This article was featured in One Great Story, New York’s reading recommendation newsletter. Sign up here to get it nightly.

Long after the shutdown of indoor dining and the advent of socially distanced picnicking; after takeout cocktails and “Cuomo sandwiches”; after to-go-box trash ziggurats and $69 delivery-app veal parms from Carbone; after Jersey-barriered roadway cafés and tabletop hand sanitizer and QR-code menus and a wave of shuttered restaurants; after the run on PPE, the rush for PPP, 25 percent capacity indoor dining, contact tracers, and Plexiglas; after masking up to pee and unmasking to eat; after vaccines, vaccine mandates, Excelsior Passes, and easily faked screenshots of Excelsior Passes; after a vaccine brawl at Carmine’s and a germ-shedding Sarah Palin at Elio’s; after subzero date nights under feeble electric heaters in yurts, igloos, and corporate-branded “winter villages”; after the return of full-capacity indoor dining; after Delta and Omicron, after boosters and the bivalent jab; after mask edicts ended and return-to-office drives began — after New York’s pandemic era faded out — one key vestige of COVID-19 remained right there on the street: the outdoor-dining shed.

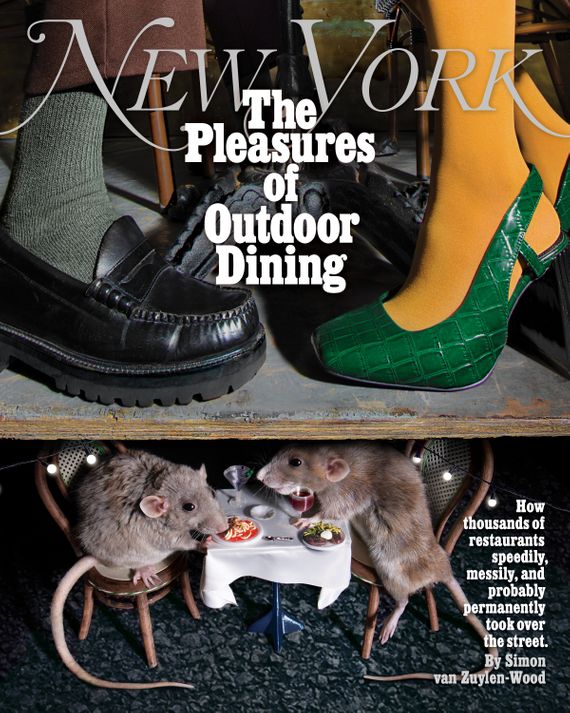

The mass extemporaneous construction of alfresco structures probably represents the speediest reshaping of the built environment in the city’s history. Practically overnight, more than 12,000 of them mushroomed on sidewalks and roadways, running the gamut of craftsmanship, taste, and COVID-mitigation plausibility. Daniel Boulud’s flagship erected upholstered cabanas that felt almost inappropriately lush given the circumstances. The shanty outside Dumpling Man on St. Marks is unspeakably hideous, its colorless wood fragments hammered together so arbitrarily that you would rather eat in a pile of Lincoln Logs. The invasion Eurified swaths of the city, sort of, and normalized the practice of eating inches away from careering trucks. You could say it democratized dining, and you could say it privatized the streets. Inarguably, the shed insurgency has been a counteroffensive against the homogenization of the city, breeding wildness where before there was Duane Reade.

Grand or decrepit, the new structures wouldn’t exist but for an emergency measure of the pandemic — the Open Restaurants Program hastily authorized by then-Mayor Bill de Blasio. City planners of yore can only salivate at how rapidly and painlessly this municipal revolution came off. Dan Doctoroff, the architect of Michael Bloomberg’s rezoning of New York, tried to convey to me the torture of doing almost anything under ordinary circumstances. When he joined City Hall as a deputy mayor, he became fixated on remodeling dilapidated newsstands, bus shelters, and public toilets. Similar efforts had been stymied since about 1978. “We had to develop a plan, we had to get it through City Council, we had to issue a request for proposals, we had to work through the RFP, we had to award it,” he said, “and then it took time to fabricate the things and put them on the streets.” It cost Doctoroff nearly five years of toil; his grand plan for 20 commodes withered. “We ended up doing one,” Doctoroff said. “Literally. I inaugurated it on my final day in office.”

