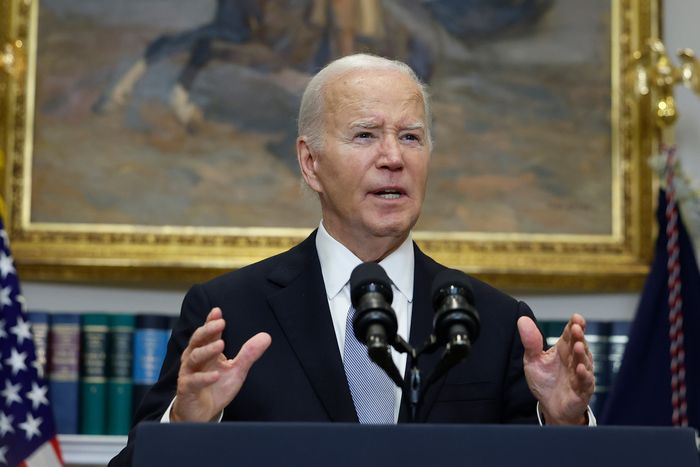

Joe Biden just dropped a proposal to cap rents at 5 percent annually — a form of national rent stabilization that, while somewhat narrow in scope (it would apply only to “corporate landlords” with over 50 rental units and last for no more than two years), reflects the growing anxiety over housing affordability that people are experiencing nationwide. The move would be a rare example of federal intervention in rental pricing, coming at a time when buying a home has become increasingly difficult for many Americans and high rents are burdening a growing number of households.

Here’s what we know.

How would it work?

The proposal, which needs congressional approval to go anywhere, would require larger landlords to either cap their rent increases at 5 percent or lose out on lucrative tax breaks based on property depreciation, with exceptions for new construction and units that are being substantially renovated. Biden made the announcement on July 16 in Nevada, where median rental prices have gone up 36 percent since the start of the pandemic. (In New York, new apartment leases have increased about 30 percent in Manhattan and 20 percent in Brooklyn.)

What kind of an impact would it have?

The rent cap would apply to about 20 million units, per the White House, about half of all rentals. (New York City’s rent-stabilization laws also apply to about half of all apartments in the city.) It is not currently paired with any good cause measure, however — protecting tenants in good standing from being booted at the end of their lease — so it would likely have to be tied to the units themselves, without vacancy deregulation, to keep landlords from simply turning over units for higher rents.

A record 22.4 million households now spend 30 percent or more of their income on rent, according to a report from the Joint Center for Housing Studies at Harvard. The New York Times has claimed that Biden regularly asks his aides for updates on mortgage rates. And despite falling inflation — 4.5 percent in 2023, down from 8.4 percent in 2022 — housing prices are up 5.2 percent annually, according to CNN. It seems that after widespread concerns over his age and ability to serve four more years, as well as the Trump assassination attempt, the president is trying to refocus the national attention on economic issues and concrete policy proposals.

How did things get so bad in the housing market?

After the pandemic, both home sale and rental prices shot up, and while many predicted that home prices would fall after interest rates rose to the highest levels in decades — they’re now around 7 percent — they have remained stubbornly high, keeping more would-be homeowners in the rental market and propping up rents. Experts largely agree, however, that the root cause of the issue is the housing shortage: Estimates place the number of units needed to meet demand between 1.5 million and 5.5 million.

Is this actually going anywhere?

Any attempt to limit rents is likely to receive major pushback — passing good-cause eviction in New York, despite significant popular support and widespread frustration over double-digit rent increases, was a yearslong battle that resulted in a weak law with relatively modest protections for renters that cities and towns have to opt into. And critics argue that limiting what landlords can charge will backfire, disincentivizing developers from building new rental housing and leading to even more shortages and competition for existing units.

What will Congress think about this?

As the Times has reported, it’s unlikely Congress will pass controversial legislation shortly before the election, which has led some political observers to view the proposal as little more than a campaign ploy. The Washington Post also reported that even if the proposal does pass, it would be short-term — a two-year stopgap until the 1.6 million units of housing currently under construction come on the market. That might make it more palatable, but it’s doubtful that the need for basic rental protections and caps will fade after two years, even as more housing units become available. About 65 percent of U.S. households live in homes they own, according to the U.S. Census Bureau. That leaves almost everyone else at the mercy of their landlords, unsure if they’ll be able to stay every year — and what it will cost them if they do — when their lease comes up for renewal.