This article was featured in One Great Story, New York’s reading recommendation newsletter. Sign up here to get it nightly.

Have you ever gone out drinking or cruising at the Stonewall Inn? Because it was the site of a queer riot set off by a police raid in 1969, it’s a landmark of LGBTQ+ liberation and easily the most famous gay bar in the world. But let’s face it, landmarks are for tourists — as is, as far as anyone remotely my age is concerned, the tony-yet-fratty West Village neighborhood where it sits.

But, in the spirit of Pride, I stopped by this past Saturday night. There were rainbow (plus bisexual, lesbian, trans, and asexual) flags everywhere, and upstairs the former Drag Race contestant Brita Filter was performing in front of a cardboard cutout of RuPaul for a crowd of stubble-faced boys in khaki shorts. Unfortunately, her surprisingly melancholic lip-sync to “Try a Little Tenderness” was ruined by two evidently overserved, almost certainly straight girls screaming for more Nicki Minaj (unlike everyone else in the room, they didn’t tip). Downstairs, a twinky bartender in his skivvies was carrying a tray of shockingly strong Jell-O shots around the room. In the back is a merch stand; the attendant told me he was hired specifically to keep up with demand during June. His record is selling $2,000 worth of T-shirts on a single night. The place feels a lot like a happy, tipsy, rainbow-America tourist trap.

Which, you know, my snobbery aside, isn’t so bad. “Espresso” was blaring over the speakers, and over the course of a couple of hours, I had a terribly good time playing the local to the out-of-towners, many of whom told me they had come to drink here after a day tromping across the Brooklyn Bridge or ferrying to Staten Island. Many of them had European accents and said they were staying at various Marriotts and Hilton Garden Inns around town. It was on their New York bucket list. My favorite was a gaggle of cute queer girls from Taiwan who were visiting for a business conference and very much looking forward to stumbling to “Carrie Bradshaw’s apartment” next.

At the bar, I got to talking to two women I took to be a couple in their late 30s, the femme one holding a Bergdorf Goodman bag, the butch in a breasty tank top. I asked if they were together. ““Yes!” they squealed, before correcting themselves. “No! Wait! We’re just besties. We’re on a girls’ trip, and we’re both married to men who would never come into this bar.” They tried to gently assure me they weren’t homophobes like some of their neighbors back in Iowa. As they explained, slurring, the butch’s aunt was a lesbian, which is why these two straight ladies from corn country came to pay their respects. They bid me farewell with a chipper “Happy Pride!”

But it wasn’t all eager allies. There were plenty of young queers soaking in the bar’s provenance and reliably stiff pours. “I’ve got tequila shots from the bar and blunts in my bag,” a trans girl named June from Jersey called out to me on the way back to a table with her friends. On my way out, the merch attendant told me about an experience he had had earlier that day, when an older man from Long Island came in with a younger boy. He was not, as the attendant first assumed, a daddy, but rather an actual father with his actual son. “He said, ‘My son came out a few weeks ago. He kept it from me because he thought I’d hit the roof. I’m showing him his history.’” (Full disclosure: one of the only times I’d previously visited Stonewall was to take a photo with my own eager-ally parents.)

To be clear, the Stonewall Inn at 53 Christopher Street is sort of a modern replication. The original bar closed a few months after the riots, and the space, which also included the storefront of 51 Christopher next door, was divided. Over the years 53 Christopher Street became a bagel shop, a Chinese restaurant, and a men’s clothing store. In 1990, it opened as a gay bar called New Jimmy’s. When the owner, Jimmy Pasano, died of HIV/AIDS, it was finally renamed Stonewall. In the meantime, its once bohemian neighborhood gentrified (there were a number of complaints about the bar being infested with drug dealers) and it nearly shut down.