Outdoor-dining options arrived so fast we never even properly named the things. Streetery is cute, though shed — conveying humility, pluck, and slanted roofs — is more common. There remains no uniform term because the category contains multitudes, from simple chair-table-umbrella combos to bubbles, boxcars, pagodas, faux RVs, and literal houses. Jacob Siwak, the chef-owner of Forsythia, refers to his structure — which was set on fire twice by an arsonist sommelier — as a pergola. Deborah Williamson, the owner of James in Prospect Heights, describes her canvas-swathed structures as patios, though they are clearly not.

Booking on Resy, sight unseen, is pure chaos. In one recent period, according to the company, restaurants described their outdoor tables with 113 unique names, including heated chalet, veranda outdoor (where else would it be?), and fern garden. “You just want to know, Am I going to get rained on?” says a Resy employee who doesn’t want to reveal her name. “Is this going to be cute enough for a date?”

Some customers call them sukkahs, after the Jewish festival of open-roofed huts. Larry “Ratso” Sloman calls them favelas. A Prince Street polymath who ghostwrote Mike Tyson’s memoirs and had a cameo in Uncut Gems, Sloman feels they are primarily giant incubators for rats. “People say we’ve always had rats,” he says. “No, we’ve never had fucking rats like this in New York City. They’re getting bigger and bigger eating leftovers from all the fucking tourists who want to sit in these miserable-looking sheds and think that’s some kind of an authentic New York.” He is among those who now see the city in zero-sum terms: The streeteries’ gain is the neighborhood’s loss.

Sloman is correct, if only in the sense that rats are indeed among the many stakeholders maneuvering for advantage in this reordering of the street space. What began as a parable about the city’s resilience has evolved into a honking mêlée among landlords, urbanists, restaurateurs, homeowners, and the menu-reading public over the most precious resource on earth: New York real estate. As a spectacle, the land grab is thrilling to behold. But is it just? “I don’t believe we should be ceding public land, public space, for private commercial gain,” says State Assemblywoman Deborah Glick, who represents the shed-packed precincts of Soho and the West Village. Also: “Most of them are thrown together and look like crap.”

De Blasio, naturally, sees the best in them. “I don’t think anybody anticipated the spiritual, atmospheric impact,” he says, which sounds mushy but is basically right. “It gave us a sense that we could make it through the pandemic, that our strength was visible.” But even the father of Open Restaurants knows there are duds. “I went by one last week, and it was like, there is literally nothing aesthetically pleasing about it,” he says. “And you know this place Winner?” he adds, referring to the madly popular Park Slope bakery. “Their shed is not so special.”

The eyesore factor was obvious to Doctoroff more than a year ago. “The dining sheds look charming and quirky today, but they were built hastily and vary in quality and design. In another year or two, they are going to start looking shabby,” he wrote in a Times op-ed, calling for them to be razed and rethought while the moment for blue-sky civic thinking was still alive. What if street space could be used for “dynamically priced loading zones,” he wondered, with revenues funding the MTA? “We need to think bigger than the dining shed,” he wrote, a technocrat’s appeal.

But this is simply not Michael Bloomberg’s gleaming Swiss watch of a metropolis anymore. It’s a more brazen, ad hoc city again under Eric Adams, the after-hours mayor. Right now, an inflection point is upon us: The improvisational process that birthed streeteries is over, and the government is approaching a consensus on how to make them permanent. While those rules are still being written, a few outcomes seem likely. Rickety plywood sheds will come down — eventually; it could take a while — and be replaced in many cases by more up-to-code structures. And New York will continue to allow restaurants to commandeer an astounding amount of public pavement.

New Yorkers have already adapted. In lower Manhattan, a hostess who demanded anonymity told me Mila Kunis was eating in her employer’s shed one day when a rat scurried beneath her feet. Elegantly, she folded her legs up onto her seat and continued to enjoy her bistro fare.

It started in Crain’s, of all places. In May 2020, with indoor dining still banned and mass unemployment a distinct threat, then-City Council Speaker Corey Johnson and Andrew Rigie, the influential head of the city’s restaurant lobby, wrote an op-ed urging the city to let restaurants take over the streets. De Blasio recalls buying in after hearing a convincing Zoom pitch from Rigie’s Hospitality Alliance. On June 18, he rezoned the city by fiat, allowing New York’s 27,000 restaurants to annex the land just outside their windows.

