In 2023, the developers of New York will open at least five new towers with private pools. The price of entry to most is pretty steep. From the rooftop pool of the Suffolk on the Lower East Side, residents can look out onto the towers of the Financial District while paying up to $10,000 for a two-bedroom. At the Ruby Chelsea, where a two-bedroom is listed for $15,000 a month, rooftop-pool swimmers can enjoy a panoramic view that includes the Empire State Building. The pool scene is even more rarefied on the roof of the Mandarin Oriental, where residents and guests paying more than $1,000 a night can swim in the 75-foot-long lap pool against a backdrop of Billionaires’ Row supertalls and Central Park.

The city of New York, on the other hand, has opened a total of five new public pools in the last fifty years. Over the same period, developers have built at least 434. This past Sunday, the city’s 53 free outdoor public pools closed for the season (at the end of a historic September heat wave, no less), effectively leaving the vast majority of New Yorkers without access to a free pool until next year.

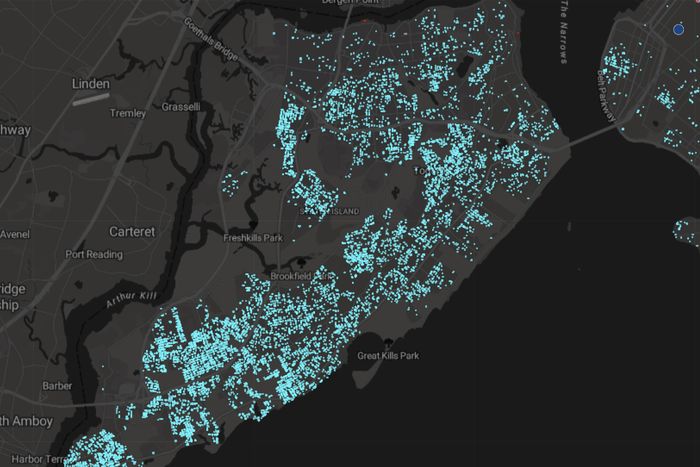

Two years ago, we first reported on the explosion of private pool construction in Urban Omnibus and New York Review of Architecture. We assembled and mapped our original list of as many private pools as we could manage. Since then, we have updated our tally: Developers have built an additional 45 buildings with pools since 2021. In contrast, the city has announced — but not yet built — just one, in St. Albans, Queens. They are all viewable on the interactive map below.

Private Pools in New York City

We started this work after reading Heather McGhee’s book, The Sum of Us, in which she pointed out that the desegregation of public pools in the 1940s led to a boom in private-pool construction — many communities chose to close their public pools rather than integrate them. In 1952, there were fewer than 15,000 backyard pools in the United States. By 2021, there were 10.4 million. At the same time, investment in public pools withered. In some cases, cities even filled in their public pools or sold them to private clubs.

New York did not follow this pattern exactly. Its public pools were never segregated, and in the 1960s — under Mayor John Lindsay — it actually went on a building spree, building dozens of vest-pocket and mini-pools. But after the financial crises of the 1970s, the government effectively stopped building new public pools. However, unlike many other cities, New York never sold any of its public pools, and the one that it did close for decades — namely McCarren — was eventually renovated and reopened. It did see the same trend, however, in the rise of private pools. Since 2016 alone, developers have built 175 towers with pools. None of this construction has an explicit racial agenda, but it would appear that it has only contributed to a longstanding racial divide. Today, only 8.7 percent of white New York youth do not know how to swim, compared with 25.8 percent of Latino, 34.3 percent of Asian, and 35.6 percent of Black children.

