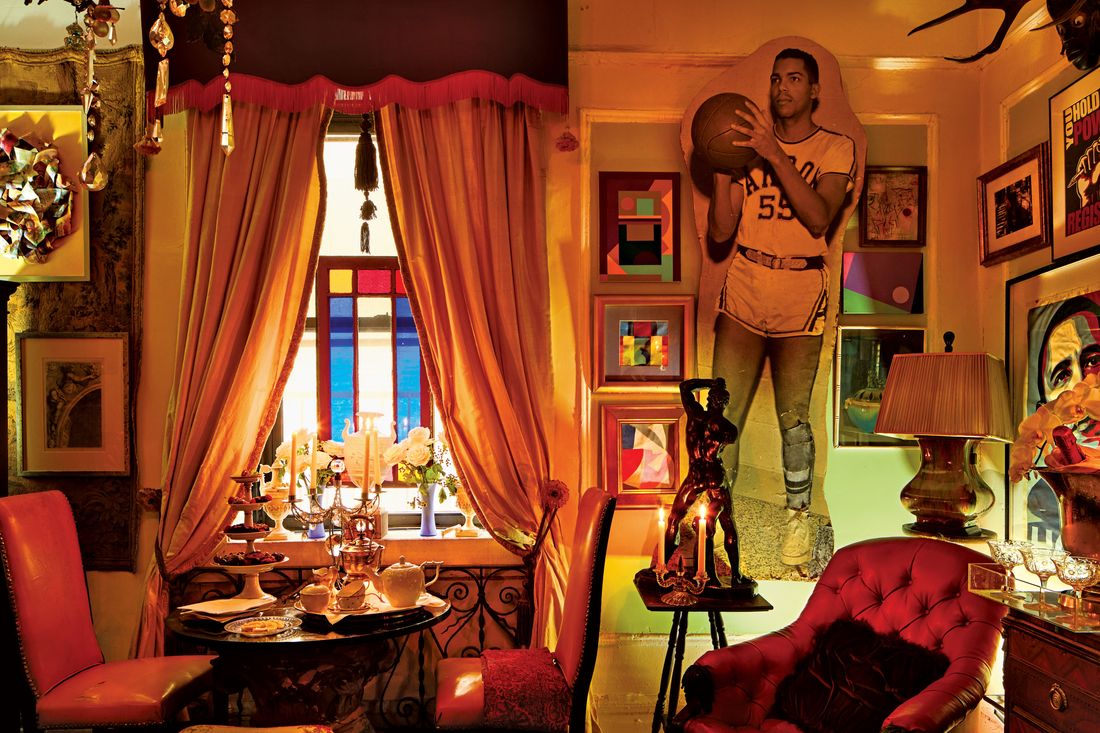

One imperative of my decorating is candlelight,” says author and architectural historian Michael Henry Adams of his Harlem apartment, dense with objects, layered with meaning and, since it’s at the back of the building, lacking in much natural light. And so he lights candles, even during the day.

He has been that lone figure shining a light, voicing his rage, at times getting arrested protesting the demolition of Harlem and New York City history, church by church, building by building. He’s been at it since 1985, when he arrived from his hometown of Akron, Ohio, with the intention of attending the historic-preservation program at Columbia University, “which I eventually did,” Adams says, after stints as a messenger on Wall Street and a bookseller at Scribner’s and working for designer Thomas Britt. Over the decades, he has been an advocate for the preservation of the Audubon Ballroom and the Renaissance Casino and Ballroom, among many significant markers of Harlem history.

Adams has been in his one-bedroom rental near St. Nicholas Park since 2007. It’s filled to the brim, as his other apartments have been, with family and neighborhood history. It’s decked out with sumptuous fabrics, a throwback to a genteel and slower-paced era more than a century ago, when tea was served in the afternoon — as he served me when I visited — and everyone’s phones were not constantly, urgently pinging. Adams’s instinctual feel for those previous times, and his encyclopedic knowledge of furniture styles and architectural eras, has led him to write two books: Harlem: Lost and Found (2002) and Style and Grace: African Americans at Home (2003).

Ask about anything in his apartment, and you will not only learn its detailed provenance. “The plum-colored valence is from the Park Avenue apartment of a friend’s mother,” Adams says. “My friend Mario Buatta was her decorator, and Mario gave me the cloth and fringe to redo them.” He describes himself as, among other things, “an inveterate collector of treasures found in the trash.” The mantel over his fake fireplace, he recalls, “was spied as I awaited the bus one night on Madison Avenue near the Carlyle Hotel.” Nearby, there’s a fragment of a silvered garland of fruit and flowers from the Audubon Ballroom, where Malcolm X was assassinated. And then there is a piece of “egg-and-dart molding from the Lafayette Theater, where Orson Welles’s Voodoo Macbeth opened in 1936.” There are also many family photographs, including a life-size one of his father when he was a college basketball star.

His rococo console (upon which he has placed an Empire Cupid clock) rests on “marvelous” washable woven plastic mats that he describes as “one of my happiest finds, sourced in shops on 116th Street, the main artery of Harlem’s Little West Africa.” Adams also points out a machinemade tapestry in one corner of the room “that once hung in the studio of twin photographers Morgan and Marvin Smith.” He continues: “They were next to the Apollo Theater. Billie Holiday, Harry Belafonte, and Lena Horne stood next to this.”

More Great Rooms

- The Water-Tower Penthouse in the Bronx

- Rosario Candela Invented the Upper East Side Apartment

- From a Downtown Loft to a Sutton Place Classic Seven