We’ve become inured to eating en plein air, but the Open Restaurants Program was bracingly new. Outdoor dining hadn’t previously been allowed in much of New York. Just 1,224 restaurants had licensed sidewalk cafés, most of them in Manhattan. Fees were steep. In most of the borough, restaurants paid a minimum of $2,579.62 a year for any café taking up 70 square feet or less, and the biggest spaces forked over almost $20,000. Suddenly, outdoor dining cost them nothing. And for the first time, the establishments were allowed to set up not just on the sidewalk but in the street itself.

That is why de Blasio assigned oversight not to the Department of Consumer Affairs, which ran the old café program, but to the Department of Transportation. The DOT slapped up a web page with a rendering of what was then a prototypical setup featuring three small tables near a street corner. Regulations evolved fitfully from there: Roadway barriers must be 30 to 36 inches tall; don’t string heaters within five feet of trees; a shed with two “open” walls, whatever that means, is subject to different restrictions than a shed with one.

The rules were purposely lax. Before the pandemic, getting a sidewalk café approved involved an excruciating application. (“Submit seven [7] copies of the scale drawing plan signed, stamped, and sealed by a licensed New York State architect or engineer.”) In crafting the COVID program, de Blasio says, he got some advice from — who else? — a Park Slope restaurant owner. The guy told him if the application to build a streetery was remotely cumbersome, nobody would bother filling it out. Thus came an online “self-certification” process, the restaurant equivalent of clicking through an Apple user agreement as mindlessly as possible.

The red-tape slashing worked. In the first 24 hours of the program, 1,950 restaurants self-certified, immediately clearing them for open-air service. And once the structures were up, the DOT was intentionally lenient with violators. Restaurants were given three inspections to fix any issues that arose. It’s not clear how often that third visit was happening. The DOT has just ten inspectors assigned to outdoor dining, and they’ve handed out only 67 fines. Meanwhile, a crack team of interns from the Council Speaker’s office once studied the sheds of the West Village and found that 93 percent were breaking at least one rule.

A handful of factors did have the potential to doom a shed: No streetery could be erected in a bus lane, bike lane, or no-standing zone. Nor could it take up more than the width of the restaurant’s brick-and-mortar frontage. If a restaurant was lucky enough to be on a corner, though, it could have two sheds. The lesson was to grab what you could.

Even though it was their reason for being, the COVID factor — the way the structures did or did not provide diners with a well-ventilated space to take off their masks and breathe together — was generally not treated with scientific precision. In Fort Greene, Tobias Holler ordered 14 pint-size greenhouses from Amazon and installed them outside his Black Forest Brooklyn beer garden. Customers sealed themselves in and used QR codes to order their weisswursts, which were handed over through a briefly opened door as a prisoner in solitary might receive his tray of gruel. After the diners left, a server used a battery-powered spray gun to mist the space with sanitizing solution. “We thought it would, uh, ‘kill the air,’” Holler says.

That’s how we thought back then. Nobody knew anything. “Old ladies would come in and ask, ‘What’s your safest table?’” says Roya Shanks, maître d’ at the Odeon. “I’m not a doctor! ‘Uh, well, it’s open on the end. Maybe you’ll get a good breeze there?’ I was just spinning.”

Architectural standards and ambitions, and what it all cost, were just as scattershot. Veselka’s owner, Jason Birchard, says he paid his contractor about $15,000 to build his sturdy East 9th Street shed, its tall partitions giving it the feel of a horse stable. The owner of Lola Taverna, Cobi Levy, says he dropped $200,000 to build and maintain a birchwood-and-fresh-flowers creation off Sixth Avenue and Prince Street. (Birchard doubts this number: “What did they have, marble floors?” It was eventually dismantled for being in a no-standing zone.)

Gerardo Guzman, a general contractor who built structures for Veselka and a number of other restaurants, discovered that one way to save money was not to build a floor at all. This wound up being smart in at least two other ways. Eating directly on the pavement better replicates the idealized Parisian experience, where people don’t eat in oversize shoe boxes. And concrete is much easier to hose down than a wooden platform, under which all manner of toxicity lingers. Guzman’s clients with floors call him regularly, complaining of “funky water.”

