When people walk into Paul Goldberger’s new apartment for the first time, they gasp. A wall of windows 45 feet wide seems to hang over the East River, offering a view of at least three miles of the Queens and Brooklyn waterfronts. Between the Queensboro Bridge to the north and the Williamsburg Bridge to the south is a skyline made for an architecture critic. In the near distance on Roosevelt Island are the Cornell Tech campus, with buildings by Morphosis and Weiss/Manfredi, and the Louis Kahn–designed Four Freedoms Park, which Goldberger considers a masterpiece. Farther east on the Queens and Brooklyn shores are Steven Holl’s controversial Hunters Point Library, “yin and yang” apartment towers by OMA New York, and PAU’s new office building inside the old Domino Sugar plant, all of which have risen in the past few years. Goldberger, a Pulitzer Prize winner, could deliver a lecture on the state of contemporary architecture from his living room and not need slides.

There’s also the river. His view from the eighth floor at 870 United Nations Plaza includes as much water as land, and it’s mesmerizing. “Fifteen minutes of looking out the window is like an hour of therapy,” he says. “And cheaper.”

Along with the views come the windows that frame them — part of an elegant dark curtain wall comparable to those of Lever House, by Skidmore Owings & Merrill, and the Seagram Building, by Ludwig Mies van der Rohe, two acclaimed glass office towers from the 1950s. U.N. Plaza, Goldberger says, “isn’t Mies, and it isn’t even SOM. But it’s as close as we’re going to get in a residential building in this city.”

For Goldberger, a lover of modernist architecture and architectural history, 870 U.N. Plaza and its twin, 860 U.N. Plaza, offer lots of both. The 39-story towers, rising from a shared six-story base, were designed by Max Abramovitz of Harrison & Abramovitz, the firm that coordinated the design of the United Nations campus by Le Corbusier, Oscar Niemeyer, and others. Early drawings by Abramovitz show two unadorned slabs forming the northern border of the United Nations site, as if anything fussier would have been a distraction from the near perfection of the General Assembly and Secretariat ensemble. Abramovitz must have been happy that a 1929 plan for the U.N. Plaza block, featuring an ornate building by Rosario Candela called Water Gate, had succumbed to the Depression.

The 336-unit complex, completed in 1966, fills the entire block between 48th and 49th Streets from First Avenue to the FDR Drive directly north of the United Nations. Goldberger believes it deserves landmark status. And he’s not just saying that because he lives there now. In 1979, while writing for the New York Times, he placed it on a list of the top postwar apartment buildings in the city. U.N. Plaza, he wrote back then, “has taken on a cool, established air, rather like that of a discreet and solid Park Avenue building.”

He is not alone in his enthusiasm. When he moved to the complex last August, Goldberger joined a number of resident architects and architecture buffs, many of whom are also recent arrivals. The group includes Jon McMillan, the senior vice-president and director of planning for TF Cornerstone, who has overseen the design of 12 towers on the Queens waterfront. After decades in the West Village, McMillan bought a one-bedroom apartment at 870 in early 2022 with his partner, the author and philosopher Jim Holt. Though he can’t see any of the TF Cornerstone buildings from his north-facing unit (“unless I stick my phone out the window”), he can when he enters and leaves the building. For him, that was part of the draw of U.N. Plaza. “I very much liked the idea of being able to look over at what I’ve been working on for the past 24 years,” he says.

During a recent visit to Goldberger’s apartment — the two are friendly — McMillan pointed out his contributions to the view, starting with the seven buildings of Queens West, one by Handel Architects and six by the Miami-based firm Arquitectonica, the tallest of which bears a giant “TFC,” TF Cornerstone’s logo. (“There is a tradition of big signage in Long Island City. It has always been about getting Manhattan to look across the river,” McMillan says.) To their right are the five TF Cornerstone buildings of Hunters Point South. Though Goldberger isn’t enamored of all the new high-rises, he likes the general effect, especially at night when, he says, thousands of lights twinkle. “Twenty years ago,” he says, “this would have been a very boring view.”

