If home is a feeling, production designer Kevin Thompson has built a career out of manufacturing that feeling. For Hagai Levi’s Scenes From a Marriage, the series adapted from Ingar Bergmann’s 1973 miniseries, Thompson created what appeared to be a perfectly appointed three-story home in Boston on a New York soundstage — each room reflecting a different dimension of the characters’ deteriorating relationship. In Alejandro Gonzalez Iñárritu’s Birdman, it was the claustrophobic and maze-like theater where the characters are trapped that won him the Art Directors Guild Award for production design. For Bradley Cooper’s Maestro, the home in question was a stately, sprawling colonial in Fairfield, Connecticut.

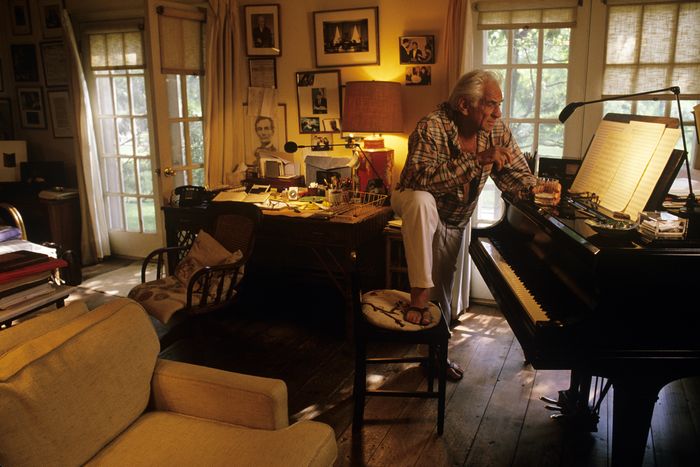

While the other homes in the film — the Bernsteins’ apartments in the Dakota and the Osborne, Leonard’s loft above Carnegie Hall — were meticulously built from the ground up, Thompson never really considered re-creating the Fairfield house that Leonard Bernstein and Felicia Montealegre purchased in 1962. It’s the home where Bernstein composed 28 years’ worth of work, where the family spent nearly every Thanksgiving and Passover, and where two of their three children still spend summers. “We really pushed to go there,” Thompson says of filming at the house. The choice was more expensive, but the intimacy of the space unlocked something essential about the family. “It was the most informative piece of the puzzle in terms of giving us details of their relationship and how they lived,” Thompson says. “I mean, I was able to look through all their junk drawers.”

Ahead of the Oscars, I talked to Thompson about what it was like to design in and around Bernstein’s real Fairfield home, getting to know the ghosts of Leonard and Felicia (down to the material of their bathrobes), and the thrill of stumbling upon long-forgotten artifacts and objects in the barn.

What was the house like before you’d gotten there?

I think because the kids are in the business of Leonard Bernstein, they’ve left the house pretty authentic to what it was when they were children living there. Felicia decorated the house and sourced most of the decoration from flea markets in the area.

It sounds like such an intimate process.

I mean, I was able to look through all their junk drawers, which informed a lot for the other set pieces.

Tell me more about these junk drawers.

Oh, yeah. Lots of junk drawers and those things you would hang on the wall in the kitchen from the ’70s — you’d stuff notes in them, and keys, and crayons, and Scotch tape. We were finding lots of old bills from the gas-delivery service.

Favorite discovery in the house?

I think it was finding dozens of Felicia’s paintings in the barn. Felicia was a failed painter. When they met, she was more famous than Leonard, but then his power eclipsed her creativity at times. They wanted to have a family, she had to sacrifice a certain amount for him to travel, so she would try and find other creative outlets. She loved to paint, though she never considered herself very good. So I was able to uncover all of these paintings that she did when they were traveling in Europe, or spending time in the country.

What were they like?

Mostly still-life and figurative paintings. She painted her kids a lot. It was really interesting to think about when she painted them, and where they would serve the house and the film best. We hung them in the rooms that felt appropriate in terms of time period and emotional context. We also found art objects and paintings made by their community of artistic friends and got to weave those in as well.

How did the house change?

I strategized with my art team about how we would make changes, which were mostly in set decoration, not construction. Nothing changed too dramatically. We’d refresh lampshades. And then we made it feel more vibrant by moving artwork around and adding in color. Me and my set decorator would look around and think, Let’s replace that, but keep that arrangement, and let’s keep the piano where it is but slide it this way for camera. We had to get rid of a lot of the technology — all the TVs, and the music equipment and the alarm systems. We replaced light switches too, things like that. Because they did update it to make it comfortable for them in today’s world.

We filled in because it felt a little … I don’t know how to say this politely, but it felt a little worn in. We moved furniture around. We recovered some of the furniture that had been faded. One specific couch — where Felicia, Tommy, and the kids are sitting and playing a game — was recovered in a maroon fabric that matched the original. We sourced a lot from used-furniture shops in Connecticut, because we figured that’s what Felicia would have done.

How did being in the house affect the filmmaking?

The emotional core that we were trying to extract between these two characters was highly informed by spending time in Fairfield, being in the house, and feeling the ghosts of how they moved through the rooms.

Can you describe some of these ghosts?