By the summer of 2020, according to Guzman, all the local branches of Home Depot and Lowe’s were sold out of two-by-fours. Where he could find them, at lumberyards upstate or in New Jersey, they cost $12 apiece, up from the usual $4. Part of the crunch came from an unexpected run on lumber during the George Floyd protests, as businesses bought up plywood to cover their plate-glass windows. Simon Kim, owner of the Michelin-starred Korean steakhouse Cote, says that when the protests ended, he simply took the plywood off his windows and refashioned it into the six tables he added to a “rose garden” on West 22nd Street.

From simple wooden forms, the streetery mutated, driven by weather and owners’ realization, come spring 2021, that COVID would linger. Home Depot trucks reversing out of their loading zone kept bumping into the Cote shed, so Kim dismantled it. He wanted something fancier, but his restaurant wasn’t generating any money so he made a bargain with the Devil — or, that is, “a famous bank that does credit cards.” In exchange for cash, Cote guaranteed reservation slots to the bank’s preferred customers. Kim used the money to hire the architecture firm GRT to create a gable-roofed five-room dinette sheathed in a waterproof black material. This led to a new problem. “Our thing was a little posh, and with a curtain,” Kim says, “so the homeless sleeping in the structure was an issue.” He began locking it up at night.

Restaurateurs were discovering what consultants call externalities. “Human shit,” says Katie Richey-Tonery, who owns the Ditmas Park wine bar King Mother. “Coke bags.” If people weren’t boosting her $250 heaters, they were plugging them in and hanging out all night. But after operating for months in the red, she was on the side of extra space. Richey-Tonery more than doubled her seating.

The streetery created a bunch of weird new markets in a golden moment for hustlers and entrepreneurs. As cold weather approached in the first COVID winter, Derek Kaye predicted that New York would reverse its long-standing ban on restaurants’ use of propane tanks for outdoor heating. Kaye operated a Mexican-Japanese taco-truck business; trucks are allowed to use propane, so he was familiar with the product and knew how hard it was to find. “There are zero places in Manhattan,” he says. In September 2020, he began buying up domain names: nycpropanedelivery.com, brooklynpropanedelivery.com, etc., until he was squatting on 20 of them. On October 14, de Blasio signed an executive order allowing restaurants to use propane heaters. Within days, Kaye became New York’s go-to propane guy. He began with La Pecora Bianca’s handful of locations, then expanded to Café Luxembourg, Little Owl, Bluestone Lane, and more. Every day at five or six in the morning, Kaye and his squadron of six truck drivers would head to a warehouse in Mount Vernon. Each truck could hold about 256 canisters. Kaye would buy propane for $20 and sell it for as much as $30. At the peak of winter, he says, he was delivering to as many as 400 restaurants.

In October 2021, de Blasio rebanned propane. Kaye now does residential deliveries.

The restaurateur Danny Meyer has watched the streetery boom with some skepticism, especially where rivals have outfitted their structures with luxe amenities like climate control and music systems. (Amplified sound, by the way: Against the rules.) “At that point, you’re not dining outdoors,” he says. “It’s a land grab to get more seats.”

Except you are, of course, eating outdoors. In the fall of 2020, Meyer found himself dining in the middle of the road. “It was in some type of very, very flimsy structure. Literally every time a bus would come down Second Avenue — and you learn very quickly that Second Avenue is a very busy bus lane — the entire building would shake,” he says. “I spent almost every bite pretty convinced that this was my last meal.”

When I ask if he’ll be dismantling his own sheds, though, he says no: “The city’s not charging rent to be there, and I don’t have a place to put them. So unless you give me a disincentive to keep it up, I’m just going to keep them up.” Plus, he says, weekday lunch isn’t back yet and you’ve got to make up the covers.

The main ideological fight over outdoor dining breaks down pretty neatly between NIMBYs and YIMBYs — or at least that’s how the two factions disparage each other. The pro-bike, anti-car crowd tends to tag shed haters as a reactionary force bent on suffocating a once-in-a-lifetime opportunity to reinvent the city, and for what? Just to keep their neighborhoods quiet and hang on to their parking spots?

The shed haters tag their opponents as smug technocrats who are in denial about how bad the noise-trash-feces situation really is — and, more significant, that they’re getting snookered by moneyed interests. In this latter view, a kind of shock-doctrine dynamic has arisen in which the hospitality industry capitalizes on the emergency of the pandemic to plot a deregulated takeover of communal areas. “It’s unfettered capitalism,” says Diem Boyd, a longtime Lower East Side community activist. “Do what you want with no oversight or enforcement.”