Another recent arrival is Aaron Schwarz, a former principal at the global architecture firm Perkins Eastman, who now runs his own small firm, Plan A. Schwarz and his wife, the art historian and curator Susan Hapgood, were looking for a change from the Chelsea brownstone they had lived in for 35 years. Hoping for a water view, they first considered co-ops on Riverside Drive. But after a couple of failed offers, they turned their attention to U.N. Plaza. For their two-bedroom apartment, Schwarz says, “we spent less than what we would have on the Upper West Side and far less than we sold our place in Chelsea for.” Their south-facing apartment on the 19th floor of 860 — the western tower — faces the sleek slab of the Secretariat, which Schwarz says is one of his favorite buildings in the world. Their view continues south to the unrecognizable-from-five-minutes-ago downtown Brooklyn skyline.

Schwarz is also a fan of the building’s Mad Men–era lobby, a double-height space with what seems like acres of red carpet. “When you walk into the building, it’s as if you stepped back into the 1960s or ’70s,” Schwarz says. But now residents are discussing the possibility of removing at least some of the red carpet — which has become almost a trademark — to expose the lobby’s original terrazzo floor.

Ben Cheney, who moved to U.N. Plaza in 2018 with his wife and two young sons, is in favor of the change. After examining several 1960s photos of the lobby, he believes the floor includes a trio of black rectangles, also terrazzo, representing the two towers and their six-story base. But removing the carpet is “a very controversial idea,” he admits. “People have crucified me for even suggesting it.”

Cheney is not part of the design world, but he says he is “obsessed” with U.N. Plaza “the way some people know everything about baseball.” For the past three years, he has run a rabbit hole of an Instagram account, @thelegendaryunplaza. He began it from California, where he was waiting out the pandemic, because he missed the building and decided to learn more about it.

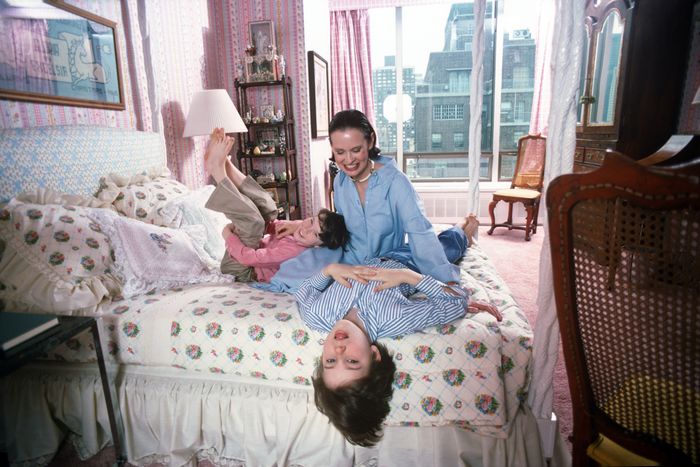

Many of Cheney’s 1,000+ posts focus on famous residents, including Truman Capote, the owner of 22G from 1966 until his death in 1984. A portion of the recent miniseries Feud: Capote vs. the Swans was shot in the red-carpeted lobby, and in one episode, Babe Paley worries that Capote is “rotting away like the prisoner of U.N. Plaza.” In the 1970s, Gloria Vanderbilt lived in a south-facing apartment and used a separate north-facing apartment as a studio. Johnny Carson, Walter Cronkite, the photographer Gordon Parks, legendary Condé Nast editorial director Alexander Liberman, and The King and I actor Yul Brynner were also residents. Cheney is fascinated by the apartments with magazine-ready interiors, at least nine of which have appeared in Architectural Digest since 1971. A duplex outfitted by the late, great architect Paul Rudolph for Henry Kaiser, an industrialist Cheney calls “the mid-century’s Elon Musk,” and his wife, Alyce, appears multiple times on the feed, as do two apartments by the famed interior designer John Saladino.