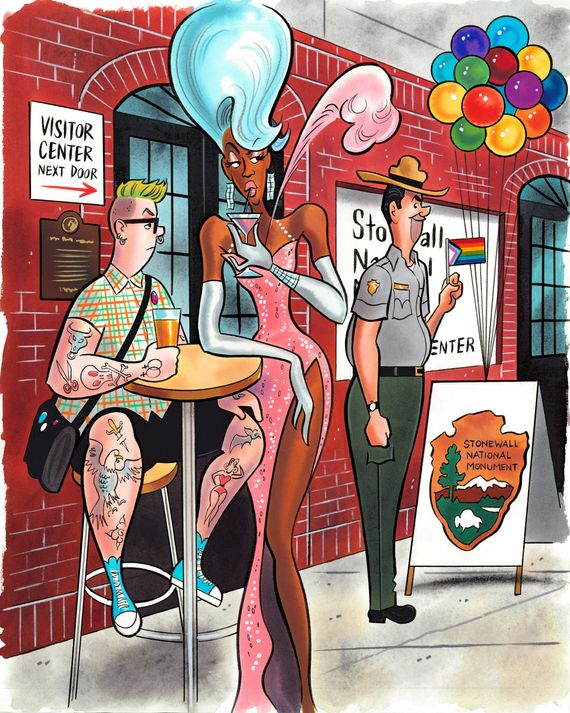

On June 28th, the 55th anniversary of the riots, the 51 Christopher Street half of the original bar’s footprint is going to open as the official Stonewall National Monument Visitor Center, which will be operated by a nonprofit called Pride Live for the National Park Service. There will even be actual Park Rangers (but not, unfortunately, in modified, Tom of Finland-style uniforms) whose jobs will include educating visitors about the riot’s contested history. The storefront most recently housed a nail salon, but back in the day, it was also the Stonewall Inn.

But the two halves of the original whole are not in any way affiliated — or, as I discovered, even cooperating with one another. And the bar’s owners, who saved the place from going out of business in 2006 and consider themselves stewards of its legacy, are in the dark about what’s happening next door. The visitor center’s press release notes that one of its goals is to “reunite the space of 51 Christopher Street with its legendary neighbor, the Stonewall Inn.” Now they seem like uneasy neighbors: one serving shots and a good time, the other serving a somewhat sterile history lesson underwritten by some corporate sponsors. At a time when the right is again on the march against queer rights, its somewhat tidy vibe can feel like something out of the Obama era. The visitor center has even chosen to spotlight a bricked-up archway that used to join the two halves of the gay dive bar where history was made. But that portal to fun is sealed up tight.

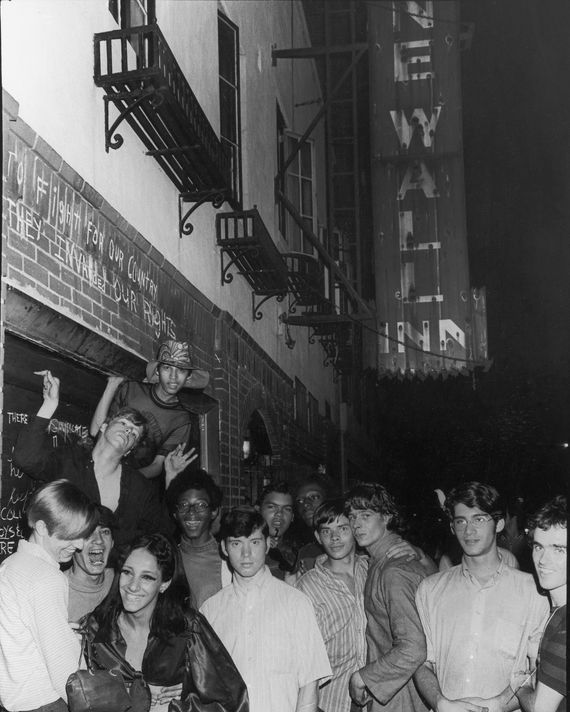

Back in 1969, when same-sex behavior was illegal, the Stonewall Inn was run by the Mafia. They had a deal with the NYPD. The police raided the bar and harassed the clientele frequently, but usually the Genovese crime family would just pay them off. “It might’ve been dirty. It might’ve been a dive bar. It might’ve had watered down drinks,” Mark Segal, 73, who was there the night of the raid, told me recently. At the time, he was new in New York. “I was a typical 18-year-old, and as an 18-year-old, what do you want to do? You want to dance.” The Stonewall Inn had the only dance floor in the neighborhood.

It was the late sixties, and uprisings, marches, and revolts of all kinds were breaking out all over. Radical change was being demanded. Segal — “It was until that night that I was a typical 18-year-old” — helped found the Gay Liberation Front, which organized the first Pride march a year later.

“We’re the only movement where the movement was born in a bar. But it’s way more than a bar,” says Stacy Lentz, who, together with Kurt Kelly, Bill Morgan, and Tony DeCicco raised the money to take the bar over in 2006. “People come in and cry as soon as they walk through the doors,” she says. “I think a lot of people sense the freedom.”

In 2006, “the history was not that well known. It was certainly not a place where people in the community gathered,” she says. “A lot of people just didn’t care. You have to think of where we were: still five years away from getting gay marriage in New York.” Soft-spoken and curly haired, Lentz, 54, is drinking a co-branded Stonewall Inn IPA from Brooklyn Brewery. She grew up, she says, in the “cornfields” of Kansas, just 40 miles from where the trans man Brandon Teena was murdered in 1993. She remembers when that happened; it helped lead her to activism, which now includes making sure Stonewall doesn’t end up another Starbucks or a Chase Bank (She also runs an associated nonprofit, the Stonewall Inn Gives Back Initiative).