Both sides see themselves as the true progressives. “Using less than one percent of all parking spots in New York City, we were able to save 100,000 jobs and an entire industry,” says Cory Epstein, a spokesman for the urbanist advocacy group Transportation Alternatives. Boyd, meanwhile, calls the organization and similar ones a “big-tech–funded new urbanist moral majority,” who are “cosplaying grassroots organizers.” (Epstein’s group has taken money from Uber and Lyft.)

The hyperlocal press has squared off. Community newspaper The Village Sun is fully anti-shed, while the transit-focused Streetsblog sees the structures as a promising front in the war on King Car and goes scorched-earth against anyone who opposes them. Last summer, Streetsblog introduced a post about anti-shed activists as part of its “ongoing coverage of revanchist movements across the city to remove bike lanes, eliminate open streets, or discriminate against delivery workers by a small minority of New Yorkers who own cars.” One photo caption read simply, “Anti-open-restaurant protesters in the West Village are mostly White.” Boyd, for what it’s worth, is Asian American and doesn’t drive.

In the second pandemic summer, Boyd and 20 other members of an anti-shed advocacy group called Coalition United for Equitable Urban Planning, or CUE-UP, sued the city. The administration had declared that the Open Restaurants Program would have a negligible environmental effect, and these litigants begged to differ. The lead petitioner was Kathy Arntzen, who has lived on Cornelia Street with her husband, Leif, since 1989.

That West Village location is significant. Of the city’s 12,644 streeteries, half are in Manhattan, and about half of those are below 23rd Street. The streetery signifies something quite different there than it does in brownstone Brooklyn, to say nothing of the city’s more suburban enclaves. (There are just 189 registered in Staten Island.) With the exception of a few clogged stretches — Bedford Avenue in Williamsburg, Steinway Street in Astoria, Smith Street in Cobble Hill — it’s almost impossible to find the cheek-to-jowl shed bazaars, and the rifts they’ve created, that exist in the densest, richest borough.

Kathy chairs the Central Village Block Association and works at a foundation that raises money for a children’s hospital; Leif is an accomplished jazz trumpeter and a VP at a New Jersey–based transportation-logistics company. They can remember when Cornelia had a Sesame Street feel with “low-key, low-rent” storefronts like a bakery, a butcher, a little gallery. I meet them one night on the sidewalk. Their pocket of the city stopped being humble ages ago — at one spot, Kathy points to a building and says, “That’s where Taylor Swift used to live” — but for the Arntzens, the arrival of sheds cemented their cozy block’s devolution into saturnalia.

Cornelia Street is just 450 feet long, bracketed by Bleecker and West 4th, and it contains six restaurant sheds. To the Arntzens, each represents a different facet of squalor. Menkoi Sato, a ramen place, has a tiny shack adjacent to a kind of open-air rubbish depot where scavengers sift trash for eventual resale. Oppa Bistro is a casual Korean spot with a row of spaced-out fabric-covered outdoor booths. Against one side, there’s a giant turnip-shaped sack that Leif claims is a rat-mitigation tool, though it looks more like a discarded tree stump. Third is Tacombi, whose tubelike structure appears unique in that it attracts mice rather than rats (video footage bears this out); fourth is Palma, with a shed abutting a Kilimanjaro of garbage bags. Pearl Oyster Bar has a shed, Kathy says, that for a while was occupied by a man with two suitcases and a Citi Bike. And then there’s Silver Apricot, which maintains arguably the most infamous streetery in all New York.

On August 6, the New York Post ran the front-page headline LOVE SHACKS over an exposé about people having sex in dining sheds. Someone had sent the paper a video of a woman fellating a man in the Silver Apricot shed in full daylight. The article and an accompanying op-ed (“Mr. Mayor, Tear Down These Sheds!”) coincided with a reckoning at City Hall. Mayor Adams soon announced a task force to demolish noncompliant structures, and at a photo op in Koreatown, he personally took a sledgehammer to one that had belonged to a shuttered restaurant. (The administration says there’s no connection between the coverage and the mayor’s actions.)

