Alexander Girard’s textiles, his designs for Herman Miller, his restaurant design for La Fonda del Sol in New York, and his interior design for J. Irwin and Xenia Miller Miller’s house in Indiana, with its sunken living room, are some of his most notable contributions to the design world. They are also just a few of the more than 800 illustrations and photographs in Alexander Girard: Let the Sun In, Todd Oldham and Kiera Coffee’s upcoming monograph on the designer, many never seen before. The book is both a tribute to Girard, and a whistle stop through everything he touched, including tours through all his personal homes, beginning with his bachelor pad in Florence and winding through the homes he shared with his wife, Susan, in Grosse Pointe, Michigan, New York City, and, finally, their last home in Sante Fe (which was just restored and put on the market). Girard was prolific to a “near alien” degree, according to Oldham.“I honestly don’t know how any mere human could have possibly achieved all he did,” he says. But the designer was far from precious about his work. Interiors, in his view, were living, breathing, morphing spaces — or, as he put it,“a slow-motion movie of junk changing position.”

In 1937 Alexander Girard and Susan moved to Grosse Pointe, Michigan. They lived in a small apartment while renovating a home nearby, eventually moving to this residence on Lakeland Avenue in 1944. Four years later, the Girards moved to their second Michigan remodel, this time on Lothrop Road. In this home, Girard addressed two older structures by connecting them with a central building. The new volume became his family’s common area, and the bedrooms and personal spaces were in the older structures. Girard showed a lot of energetic experimentation in both Michigan homes. He placed textured furnishings alongside spare, modern pieces, finding a unique balance. In his Lakeland Avenue home, he painted a vivid mural on a staircase wall that was not far from a seat upholstered with a South American textile. In the living room, he placed a few elegantly curved plywood chairs that he had designed. These had a lot in common with chairs Charles Eames had designed, and when the two first met, they were shocked at their synchronicity (which bonded the designers permanently).

Girard upholstered and reupholstered sofas frequently in his Michigan homes. He designed numerous storage solutions. He designed a cherry wood dining table that he blithely planned to sand down if it got stained. Everything felt up for grabs; Girard had more room than he had before, and he was eager, agile, and moving at full speed. The outdoor spaces on his Michigan properties were transformed by Girard’s innovative use of recycled materials. After a bit of demolition at his Lothrop Road, Michigan, address, Girard took the broken bits of leftover concrete and incorporated them into his yard surface, letting grass grow up between their edges. He took blocks of salvaged wood he had accumulated and built a rich outdoor wall surface out of them. It was strikingly beautiful. The collaged wood installation supported a rotating crop of objects that captured Girard’s interest (he later created a similar wall in Santa Fe, still toying with its possibilities). Each of Girard’s Michigan homes was rife with invention. Each included a few nascent ideas that arrived from his previous dwellings and got resolved here. Additionally, many new ideas began in Michigan and moved with Girard to his next home to complete their cycles.

The last two of Alexander Girard’s residences were in Santa Fe, New Mexico, where he and his family moved in 1953. His first property had two adobe structures that were more than a century old. He joined these together with a new construction and remodeled the older parts. His second Santa Fe home was across the street from his first (this was the property Girard would spend his last years in).

The city of Santa Fe was not yet an art-world destination in the 1950s. Girard said he moved there to have “the luxury of not being interrupted.” He absorbed the rich design of Santa Fe and fit it together with his own concepts. His designs evolved quickly, strikingly. A friend of his said, “Having seen the Grosse Pointe house, when I saw the ‘new’ Girard house in Santa Fe, I was amazed, to say the least, for this was a house built of timber, adobe, brick, and a few stones by the inhabitants of the region. Just what was Girard trying to do? Had he lost his senses? Had I misjudged him, and was he more of an eccentric than the normal person that I supposed? I was momentarily lost.” After experiencing the house a bit longer, this friend was won over and wrote this about Girard: “No matter what remote region he visits, he is sure to interpret and give new life to whatever he finds there, on contemporary terms. He is a master at neutralizing the contemporary design trend toward the theoretical and mechanistic, with human warmth and emotion.”

