Three months after Colin Jost and Pete Davidson bought a decommissioned Staten Island Ferry for $280,000, Jost stood on its deck like a triumphant captain as it was towed through New York Harbor to a temporary dock, where the press reported that it would be transformed into a floating “entertainment venue” that would someday be tugged to a permanent home (fixing up the engine was deemed an unnecessary expense for a bobbing club).

That ride was two years ago next month, and ever since, the 277-foot-long boat seems to have just sat. And sat. And sat. Locals living near the Staten Island dock told the New York Post they haven’t seen anyone working on it, feeding a story line of two hapless comedians in over their heads — a story line the comedians didn’t seem to mind. Davidson told reporters he and his castmate were very stoned when they bought the ferry, and hoped it “turns into a Transformer and gets the f— out of there, so I can stop paying for it.” Jost responded with an Instagram post that asked, “Is it worse that I was actually stone-cold sober?” alongside a plea to fans to come pay to see him do stand-up on the “Ferry Money Tour!”

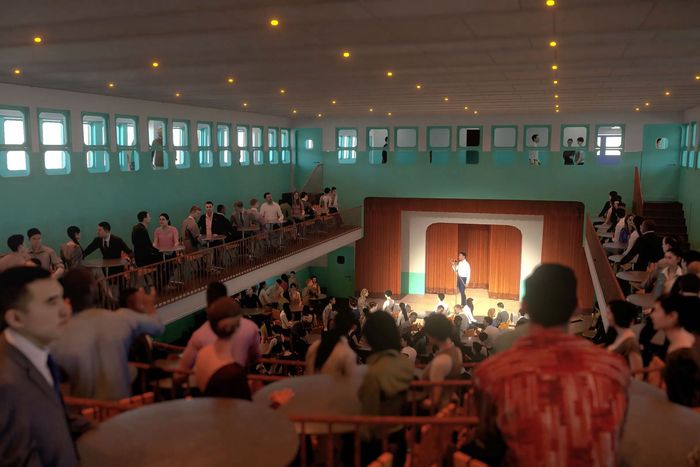

On a podcast last year, Davidson broke character and told Seth Meyers that there was an actual plan for the boat, regular conference calls about its redesign, and even renderings. “We had them do one of those computer-generated, show-you-what-it-could-be type things.”

But who was “them”? One report on the ferry purchase named a fourth partner, Ron Castellano, an architect who has worked for Richard Meier and Peter Eisenman. (The third partner, as has been widely reported, is comedy-club owner Paul Italia.) Castellano broke out on his own in the 2000s with renovations of historic buildings that retained their charm. He turned a former warehouse in downtown Brooklyn into a boutique condo and carved a newspaper office in the Lower East Side into 29 apartments, and is best known these days as the architect behind the Nine Orchard Hotel, which occupies a former bank off Canal Street.

On the website for Castellano’s firm, Studio Castellano, he listed the JFK Ferry as a project he was working on for the client “JFK Partners” with a budget of $34 million and a floor plan of 65,000 square feet. A short video that played on his website last month showed his renderings for each floor: a top deck furnished with patio tables set with umbrellas, another floor with two rows of hotel rooms that open onto sundecks, and a lower level with two clubs. Castellano says the venue is very much in the works — and may eventually open with two restaurants and six bars, whose aesthetics play off the style of the era the boat was built in, in 1965.

How did you get involved in partnering on buying a Staten Island Ferry?

I’m involved in a lot of strange things, where I try to buy lighthouses or helicopters or whatever. That’s just what I do. I have a collection of electric cars from the 1970s. But I couldn’t say I’m like a boat person or anything.

I had worked with Paul Italia. I’d known him from his venue in New York. I was literally with Paul when we were bidding on the ferry. And Paul had the connection to those guys. I don’t know when they came in — the next day, or whatever. I guess you could say he brought those guys in. Kind of a lucky circumstance.

Did you have a plan when you started?

We felt like it was cheap enough and we’d figure it out later. Since then, we’ve just been getting a plan together. I am taking the lead in the rehabilitation and design, and Paul will be lead in operations.

What’s Pete Davidson and Colin Jost’s role?

They have input. They see everything. We have meetings as needed, sometimes twice a week, sometimes every three months. Right now, honestly, I’m trying to get the design work done as fast as possible. So I’ll just go away and do my thing, present it. I’ve been working on the designs and working with consultants and the naval architects Persak & Wurmfeld and hospitality consultants and the speciality trades in that world, and we’re just moving forward.

So all these reports about the ferry just sitting there and you guys not having a clue what you’re doing are unfounded?