Silver Apricot is, or could be, a special kind of eatery. After it opened, just a few months into the pandemic, Pete Wells lavished praise on its “synthesis of Chinese ideas and the Hudson Valley farm-to-table movement” in a starred review in the Times, and Eater described it as perhaps the city’s “most exciting new restaurant.” It was supposed to be tasting-menu only, but the brutal economics of COVID forced it to adopt more casual fare. The shed helped keep it alive.

After touring Cornelia Street with the Arntzens, I call Emmeline Zhao, Silver Apricot’s managing partner and sommelier, to ask about the challenges posed by her outdoor space. “Frankly, the challenges have been the neighbors,” she says. “Who walks by homeless people having sex and takes a video?” She sends me a video of her own — surveillance footage showing who made the original recording. It’s Leif Arntzen. (He confirms he did it, at 6:34 a.m. on July 20, while walking to his car. He drives to work in New Jersey.)

On at least one matter, they agree: Neither party is thrilled about shed blowjobs. The cops haven’t been particularly helpful about people loitering in her space, Zhao says. Cornelia Street’s problems are real, but they’re above her pay grade. “Restaurant operators don’t have a solution to the issues of homelessness and drug use,” she says. And Leif allows that Silver Apricot deserves some slack. “You can’t blame a restaurant owner for trying to do the best they can,” he says. “You can’t fault them for saying, ‘I’m allowed to do this, so I’m doing it.’ That’s why we’re so mad at the city.”

In October, an appellate panel discarded Kathy Arntzen and CUE-UP’s case on procedural grounds. The group is prepared to refile the suit when the Adams administration signs a permanent streetery bill into law. In the meantime, Leif has kept up his Cornelia Street camerawork. He recently sent me a video of two rats running into the space beneath a shed as well as photos of stagnant liquid, syringes, and a turd that somehow ended up on the outside of Silver Apricot’s shed.

Throughout the pandemic, Bobby Corrigan, the city’s foremost rodentologist, has been tweeting a simile: As a sunken ship becomes a shelter to fish, a dining shed with a suspended floor naturally becomes a habitat for rats.

Virtually everything about wooden streeteries, from elevated floorboards to plywood planters, makes for convenient rodent nests, feeding stations, and breeding grounds. The bags of soil that weigh many of them down — a DOT requirement to protect diners from wayward vehicles — make an ideal dank habitat. A wooden planter with exploded dirt all around it is a sign that a shed has been infiltrated. This fate befell the nifty David Rockwell–designed streetery at Melba’s in Harlem, which an employee told me had been terrorized by “furry friends.” If you are walking your dog and it starts going at a planter with vigor, this is why.

Common mitigation techniques include bait stations, the black boxes you’ll see in the corners of some structures. Another widely used deterrent is wire mesh, which is usually tacked to the very bottom of a structure and meant to keep rats from scurrying beneath the floorboards. These have the incidental effect of trapping detritus against the shed’s exterior, which in turn allows garbage juice to pool.

An employee at Kindred, a now-shuttered Mediterranean restaurant in the East Village, says the restaurant built a trap door beneath its wooden structure to lay down rat poison and, later, remove dead rats. Guzman, the prolific shed contractor, says he recently dismantled a particularly shabby structure belonging to a Soho bar. He claims roughly 50 rats scurried out from underneath as workers tore it apart. At his various work sites, Guzman has adapted. At Veselka, instead of putting dirt into the exterior planters, he installed tiny pre-potted plants that sit directly on the wooden structure. At Guey, he buried wire mesh six inches deep into each of his potted plants to discourage burrowing. (According to an exterminator I spoke with, anything small enough to burrow into a potted plant is probably a mouse, not a rat.)

Erika Chou, the owner of Wayla, has tried to maintain soil-filled flower beds on the exterior of her fetching dark-green structure. To ward off vermin, she filled them with cat litter, which apparently is a deterrent. Now, humans have become the pests. “We actually have neighborhood people who take our soil,” Chou says. “They will come with a plastic bag and take a little soil every day.”

There are some rat skeptics. When I bring up the topic with Forsythia’s Siwak, he gets heated. “I was interviewed by the BBC, and they asked the same question,” he says. “And it’s like, ‘There is no more garbage fabricated now than before the dining structure. There are no more rats now than before the pandemic.’” The problem, he says, is trash-collection protocol. “This idea of putting garbage out on the sidewalk is insane.” It’s true that rats feed on garbage and that New Yorkers throw their bags directly onto the sidewalk. It’s also true that rat sightings are way up. According to the Daily News, the city received 21,577 rat complaints through the first nine months of the year, up from 16,000 in all of 2019.