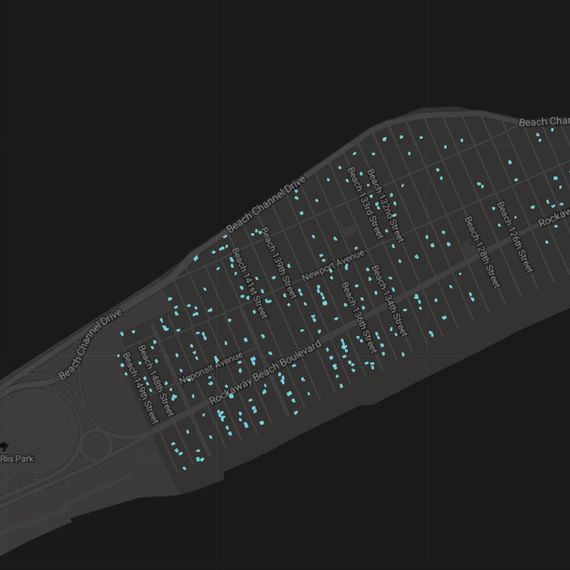

Counting private pools is not easy. There is no central log for reference. But pools are, by now, nearly standard amenities in luxury properties, which means that sometimes these largely inaccessible bodies of water are photographed, publicized, and even better known than their public counterparts. Therefore, it is possible to describe with some precision the pool at the top of the Suffolk, not because anyone invited us over, but because it is the splash image on its listings page. Using StreetEasy and Kayak, we could assemble a database of residential and hotel buildings with pools (it does not include pools at private clubs and schools). Some of these buildings have multiple pools: Renzo Piano’s 565 Broome Soho has seven. Soori High Line has 16. Sometimes a whole complex of buildings, such as the 20 towers of LeFrak City, shares just one pool. We also used an ArcGIS dataset to map New York’s backyard pools. We do not have an address for each one, but they tend to be concentrated in neighborhoods that are predominantly white. Whitestone, on the Long Island Sound, with about 330 pools, is 57 percent white. Neponsit on the Rockaways, which is 91 percent white, has 214 backyard pools, while the rest of the Rockaways has far fewer. An aerial image of Mill Basin, which is 67 percent white and has 351 pools, looks much more like a subdivision of Phoenix or Miami than a neighborhood in New York. Most of these backyard pool enclaves are also located near the ocean.

As of today, our list has 497 residential towers with pools and another 14,420 in backyards. We focused our search on residential and hotel developments with pools and didn’t include those at schools, colleges, gyms, or private clubs because we could not find a satisfactory comprehensive list of them. All told, New York has about 15,000 private pools. Compared to that, the Parks Department has 65. And as of Sunday, when the 53 outdoor pools closed for the season, it has just 12. Sixteen city council districts do not have any Parks Department pools at all.

Of course, not all pools are created equal, points out Park Commissioner Mark Focht. New York’s largest public pool, Astoria pool (currently under renovation), can hold 2,178 people. Highbridge Pool can accommodate 1,800. All of that capacity adds up: “We serve on average 1.5 million people a year — a lot of people for a ten-week period.” StreetEasy does not list pool capacity, but most of the pools in private towers look pretty modest — good enough for standing in with a drink perhaps, but not doing laps, and definitely not throwing a party with 1,800 of your neighbors. Moreover, while it is not clear how well-maintained all of those private pools are, the city has committed almost $1 billion to renovating and building public pools and their associated facilities.

Nevertheless, all of that capacity still shrinks enormously each year when the public pools close for the winter. The indoor pools that are open in the cooler months are all parts of recreation centers that require a membership fee for everyone over 18. Total membership at the city’s rec centers is just 121,000.

It’s understandable why the city might be reluctant to build more public pools. If their primary purpose is to keep New Yorkers cool, the city has other, more economical ways to provide access to water during the hot days of summer: 14 miles of beaches, all of which are open to swimmers from Memorial Day to the Sunday after Labor Day and 850 spray parks in playgrounds across the city. The spray parks are open more days (from April to October) for more hours (from 8 a.m. to dusk), and they do not require lifeguards. At this point, every playground renovation includes a spray park, all of which are designed in-house by Parks Department architects.

Some would argue that the primary purpose of public pools is to provide children with a summer activity. After all, the outdoor public-pool season is determined by the start and end dates of the school year. This has been the case since Robert Moses led the construction of the public-pool system with support from the Works Progress Administration in the 1930s. It is, according to Focht, a symbiotic system. “The vast majority of our patrons are kids,” he said. “Many of our lifeguards are students,” notes Focht, and would be unavailable to work after September 10. There are 48 pools in New York’s public-school system, 33 of which will open when the Park Department’s 53 outdoor pools close (the other 15 are under renovation). Of course, given there are a million students in 1,800 public schools, 33 pools represent a tiny fraction of young people who can swim during the school year.

But what if the most critical function of public pools is a space to swim and to teach people how to? Marta Gutman, dean of the Spitzer School of Architecture, who has researched New York’s pools and the era of WPA’s investment in them, notes that teaching kids how to swim was a primary reason behind the original push to build public pools. Nationally, drowning is the leading cause of death for children under four, and among children ages 5 to 14, the second leading cause of unintentional injury death. In New York State, the racial disparities between those who know how to swim and those who don’t translate directly into disparities in those who drown: The rate of drownings among New York State’s Black population is double that of white and Hispanic people.

Gutman believes schools should require every student in the school system to learn how to swim. But she does not think this means the city needs to build more pools. In 2011, Gutman joined the “Swim Council” of Swim for Life, a program organized by Adrian Benepe, then commissioner of the Parks Department, to prevent needless drowning by teaching second graders how to swim. She helped facilitate a partnership between the program at the Parks Department, the Department of Education, and CUNY to provide public-school students with swim lessons at a City College of New York pool. The program was paused during the pandemic, but she thinks it pointed to a promising model: mobilize all of the city’s pools, be they in parks or schools, colleges or clubs, and make them available for swim lessons. This spring, a package of City Council bills also proposed to keep school pools open year-round, but it has not been passed.

If the city did in fact partner with more of its private and institutional pools, a number that steadily grows every year, that could mean this weekend’s public pool closures would not spell the end of the swimming season. For many, it could actually be the beginning of one.