One loyal follower of Cheney’s Instagram account is the author Michael Gross, himself a chronicler of high-end Manhattan real estate (with books on 740 Park Avenue and 15 Central Park West). Gross and his wife, Barbara, moved to a two-bedroom at U.N. Plaza in 2015. He calls it “the best-kept secret in New York.” The staff is so helpful, he says, “it’s one step short of assisted living. And the cast of characters is incredibly diverse because apartments range from one-bedrooms to sprawling duplex penthouses.” He, like Goldberger, thinks highly of U.N. Plaza’s design. “In every aspect except an overabundance of limestone,” he says, “it is comparable to the best prewar buildings in the city.”

It isn’t Goldberger’s first time living in a distinctive building. “I’ve had a very fortunate real-estate life in New York,” says the youthful 73-year-old as he settles into a purple sofa in his living room. In 1976, he bought his first New York co-op, a one-bedroom in the Dakota — yes, that Dakota — for $42,000. He was able to trade up as he married and had children, moving first to the San Remo and then to the Beresford, the prewar landmark designed by Emery Roth at 81st Street and Central Park West. There, in a nine-room apartment overlooking Central Park, he and his wife, Susan Solomon, raised three sons. But when Solomon, a lawyer who went on to launch the New York Stem Cell Foundation, died in 2022, Goldberger began thinking of leaving. At first, he worried he would be abandoning memories of Susan and their 27 years there. But, he says, “I realized that if you have treasured memories of a place and a time, sometimes it’s almost better to move on, to close the book and hold on to it, instead of trying to add another chapter.”

Goldberger thought about going downtown but quickly discovered, he says, that “downtown is overpriced, and I’m overaged.” When he widened his search, his broker, Tim Malone, took him to see the three-bedroom unit that is now his home. He fell in love with its proximity to the East River. “In all the places I’ve lived,” Goldberger, who also has a house in Amagansett, says, “I’ve never looked directly out at water.” He was also amazed by how much he liked the apartment’s clean but not spartan décor, which he later learned was the work of designer Alexandra Champalimaud for the previous owners: Nancy Novogrod, the former editor of Travel + Leisure, and her husband, John, an attorney, who were moving to their house in Connecticut. (Wendy Goodman wrote about their apartment for this magazine in 2018.) Goldberger made just a few changes, adding shelves for his thousands of architecture books, matching the ones Champalimaud had done for the Novogrods a few years earlier, and installing new sunshades to protect both people and his works on paper. The latter include a drawing by Kahn of the synagogue he designed in Chappaqua and a Frank Gehry collage of his house in Santa Monica, along with pieces by Josef Albers and Ed Ruscha. Goldberger put a cardboard Wiggle chair by Gehry in the living room and worn-leather chairs by Le Corbusier in the adjacent library, which doubles as a guest room.

A recent “salon” at which Goldberger spoke about U.N. Plaza’s history attracted about 100 residents to a vacant duplex on the 37th and 38th floors. One of the event’s organizers was Nikki Field, a Sotheby’s broker who has lived in 870 for nine years. She acknowledged that U.N. Plaza isn’t always an easy sell because some potential buyers think of Midtown East as terra incognita. “U.N. Plaza has always been location resistant,” she says. “But once people come and see the architecture and the services, I can usually capture them.”

True, it’s a half-mile walk through the unglamorous Turtle Bay neighborhood from the nearest subway station to the building’s dramatic entrance. But Goldberger doesn’t mind. The blocks between First and Second Avenues are filled with family businesses and homey restaurants that remind him of an older, gentler New York. “It’s the way neighborhoods used to be. There’s a mellowness to it,” he says. “I thought I was moving here in spite of the neighborhood, but I’ve actually gotten very attached to it.” Plus, he enjoys a few activities that don’t take him through Turtle Bay: walking on the new East River Waterfront Esplanade, which is rapidly knitting together, and taking ferries to explore new construction in places like Hunters Point and Williamsburg on weekends. All those things are making the East River less of a barrier and more of a connector, something like the Thames in London or the Seine in Paris. Having moved from west to east, he can almost feel it: Manhattan’s center of gravity is shifting.