The bar has followed the mainstreaming of its story since then, including Barack Obama’s name-checking it in his second inaugural address in 2013 and Roland Emmerich making a kinda awful movie about it in 2015. Taylor Swift and Madonna staged surprise performances here in 2019, and last year, Vice-President Kamala Harris stopped in for a photo-op (if you don’t remember the resulting viral moment, Andy Cohen made her dance to “Padam Padam”). When the pandemic almost did the bar in the way it did in so many bars and restaurants, it was saved by a GoFundMe and its corporate sponsors, including Estée Lauder, jetBlue, and Saks Fifth Avenue.

And now, four years later, it has a new neighbor. They’ve taped a grumpy paper sign on the entrance: “THIS IS THE STONEWALL INN. THE VISITOR CENTER IS NEXT DOOR.”

So what is going on next door if you can’t get Jell-O shots?

Back in 2016, less than two weeks after the Pulse nightclub shooting in Orlando, President Obama declared the 7.70-acres including and surrounding the bar the Stonewall National Monument (also in that category: the Statue of Liberty and Federal Hall.) Attaining national monument status meant it would now be under the protection of the National Park Service, which set out to build an official visitor center. As a press release notes, “We hope it stands as an enduring and resilient symbol and serves as a beacon for generations to come, providing the unique opportunity to step foot on the site where history unfolded and where the fight for LGBTQIA+ equality was ignited.” Needless to say, it is the first “LGBTQIA+ visitor center” in the National Parks system.

The completion of the center is thanks mostly to Diana Rodriguez, an activist who’s worked for GLAAD, the Clinton Foundation, and now runs the nonprofit Pride Live with her spouse, Ann Marie Gothard. They raised over $3.2 million to complete the project in part by courting high-profile “corporate partners,” including JPMorgan Chase and Amazon.

Back in May, I was invited to take a tour around the center with Rodriguez. “To be the first LGBTQ visitor center within the National Park Service I think is really important,” she told me when I arrived, “because I don’t think when people think about the National Park Service, they think urban, they think subway, they think queer people of color.”

The build-out was still in progress, but she tried her best to explain her vision.

One of the first things you’ll see when you walk inside is a quote from President Obama: “From this place and time, building on the work of many before, the Nation started the march — not yet finished — toward securing equality and respect for LGBT people.” (To read his full commemoration address, simply point your iPhone toward the QR code on the wall.) It’s arguably a curious decision, considering that the former president is, um, straight and recalling that it was then-Vice-President Joe Biden who came out in support of same-sex marriage first. Rodriguez calls this the “Why Wall,” and next to it was an empty space that she told me would soon become a “Google activation,” using a word I’m more used to hearing in the context of a branded Fashion Week party (I later asked what became of it. Apparently, it “features digital screens that convey the impact of Stonewall’s legacy around the world and spotlights the voices of revolutionary hope”). There’s also an American flag which once sat on her uncle’s casket; he was a Vietnam veteran and died of HIV/AIDs in 1989.

Up next was — here’s another word one is more likely to hear in an influencer-y context — the “content story wall,” which includes a special section devoted to the riot’s most famous participants, Marsha P. Johnson and Sylvia Rivera — “If you ask 90 percent of people ‘What do you know about Stonewall?’ they’ll say those two names,” Rodriguez says — and gives a (very) brief history of queer life in Greenwich Village. “In a time of just scrolling, I want people to pause and understand what happened here,” Rodriguez told me. “One of the things we’ve tried to do with the content is make it take-away content.” There’s also a jukebox, “the same type that was playing the night of the rebellion, a 1967 Rowe AMI,” that will shuffle a playlist curated by Honey Dijon. It includes the only song Segal remembers listening to here: “Aquarius/Let the Sunshine In” by the 5th Dimension.

Elsewhere in the quasi-museum is a piece of art by a 21-year-old trans NFT artist named FEWOCiOUS and an “exhibit” curated by students at Parsons which is meant to explain “what Stonewall means to them.” Of course, there will also be merch for sale. “When you’re wearing the merch, it’s another way to identify,” Rodriguez tells me. You can also get your passport stamped.

The back half of the center is designated for a “theater” surrounded by golden shovels embedded in the walls, each displaying a name of one of the sponsors, including Google, Hudson Yards, Adam Lambert, Christina Aguilera, Booking.com, and the AARP. Rodriguez’s publicist chips in that Donatella Versace has also been “very supportive.” They are clearly proud of their fundraising skills: “Who wouldn’t want Google as a partner?” Rodriguez asks me. If anything, the center might be proof that “rainbow capitalism” lives on — at least for now — even after last year’s debacle about pronoun knickknacks at Target and the Bud Light boycott.

