A good idea can be a trap. The Japanese architect Shigeru Ban, a master of refined spectacle, once unfurled some bolts of fabric for an exhibition he was designing, then schlepped home the cardboard tubes. That pack-rat move — maybe they’ll come in handy someday — wound up shaping his career so completely that, four decades and a vast and varied portfolio later, he’s still often thought of as the paper architect — not because his projects remained on paper, but because they were made of it.

A new book that spans his 40-year career suggests that it would be more accurate to call him a paper, fabric, and wood architect. Or that his signature material is time. As a virtuoso of pavilions, temporary structures, emergency shelter, and post-disaster community spaces, he’s developed designs that are quick, cheap, and clean to build, radiate elegance for as long as they last, and can later be recycled. When an earthquake hit Japan in 1995, bringing down a church in Takatori, Ban replaced it with a Paper Church, an elegant elliptical colonnade inside a rectangular frame, topped by a tented roof. A crew of Vietnamese refugees erected it in a few weeks. After a 2011 earthquake destroyed much of Christchurch, New Zealand, he conceived a mini-cathedral in the form of a triangular pipe that widens toward the entrance and narrows toward the altar, making it appear longer than it is.

There are two keys to his approach to crisis. The first is the attitude that in times of disaster, beauty is a form of succor. The other is the humble paper tube, the kind that forms the core of toilet paper, duct tape, fabric, wallpaper, plastic wrap, and just about any rollable industrial material. Unlike other ubiquitous products — the shampoo bottle or the umbrella, say — the laminated cardboard tube has achieved a certain engineered perfection, making it lightweight yet strong, durable yet disposable, transportable, standardized, inexpensive, and — in hands like Ban’s — graceful. The tubes can be structural elements, just as steel beams, concrete columns, and wooden joists can. They can be bought off the shelf, efficiently shipped, and quickly assembled, even by a small and semiskilled team.

But early on, Ban saw that the tube isn’t just a component; it’s also an architectural form. A nave, a barrel vault, and a Quonset hut are all essentially tubes that can be stretched or truncated at any point. The essential quality is that the roof flows seamlessly into the walls. That was even true of the Nomadic Museum, which was erected on a Hudson River pier in 2004 to house an exhibition of overscale animal photographs by Gregory Colbert. The structure was a masterpiece of simplicity and drama: a basilica composed of stacked shipping containers with a central nave made of cardboard columns — tubes within a tube. At a more luxurious extreme, the centerpiece of Ban’s Swatch-Omega campus in Switzerland (the ideal project for an architect of time) is a long timber tunnel curved into a snakelike wriggle.

Among his heroes and collaborators is Frei Otto, the late German architect and engineer who wove steel cables into fantastical webs, as in the Olympic Stadium in Munich. Rather than fashion structural extravaganzas, though, Ban prefers to tweak simple geometries so they become fluid and complex. For the Centre Pompidou offshoot in Metz, France, Ban stacked three long rectangular galleries — tubes, really — at irregular angles as if they had fallen that way. But it’s the roof that steals the show: a wavy canopy made of white fabric stretched over a wooden frame. From the air it looks like a straightforward hexagon, from inside like a basket of interwoven stars of David, and from the side like a luminous Bedouin tent. That’s another aspect of time that permeates even much of Ban’s durable architecture: changeability, the impression that a building is constantly in the process of becoming something else. —Justin Davidson

The following excerpt is from Shigeru Ban: Complete Works 1985–Today (Taschen, July 2024).

Paper Church (Kobe, Japan)

Paper Tube Structure 08 was designed between March and July 1995 and built by 160 volunteers, essentially Vietnamese refugees, between July and September of the same year. It was a single-story, 168-square-meter building. This community hall and church was designed to replace the Takatori Church destroyed on the same site by the January 1995 earthquake. Corrugated polycarbonate sheeting was used as a skin and 58 tubes placed in an elliptical pattern, inspired by the church designs of Bernini, formed the structure. Operable glazed screens on the façade between the paper tubes allowed the creation of a continuous space between exterior and interior. The roof was made of tent material, allowing for some penetration of light during the day and a glow from the inside at night. The requirement that the church be easily assembled by non-skilled volunteers made Ban imagine that the structure could well be taken apart and used at another disaster site as required. Though made of apparently ephemeral materials, the church celebrated its 10th anniversary in 2005. Disassembled in June 2005, the church was rebuilt in Taiwan in 2008 with the same materials. It was replaced by a new Takatori Church (2006–07), also by Shigeru Ban.

Nomadic Museum (New York)

The Nomadic Museum was a 4180-square-meter structure intended to house “Ashes and Snow,” an exhibition of large-scale photographs by Gregory Colbert, on view in New York from March 5 to June 6, 2005. It was re-created subsequently in Santa Monica, California, and in Tokyo. No less than 205 meters long, the 16-meter-high, rectangular building was made up essentially of steel shipping containers and paper tubes made from recycled paper, with inner and outer waterproof membranes and coated with a waterproof sealant. Located on Pier 54 on Manhattan’s Lower West Side, the building had a central 3.6-meter-wide wooden walkway, composed of recycled scaffolding planks, lined on either side with river stones. The overall impression of this structure was not unlike that of a temple, or, as the architect wrote: “The simple, triangular, gable design of the roof structure and ceremonial, columnar interior walkway of the museum echo the atmosphere of a classical church.” The first building to be made from shipping containers in New York, the Nomadic Museum was an intriguing effort to employ recyclable materials to create a large-scale structure. Despite the rather difficult access to the site and high entrance fee, many New Yorkers went to visit Ban’s museum, perhaps more intrigued by its spectacular outer and interior forms than by the theatrical photographs of Colbert.

