather than building them up top. The dimples, folds, and limbs of Eero Saarinen’s TWA Terminal at JFK airport gave flying a sexy dimension. Kiesler’s contemporary Carlo Mollino had to wait a little longer, until 1973, to fit out Turin’s Teatro Regio with a hot-red oval auditorium that the Times’s architecture critic Herbert Muschamp once said “should probably be X-rated.” (The Jewish Museum show averts its gaze from the carnal part of Kiesler’s practice.)

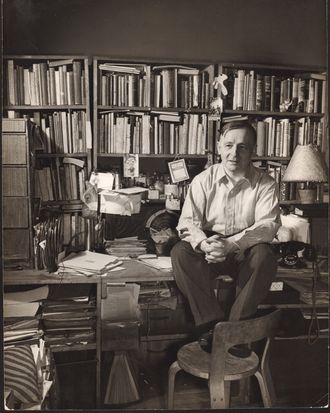

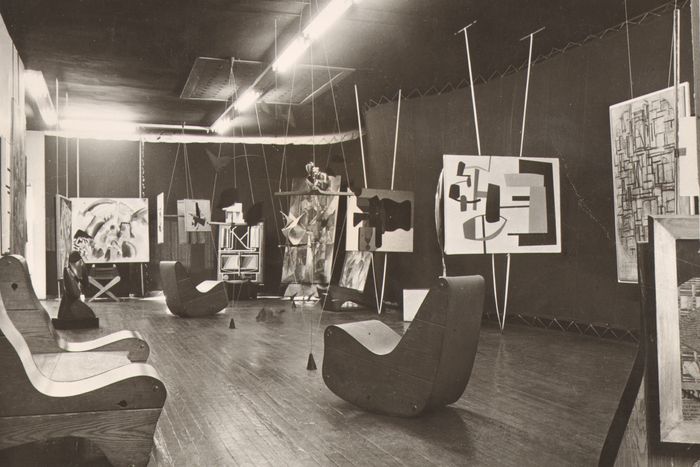

A whiff of charlatanism clings to the man Philip Johnson called “the greatest nonbuilding architect of our time.” He arrived in New York in 1926 and was quickly absorbed into its flock of brilliant weirdos, though that didn’t help him make a living. He decorated the occasional Saks window, designed the odd theater production and a small movie theater in the Village for the Film Guild, and devoted himself to modernizing Americans’ taste in art. Natty and gregarious at under five feet, he uttered insights that sounded revelatory, if sometimes incomprehensible — and not just because of his thick Middle-European accent. He dazzled his peers and puzzled all but the most open-minded clients. In 1942, Peggy Guggenheim hired him to install the exhibition space for her gallery Art of This Century, which he turned into a surrealistic trip, hanging paintings free of the walls and inviting viewers to contemplate them while bobbling comfortably in amoebalike custom rockers. “Being with Kiesler was like touching an electric wire that bore the current of contemporary history,” wrote the composer Virgil Thomson in a characteristic mix of admiration and self-regard. “Kiesler was the one among us who understood best the work that any of us was doing and who cherished it. Such faith is rare on the part of the artist who knows himself to be advanced.”

Kiesler leaned into the priestly glamour that attached itself to the word advanced. From a perch at Columbia, where he founded and ran the Laboratory for Design Correlation, he elaborated a theory of correalism, which explored the relationships between design and … everything else. The overarching principle of that vague and slippery discipline appears to be that a work of architecture ought to be responsive to who is doing what inside it. It elicited more admiration than understanding. A Teachers College administrator assured grant givers at the Carnegie Corporation that Kiesler’s “conception is so enormous that it is like describing life itself … Impossible to give a verbal idea of so much that is purely graphic.” In other words, He’s definitely doing something cosmically important, but I have no idea what that is.

Despite his theoretical airiness, the diagrams and studies at the Jewish Museum reveal a designer as obsessed with streamlining grunt work as any management consultant. In the 1918 manual Making the Office Pay, the apostle of efficiency William Henry Leffingwell recounts the hours he spent watching clerks open mail: “I noticed a lot of tiny, ineffectual motions [such as] reaching twice for pins because the pin tray had been moved a couple of inches. Speed was lost because involuntary action was thwarted. Like a flash the whole idea developed. Those pins should be in a pincushion weighted with sand and the cushion fastened to the table.” Three decades later, Kiesler studied the relationship between body and object with similarly maniacal dedication, yielding the Mobile Home Library.

In that modular, articulated structure, you can see Kiesler wrestling with the desire to keep all human knowledge within arm’s reach at all times. He was less interested in the public or institutional library than in a domestic system of storage, which he conceived of as a rotating set of linked bookshelves, each of which could spin independently. In theory, a scholar seated in the center of this miniature universe had only to extend an arm to pluck a passing tome like a fruit from the garden of wisdom. In practice, the shelving units look at once quaint and ungainly, like a set of doorless refrigerators gathered around a campfire, singing silently for an ungrateful future.

There is some irony that a man who devoted so much of his life to rethinking the ways people sit, read, think, watch, move, and interact with the material world had so little direct impact on any of those activities, at least in ordinary life. In the end, he remained a showbiz guy, a director of illusion. Perhaps the purest Kiesleresque experience you can have today is in the theater or opera house watching an open-sided structure rotate on a turntable, constantly relit and re-dressed to morph from garret to plaza, creating new settings for the characters’ shifting states of mind. That’s where architecture can truly be endless, mobile, and dynamic enough to qualify as correalist.