The things you read — I don’t even know what they’re about. I don’t even read them anymore.

On a podcast last year, Davidson said the ferry would have a restaurant, hotels, and a few event venues. Is that still the plan?

It’s going to have a lot of things. I think right now, we have six bars and two venues operated separately or combined. We have outdoor event space, we have restaurants — two restaurants. It’s a big boat, almost 300 feet long, 65,000 square feet. That’s one and a half times the size of Nine Orchard Hotel.

Davidson said it would have two hotels — is that still happening?

It’s only one floor of hotel rooms: 24 rooms on the fifth level. They have private sundecks.

But no pool? No cruise-ship vibes?

A pool is something that keeps coming up. We’re going back and forth. There’s little Jacuzzi kind of thing, but not a full-on pool. We’d have to do a floating pool.

You’re known for historic renovations that keep the character of the space. Is that how you’re thinking about the boat?

Yeah. For the outside of the ferry, the goal would be sort of like when you have a landmarked building, where you have to keep the exterior original and on the inside, you can do what you want. It’s not like we’re painting it blue. Conversion is the key word: We’re converting to another use, so you take what’s sort of special about the original and repurpose it.

We’re kind of taking clues from what’s there and from 1965, when it was built. It’s going to have the aesthetic of the original. It had a snack bar, beautiful bench seats. There’s baby-blue Formica and lots of pink. It reminds me of my elementary school from that same era. But when you get down to the engine room, it has that engine-room feel — which we can turn into a darker kind of place. We’re not going to trip it out with penny tile and awful fixtures — the stuff we see now in cruise ships. We’re taking what’s originally there and repurposing it. It’s still a work in progress, but it’s not going to be one of those awful casino boats.

You mean one of those dark boats with tinted windows and moldy carpets?

Yeah, exactly.

And Davidson said it’s going to go between Miami and New York City?

I think that’s exactly still the plan. It doesn’t have to be in one place. It can move, so we’re exploring both locations.

Exploring. So the locations aren’t finalized?

We have sort of the initial construction phase underway, like, we’re just bidding it out as it gets done. That’s going to take a year, and as that happens, we’re tightening the drawings, and as that’s happening, we’re going to find the location.

Ah. Does the location affect the design?

Yes, because we aren’t fixing up the engine and we plan to tow it between locations. And once you take out the propulsion system, it’s a floating barge, and that means it will be regulated like a building. So even though it was a boat, the Department of Buildings would have to inspect it.

So we will look at whatever local building codes oversee wherever it could possibly go. We’re going to different areas where we could dock it to see what the regulations there are. Most likely, if we park it in Miami, they’d inspect it and say it’s safe — but most of the time, if we’re safe in New York, we’re safe in Miami.

That sounds like so much to factor in. Is this why it’s taking longer than people expected?

I usually do buildings, but this is just like any project. If you never did a theater, you learn everything about a theater. So for me, I have to learn everything about a boat, but at the same time I have to bring on a naval architect. You have to deal with the fact that we’re taking a boat, which is a floating structure, and everything you’re putting into it is totally not meant for it, really. It carried cars and people and now it’s going to be a restaurant with bars and venues. So it’s nothing hard, it just takes time to figure it out piece by piece. It’s not like this hasn’t ever been done before, it just takes the time. But I spent 12 years on the Nine Orchard Hotel.

Twelve years would be a lot of time to pay to dock it — are you guys worried about that expense?

There’s no doubt it’s expensive to store. It’s 300 feet long, so it’s very hard to place. But to me, it’s nothing unusual. That’s what it costs.

I understand that if you dock in New York, you first have to get an environmental review. Is New York especially challenging to dock in?

The administration has been as helpful as they can be. We’re just not there yet, really. We’ve been working with the Economic Development Corporation, just trying to see if it makes sense. Because it’s going to hopefully draw 2,500 or 3,000 people wherever it can be. Or it could move — Staten Island would definitely want to keep it, and who knows where it would go. With any other development, the reality is — where are the most people who could use it? It would be great to keep it in Staten Island, but if it’s hard to get to and you can’t draw people, that doesn’t make sense.

And I think it’d be good publicity for Staten Island if it was somewhere else. The Staten Island Ferry goes all over the place here, so another one won’t make a big visual impact. But to have this giant orange ferry sitting off Miami or Tampa or North Carolina? It will have a bigger impact. It’s like taking a chunk of New York City and putting it somewhere else.

I keep hearing you say Florida. Is this definitely going to Florida?

There’s a lot of people having a lot of fun down there. But it’d be great to share it in different locations.

Up and down the Eastern Seaboard?

Exactly! Like a carnival.