Girard designed lovely adobe benches for his Santa Fe homes, and built-in adobe tables and niches. Beams were left exposed. A sleek, modern staircase stood in contrast to the soft clay around it. Where Girard’s mantels in New York had been ornate, here they were plain, noble. Girard hadn’t left behind his love of ornamentation; he simply redrew it. He painted rich, detailed murals in a number of areas. Two of the larger murals had similar geometric designs and lived on opposite sides of the same wall — one in the dining room and the other outside in the courtyard. The inside mural was painted in cool tones, the outdoor mural in hot, saturated colors. A casual viewer might think Girard tended to adorn his interior spaces in muted colors, but another interior mural, all bright magentas and reds, would prove this theory wrong. Charles Eames said, “Uninhibited by conventional color schemes, designer Alexander Girard has used color in the same unembarrassed way that characterizes his approach to all design in the home.”

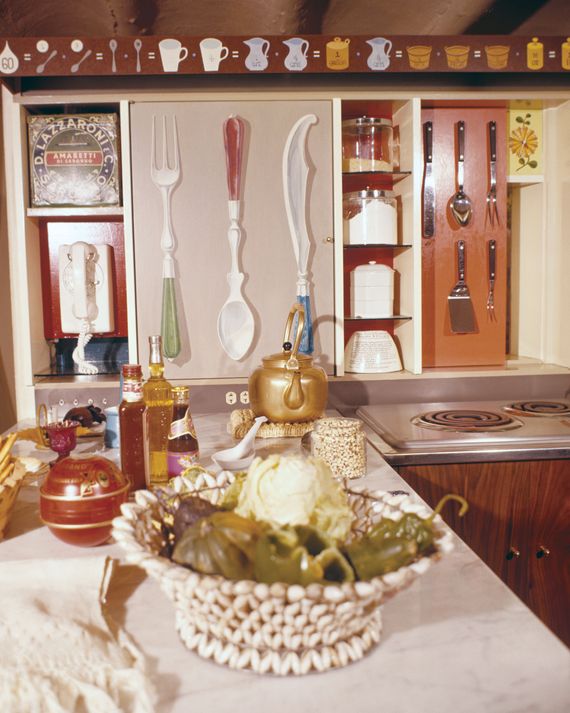

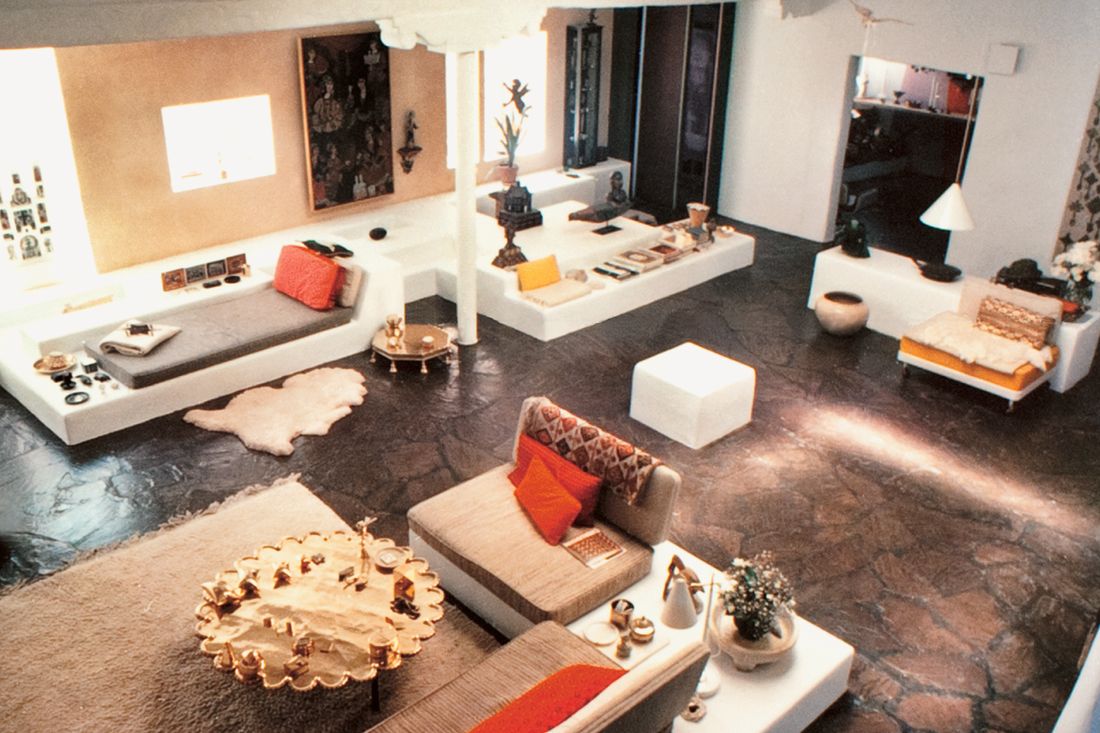

In the first Santa Fe house, Girard’s couch heights dipped lower than usual. He placed some sofa cushions at floor level. Pillows were abundant. Much like he would in his design of the restaurant La Fonda del Sol (possibly as a predecessor to that one), Girard erected a room within a room — which appeared as a large adobe cube — to encompass the kitchen, a unique space where argyles of tiny faux food were built into the cabinet structure beside other remarkable murals made of dried beans or showing measuring standards, bearing paintings of large utensils. Along the outside of the kitchen cube, Girard built niches of different shapes into the wall to accommodate his dog’s bed, a television, and a radio. His inventions were a mesmerizing combination of reverence (to the local design history) and playfulness.

