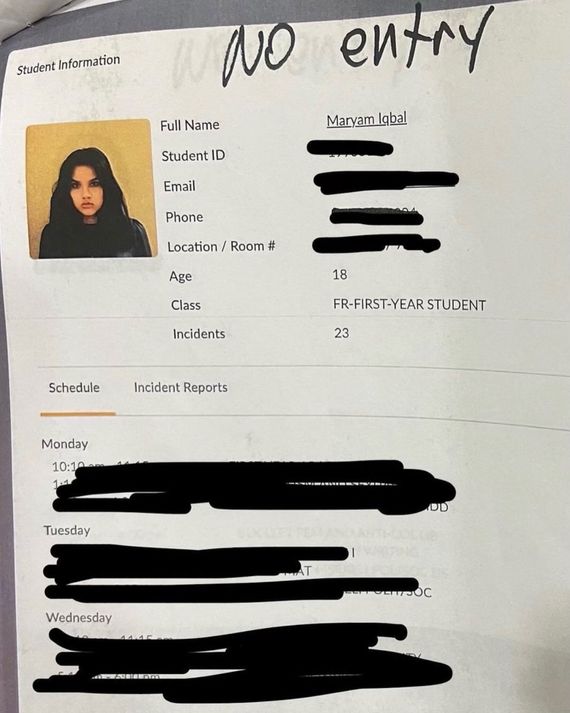

Maryam Iqbal was one of 108 students arrested on the lawn of Columbia University last week and one of 53 Barnard students who learned in an email when they got out of jail that their arrest meant they were automatically suspended and evicted from campus housing — in Iqbal’s case, a freshman-dorm room she shared with a roommate. She’s 18, on a scholarship, and her family is back in Seattle. She had 15 minutes to pack a year’s worth of books, chargers, clothes: “For some reason, I forgot all my socks.” At first, Iqbal didn’t know where to go. But she connected with other campus activists through a loose, amorphous online network of WhatsApp chains and lists of volunteers that is linking evicted students with the sofas of professors, the rooms of volunteers, and the futons of other college students.

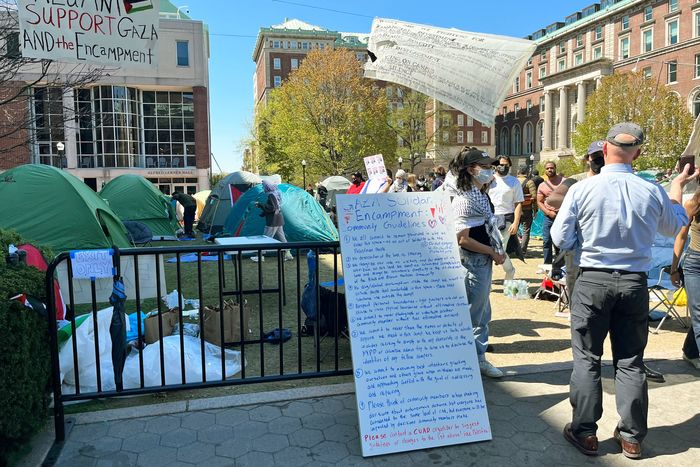

Activists started making a list of available housing earlier this month after six students were suspended on April 3 in a pro-Palestinian protest and given a single day to vacate student housing. “We had a small list of just other students’ houses where they had extra couches or a blow-up mattress,” said Catherine Elias, a 26-year-old grad student who was arrested that day and given 24 hours to abandon grad-student housing. Last week’s mass eviction overloaded the list, she said, but new volunteers quickly raised their hands: “We now have a list of over a hundred people in the community who we’ve vetted — mostly students, though a lot of faculty and staff.” Meanwhile, other students found their way back to the encampment — a collection of tents and flags spread at the foot of Columbia’s central library. “There are definitely people who are living in the camp who have to be in the camp as they have nowhere else to go,” said one activist.

Iqbal didn’t want to come back to campus right away. A photo of her face had been passed around campus-security offices. She’d been giving interviews at the campus gate, and counterprotesters had harassed her. She ended up finding a place to stay out of state and was able to get a free ticket out of town thanks to a Venmo account that had been soliciting donations.

The evictions are causing problems activists can’t solve with a WhatsApp chain and a spare couch. Bans from swiping into campus make it impossible to get to medical appointments or pick up prescriptions; one person at the camp on Tuesday cited a friend who was evicted and is now going without antidepressants. Then there’s a worry about the future. About three-quarters of Barnard students choose to live on campus in a city where renting a room can require proof of income and guarantors, but the college cites a suspension on a student’s record as a reason to deny housing in the next lottery. “Because housing is one of the most limited and coveted resources in New York City, it’s an incredibly powerful motivator to bend students to your will,” said a law student on campus Tuesday.

Barnard says it doesn’t comment on confidential student proceedings. But on Monday night, some of the evicted students were offered a form of amnesty: If they agreed not to take part in illegal activities, their punishments would be lifted and they could have access to dorms and dining halls and take classes online. But a student I spoke to said others aren’t taking the deal out of solidarity and concern that accepting the offer would force them to give up the protest.

Law student Deen Haleem said the evictions themselves at least seem to counter the university’s own rules, which give undergrads a chance to appeal their suspensions before the suspension can become the basis of an eviction, he said. Which is not a problem for Elias at the moment. “This is home right now,” she said, gesturing to the camp.