Rodriguez notes that the windows are made of riot glass among other security precautions. Which makes sense: the State Department has issued a warning about possible “terror attacks” targeting Pride events around the globe this year; Christopher Park across the street was vandalized just last week.

It’s clear that in heading up this visitor center Rodriguez and Pride Live are trying to offer their own interpretation of Stonewall’s legacy. Outside, a neon sign, which features the center’s “pledge” — “In the name of those who came before me, I pledge to be brave, to be true to myself, and to fight like hell for equality” — has been installed, and it dares to outshine the Stonewall Inn’s own neon sign next door. Out on the street, the Christopher Street 1-train station will soon be renamed the “Christopher Street–Stonewall National Monument station.”

“Stonewall belongs to no one in particular. It belongs to everybody,” Rodriguez tried to assure me. “Everyone has a right to put forth their feelings.”

It’s true that interested parties have long bickered over what happened that first night at the Stonewall Inn. Who threw the first brick at the cops? Despite popular belief, it wasn’t Sylvia or Marcia but perhaps a butch lesbian named Stormé DeLarverie. Was it even a brick? Possibly, but some witnesses have referred to it as a cocktail glass, a rock, or a Molotov cocktail. Rivera tried to debunk one of the more enduring myths, that the riots were brought on by the death of Judy Garland. Others have claimed that Rivera wasn’t even there. “I didn’t want to get involved with all the people who use Stonewall for political reasons or fiefdom reasons,” Segal had told me. “What you have to realize is that these were serious riots. Is anyone taking a roll call?” He reiterated something Rodriguez said: “No one person’s story is the complete story of Stonewall.”

I’d asked Segal, who created the “content wall” for the visitor center, about the last time he went into the bar itself. He calls it “the reproduction Stonewall.” “My picture is on the wall,” he told me. “But I don’t feel anything when I go in there.” Which is a shame, because I left the visitor center feeling the same way. If the bar feels like walking into a messy, somewhat cheesy thing that was once part of an outsider culture constantly on the edge of being raided by the cops, the visitor’s center, with all its gender-studies good intentions, hardly feels alive at all.

Postscript:

On another night this Pride, I met up with another man who’s made a career talking about Stonewall. His name is Tree Sequoia, and he is 85 years old, over six feet tall, and has bartended at numerous incarnations of the bar. Until recently, when he got two knee replacements and broke his back. He was also there on the night of the riots, dancing the Lindy Hop with his friends Charlie and Bubbles.

We were meeting at the gay Chelsea sports bar Boxers and Tree was struggling to hear me over the pop music blaring out of the speakers, at one point growling, “There’s nobody here! Lower the music!” Drinking a vodka-cranberry, he politely held court while boys and drag queens stopped by to say hello to the man they call “Dad” or “Granny” or “Aunty Oak.” He goes by Tree, he explained to me, because he grew really fast during puberty, and his friends used to call him Tree Top (“Is he top?” I ask. “Always”). These days, he plays the role of dirty grandpa, and he entertains me with countless naughty jokes about his time growing up gay in New York. “I’m the only altar boy to ever be sued by the priests. ‘Come here father, it’s not a sin,’” he cracks at one point, doing a sexy “come hither” gesture. Often, when a youngster passes our table, I catch him sneaking a look at his ass.

I asked him about the riots. He had a blast. “I was a good kid all my life, and there I was throwing bottles, rocks, setting garbage cans on fire,” he says. He tells me about how he used to go to jail “all the time” for being in gay bars, but also about the times he’d sneak into neighboring buildings in the Village after going out to have sex on the rooftops. “I would blow you, you’d keep a look out,” he remembers. “You’d blow me, I’d keep look out.”

Over the years, he’s become something of an ambassador for the Stonewall Inn. On the 50th anniversary, he traveled to 13 different Prides around the country in a single month. While manning the bar, he learned to say “Hello, how are you?” in 15 languages, and he proves this to me by showing off in Chinese, Japanese, and Dutch. “The tourists throw money at me,” he says.

At the end of our drinks, Tree hobbles up onto the stage and lip-syncs to Al Martino’s “I’ve Gotta Be Me,” his elder queen version of “Born This Way.” “Are you going to pole dance next?” I asked him, pointing to a pole in the bar across the room. “When you find a pole with a cock this big,” he shoots back, miming a big one.

He is a living, breathing, vulgar history lesson, and it occurs to me that if all the caretakers of Stonewall would cooperate with one another, he’d make an excellent Park Ranger.

Tree doesn’t care, though. He has his own plans on leaving his mark. “When I die, my ashes are going in the park across the street,” he told me. “So if you see a cute boy, and he has something in his eye, that’s me.”