In Santa Fe, as elsewhere, Girard designed everything in his sightline —things small and large. He designed and outsourced the making of custom light bulbs for his Santa Fe home, and beautifully intricate brass doors for one storage cabinet. He and Susan designed a garden that they calculated (correctly) would look wondrous when the snow fell. A low brass table from India lived perfectly in the decor of his Santa Fe home, as if it were born there. A snake clock curled very naturally on the wall (see page 361). But nothing remained static, as usual; Girard’s décor changed continually. Vogue published his first Santa Fe house three times in three years. This speaks of its merit but also its constantly changing guise. As consistent as any of Girard’s themes was his proclivity for reinvention.

Notably, Girard’s Santa Fe houses were where his folk-art collections flooded into his living spaces and took up full residence. He had long collected handmade things: folk-art sculptures, paintings, ceramics, candles, and more. In Santa Fe he came up with new ways to display his collections on custom shelves (freestanding and built-in): He placed them on beautiful, customized platforms in delicate niches and nooks. Without allowing his rooms to be overrun, his objects became a bigger part of his environment. Girard said, “The only important consideration is to force things to become part of your life rather than to allow yourself to become, so to speak, a part of things’ lives. That’s my point of view.” In one instance, Girard adapted the usually hidden building motif of studs covered by sheetrock to make shelves. Girard changed their usual measurements to fit his art objects and left the spaces open (without sheetrock) to serve as shelving.

The textile designer Pupul Jayakar said of Girard’s first Santa Fe home, “It is a reflection of a very vigorous and vivid mind — a mind that is capable of contracting and expanding — which sees that it’s not necessary to find an answer but to be. It is a house that is alive.” All of Girard’s homes were alive, as were those he designed for others. It was that very essence of life and rejection of a static existence that defined everything he created.

More Great Rooms

- The Water-Tower Penthouse in the Bronx

- Rosario Candela Invented the Upper East Side Apartment

- From a Downtown Loft to a Sutton Place Classic Seven