I heard murmurs of a serious rat situation at Dr Clark, the Hokkaido-style restaurant on Bayard Street. Dr Clark built one of the buzziest sheds of the pandemic. Diners would enter a stall, remove their shoes, and slip their feet into warm blankets below low tables. The restaurant’s owner, Yudai Kanayama (who attempted to build an illegal two-story shed at a different restaurant), had sought to re-create the wintry feeling of a thermal hot spring in northern Japan, in which people’s torsos are exposed to the elements while their lower halves stay toasty. Unfortunately, the setup was irresistible to vermin.

When I asked Kanayama about rats, he was coy. But a Dr Clark veteran, whom I’ll call Robin, told me the full story. “First of all, the Chinatown rat situation — everybody knows about it, that we have a very specific style of Chinatown rat,” she said, a breed that is “just a little more confident.” Then there was the structure, which she described as “rat condos.” “It was built with little levels and nooks and crannies — spaces for them to hunker down and make a home.” Sometimes the rats ran on a part of the structure Robin called a “superhighway,” where they would scurry atop diners’ purses and whatnot, then back down to the ground.

Eventually, the shed was removed, but only partly because of the rats. Judges and cops at Central Booking nearby were clamoring to get their stolen parking spaces back. The staff broke up the structure in late summer. “There was definitely a lot of garbage, and there definitely had been some sort of family of rats living underneath it,” Robin said, then paused. It felt like there was something else she wanted to say. She exhaled and continued, “I guess this is common knowledge of everybody else there, so I’m not going to implicate myself. But there was a mom rat giving birth and then she got scared and abandoned a couple of babies. It was pretty sad and also gnarly and, like, weird. ‘Oh, we just disrupted your ecosystem, but also we created it.’”

It is an entertaining quirk of history that the fate of outdoor dining is in the hands of a mayor who often seems to live in a restaurant — specifically, an Italian place in midtown owned by two of his friends, twin brothers with less than ideal criminal histories. Koreatown sledgehammer notwithstanding, it seems probable that the nightlife champion Eric Adams will deliver a program the hospitality industry likes.

Restaurateurs themselves, however, are still in need of reassurance. As I reported this story, several owners asked me to tell them what the future of Open Restaurants would be. So here is where things stand: The program de Blasio started was temporary, and it basically ran on autopilot, allowing restaurants to operate their streeteries with minimal oversight; in the background, a small team of staffers from DOT and the Department of City Planning has been working on the details of a permanent Open Restaurants platform. Those specs are being hammered out. Right now, a small-bore feud is taking place between City Hall and the Council about which agency gets to run the program. Eventually, it will come to a vote. Everyone expects for it to pass and for Adams to sign it into law.

The officials involved tell me wooden sheds won’t be permitted, so all the plywood ones you see today will have to be torn down. The structures that will replace them are likely to resemble something similar to a patio, possibly with standardized modular elements. The city’s chief urban designer, Erick Gregory, singled out the setup at Daily Provisions, on 78th and Columbus, as a solid rubric: an elevated wooden patio protected by water-weighted plastic Jersey barriers and flexible, tentlike roofing.

They will be relatively affordable to apply for. The current version of the bill floats sums in the hundreds of dollars, rather than thousands. But the days of “self-certification” are over, and local residents will likely have more opportunity to consider streetery applications and voice their objections. The sidewalk streeteries will probably be permitted year-round, and the roadside streeteries will be allowed only in warmer months (with perhaps some exceptions). There are still ample chances to shape the bill. Brooklyn Borough President Antonio Reynoso, an early champion of Open Restaurants, argues that a seasonal plan — requiring restaurants to pay for construction, deconstruction, and storage year after year — will price out diverse, mom-and-pop eateries. Other supporters fret that political meddling will move outdoor dining in a less progressive direction. Adams’s DOT commissioner, Ydanis Rodriguez, a former councilmember representing Washington Heights, started off well liked by the urbanist crowd, but his agency has been hobbled by staffing vacancies and has already missed targets on installing new bike and bus lanes. In October, Streetsblog reported that City Hall had held up a 5.4-mile bus lane* in Queens at the behest of Councilman Francisco Moya, an ally of the mayor and his first choice to be Council Speaker. (The administration says the lane* is still in the works.) “This is a mayor’s office that’s very susceptible to people’s personal opinions,” says someone involved in shaping the initial outdoor-dining program.