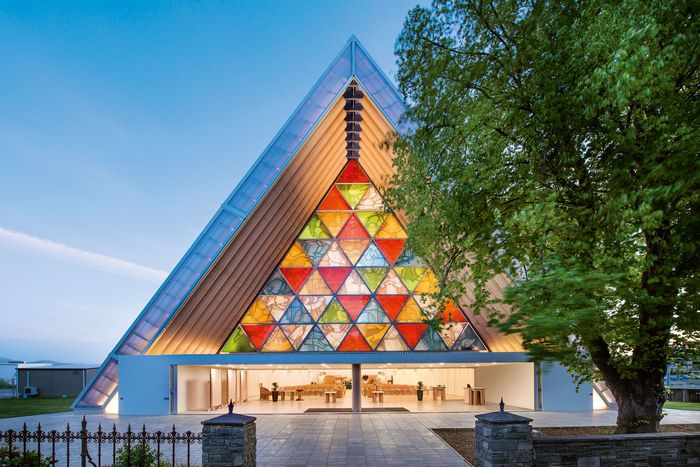

Cardboard Cathedral (Christchurch, New Zealand)

During the February 22, 2011, earthquake, 185 people were killed and more than 80 percent of buildings in central Christchurch were either destroyed or damaged beyond repair. The cathedral in the square was severely damaged, with its spire collapsing. Plans were made as of May 2011 to create a “transitional” cathedral in its place. Working as he has on other disaster relief projects on a pro bono basis (free of charge), Shigeru Ban created the transitional Cardboard Cathedral near the Canterbury Television site, where 115 people — including 13 Japanese students — died in 2011. Made with timber, paper tubes, polycarbonate sheeting, and ceramic printed glass, the Cathedral has a capacity of 700 people and, the architect explains, was made with “paper tubes of equal length and 6.1-meter containers forming a triangular shape.” Shigeru Ban continues: “Since the geometry was based on the plan and elevations of the original cathedral, there is a gradual change in the angle of each paper tube.” The 770-square-meter tentlike structure certainly assumes the role of the cathedral with grace. Its materials confer a certain modesty that is befitting of its religious function and, in a sense, typical of the architect. Shigeru Ban also designed 15 items of furniture for the cathedral including chairs, desks, music stands, donation boxes, candle holders, and bulletin boards using wood and paper tubes.

Centre Pompidou (Metz, France)

Shigeru Ban Architects (Tokyo) in association with Jean de Gastines (Paris) and Gumuchdjian Architects (London) won the design competition to build a new Centre Pompidou in the city of Metz on November 26, 2003. In this instance, Ban’s surprising woven timber roof, based on a hexagonal pattern, was the most visible innovation, but his proposal to suspend three 90 x 15-meter gallery “tubes” above the required Grande Nef (nave) and Forum spaces was also unexpected and inventive. Working at the time of the competition on the Japan Pavilion (Expo 2000, Hanover, Germany, 1999–2000; see page 200), Shigeru Ban purchased a Chinese hat in a crafts shop in Paris in 1998. “I was astonished at how architectonic it was,” says Shigeru Ban. “The structure is made of bamboo, and there is a layer of oil-paper for waterproofing. There is also a layer of dry leaves for insulation. It is just like architecture for a building. Since I bought this hat, I wanted to design a roof in a similar manner.” Ban was anxious to participate in the original competition because of the involvement of the Centre Pompidou, whose architecture he had admired as being audacious for its time. Aside from its spectacular interior spaces, the Centre Pompidou-Metz opens broadly onto its surrounding piazza, echoing the architect’s frequent interest in the ambiguity of interior and exterior.

Swatch/Omega Campus (Biel, Switzerland)

The first Omega watch was made in Biel/Bienne in 1894. Long installed in that city, on the bank of the Suze River, Omega officially became part of the newly created Swatch Group in 1998. Swatch launched a competition in 2010 to create a group headquarters on a site across the street from the older factories. Shigeru Ban won the competition by proposing several surprising variations on the Group’s requests for a total of three main structures. He imagined the Swatch building as a curving wooden grid shell covered partly with EFTE and partly with glass. Extending his design over a bridge that crosses the renamed Nicolas G. Hayek Street, Ban created a conference center on the roof of the entirely new Cite du Temps, which is otherwise dedicated to the exhibition of the Group’s products. By turning this new structure perpendicular to existing Omega buildings, Ban created a new public square, aptly named Omega Plaza. The Cite du Temps is 80 meters long and 17 meters wide. It has a floor area of 16,162 square meters, including five upper levels which are in good part a glazed, timber post-and-beam structure. The largest building of the complex, the Swatch Headquarters, is 240 meters long, 35 meters wide, and as high as 27 meters. Glulam columns and beams and cross-laminated timber slabs are the main structural elements of the building, which Ban describes as being “playful and colorful,” in keeping with the image of the bright plastic-cased production of Swatch. The timber and glass Omega Factory at the opposite end of the Swatch/Omega campus has an unusual concrete core that houses a sophisticated automated parts-retrieval system that serves the watchmakers within. The rectangular building is 70 meters long, 30 meters wide, and 30 meters high. Its wooden structure is submitted to fewer constraints than that of the Cite du Temps, for example, because of the solidity of the required concrete core. With this complex Shigeru Ban demonstrated a clear ability to navigate the complex issues not only of watchmaking in Switzerland, but also the corporate images of brands as different as Swatch and Omega — and he did this while showing that timber could be a main structural element in very different buildings.