There were still things in the house like bathrobes and day dresses in the closets. They had towels with their initials on them. It was eerie at first, but then it became wonderful to be there and discover things.

When you got there, did it feel modern and lived in? Or something like a museum or mausoleum to Leonard and Felicia.

Oh, they live there. You can tell.

It’s mostly Jamie, the oldest daughter, and Alexander, the middle son, who still spend time there on the weekends. Nina, the youngest daughter, had less to do with it. Jamie’s very into running the business, so for her to be in her father’s house — also she was a teenager when they were living there — has deep meaning for her.

Did you ever consider reconstructing the house?

We considered going to another location, just for financial reasons because it would have been cheaper not to move the company up there. And we thought, Let’s go through the exercise of looking at country houses up there that have pools and all the elements, but every visit seemed wrong. So we really pushed to go there.

But the other major sets were builds.

We were trying to go to the real Carnegie Hall, the real Ely Cathedral, the real Tanglewood. We felt those were important set pieces for the film. The Dakota is legendary, but it’s impossible to shoot there. So we had to reconstruct that, and that was painstakingly done to make it feel like the rest of the movie. We didn’t want any of the builds to feel like they were on a stage. We built the Carnegie Hall apartment, the one from the beginning, with the skylights. He did really live in a loft like that above Carnegie Hall, so we used that as reference and built a space out that worked for the long tracking shot. And the Osborne apartment, where the Edward R. Murrow interview takes place, was built. And I think, to bring it back to filming Fairfield, I could take that knowledge and move it into other places. The Dakota was really dark because it was a really sad time in their relationship, which the architecture suggests. The Osborne was much lighter.

Bernstein would move artwork with him from apartment to apartment, and they would acquire things that would gradually either end up in the Dakota or in Fairfield. So we did that with set dressing, even though we knew it wouldn’t be noticed, we knew it would be felt. It helped us frame that and get it to feel like each place was layered with history and their past.

What about the Connecticut house changed most dramatically?

The studio where he wrote a lot of the music was in the back cottage, and that had been turned into a studio apartment with a galley kitchen. The kids don’t use it as a studio. So that studio, the original studio, was re-created, and all the set dressing was given to University of Indiana, and the Indianapolis School of Music, so it’s documented exactly the way that it was. We took that research and re-created it there. The wallpaper was all original. And the paintings on the walls were all picked out by Felicia.

It’s actually mentioned in a scene — Tommy stops next to a painting and asks if it’s Felicia’s.

Yes, Bradley made sure of that. Felicia liked small prints. Like in the master bedroom, it was a small print. But the most noticeable one is in the stairway, when she’s standing at the top and Leonard comes in with Tommy Cothran. That hallway is in a large floral pattern. And because it didn’t get sunlight, the colors were still vibrant. I did some research because I wondered if we should replace it, or duplicate it, but the colors were so much like the original that we decided to keep it.

What was Felicia’s taste like?

Her taste was eclectic and unpredictable. She used decorators sometimes, but Connecticut was all her. In the entryway in Connecticut, she put lattice on the walls to make it feel like a country cottage. And then she had some lattice wallpaper. She loved wicker, but hated painted wicker.

Isn’t there a painted white wicker set in the living room at some point?

There’s a bright-white set in the living room that you see in the scene when she jumps into the pool. That has all painted white wicker.

Tell me about the rugs.

We replaced the rugs. They were very simple wools and sisals. But they were really worn. So we replaced them in the original design so that it would remain authentic, but we’d just leave them for the kids. They told us that we left the house in much better shape than when we had arrived.

Was there a level of stress shooting in a real home with real stuff?

Yes. However, it’s been so much worse on other movies. The crew was small, no guests. And the crew was incredibly respectful to the Bernstein family.

The garden plays almost as significant a role as the house itself.

It wasn’t manicured, it was bucolic. When they were having their romance, we went to Tanglewood, which was a big part of their dating life and their courting period. We had a lot of nature scenes there, and we tried to parallel those to the yard in Fairfield — and the scenes in Central Park — to express the importance of that to them. It’s subtle, but it’s felt.

It feels like the pergola holds particular importance.

You’re right. I think it served as a motif that would tell us where we were. The interview with John Gruen — it’s Bradley’s background. We’re in the pergola when Leonard and Felicia are arguing on the lawn chairs, after Bernstein brings a surprise guest to the house. In that moment, it’s so awkward. You feel so uncomfortable. It’s almost like you’re eavesdropping.

I loved all of those long lens shots. There’s one scene when they’re fighting upstairs, and we’re looking into the room through a mirror, and Leonard’s taking his pants off. And we never cut.

It’s so naturalistic, isn’t it? Carey and Bradley really became these characters so that they could play a little bit. They were both so embedded in Felicia and Leonard.

Do you prefer the experience of shooting within real spaces versus reconstruction or constructing a space?

I like it all. I really love building and the challenge of making something feel so authentic that it’s hard to tell what’s real and what’s not. But I’m a designer that’s a New York designer, and I know New York, so I get hired for movies in New York. When Bradley met me, he said, “I want it to feel like it’s locations, I don’t want it feel like it’s on a stage.” So it is fun to make something that you research and that’s by the book. Locations are great and exciting — but sometimes you can’t get the shot.