The shed skeptics in city government include outer-borough councilmembers with car-owning constituents — NIMBYs with literal backyards. Kalman Yeger of Borough Park has been the most vocal of this faction, habitually tweeting photos of gnarly sheds with hashtags like #shutdowntheshantytown. “In my community, having eight kids is normal. People drive minivans,” he says. The sheds were annexing their parking spots; some 8,000 have been lost citywide. Besides, he adds, it wasn’t fair to other businesses. “A restaurant with free space is next to a shoe store, a candy store, a grocery store,” he says. “None of them are getting free space. Only the special child of the last three years.” And then there are critics in the densest areas, like the lower-Manhattan councilman Christopher Marte, who is CUE-UP’s chief political ally. The program has made strange bedfellows of those who don’t see the point of sheds and those who feel overrun by them. Marte has more than 1,000 sheds in his district; Yeger has about 50.

Yeger and Marte are distinctly in the minority, though. Earlier this year, the city voted overwhelmingly to scrap the pre-pandemic zoning rules that blocked outdoor dining in much of the city. Momentum still resides with the streetery. In September, City Council Speaker Adrienne Adams, who represents southeastern Queens, remarked at an event that she would prefer to see outdoor dining limited to sidewalk, not roadway, seating. Restaurant Twitter howled, and she backtracked.

As the street fight has played out, it has felt at times as if the choices for the roadway are a reductive binary between parking spots and sheds. What about the other things we could be putting in that space, like the “dynamically priced” ideas Doctoroff ventured in his Times op-ed? Meera Joshi, the deputy mayor for operations, is in charge of a new task force that removes abandoned and “egregious” structures. So far, the city has knocked down just over 100, making space in theory for … something. When we speak, she sounds wistful about the possibility of non-parking, non-shed curb space and talks about bike storage, containerization, art exhibits, and other dreams. That doesn’t mean any of it will happen. “Now, my saying it — I wish it was that simple to make it true. We can’t flip the switch that easily,” she says.

We’re likely to be in streetery purgatory for quite a while. According to a version of the legislation that began circulating this fall, restaurants could be given as much as a year to clear out their existing structures after the permanent program is approved.

In the meantime, most restaurants will do, well, nothing. Zhao now has a fence made of roll-up wire mesh to secure her space at night. “It’s simple and functional, doesn’t look great,” she says. She won’t make any more moves until she learns how long the city will allow sheds like hers to stay up.

John Tymkiw, a tall, floppy-haired Stuy Town resident, is probably the city’s foremost streetery devotee. A freelance creative director who once ran an art gallery, Tymkiw has turned into a kind of shed flâneur traversing the city to photograph them. He has collected his images in How We Ate, a three-volume, zine-style photo book that sells at the Whitney Museum store.

“I’ve kind of become an insane person,” he says. “I ride around the borough taking pictures. My wife and I are walking down the street and then it’s, ‘Hey, wait …’ What I’m trying to capture is the spirit — both the positive resilience of New Yorkers in tough times and also the creativity.”

Tymkiw is adept at crafting typologies and noticing ingenuity and weirdness. He categorizes planters as “innies” or “outies” depending on whether they sit in the street or not. He points out insets and hatches that accommodate Con Ed manholes. In the East Village, he says, 7th Street Burger’s ratty white structure is possibly one of a kind; the roof slopes the wrong way, toward the sidewalk instead of the street, funneling rainwater onto pedestrians. Its purpose, he figures, must be advertising: The tall streetside wall features big red letters that bear the restaurant’s name. Like everyone else, he doesn’t know what to call sheds either.

By photographing them, he hopes to freeze the sheds in time as singular, positive relics of the dark COVID-19 years. “After all the bullshit everyone is arguing about and all the tragedies, the way people suffered, when we look back on this era, is this the one good thing people are going to remember?” he asks. For a long time, Tymkiw pondered, What makes a shed good? Eventually, he decided to evaluate them the same way he did a work of art. They’re good if you can look at them more than once without being bored.

*Correction: City Hall has reportedly held up a proposed 5.4-mile bus lane in Queens. A previous version of this story referred to it as a bike lane.