At a time when Park and Fifth Avenues, Sutton Place, and Gracie Square were the ultimate addresses of wealth and power, Italian American architect Rosario Candela designed the neighborhood’s most definitive buildings. Never flashy or ostentatious, these prewar buildings were elegant and discreet, clad in brick or limestone, with setbacks and terraces that afforded owners, especially those living near the top floors, private views of the sky above and the city below.

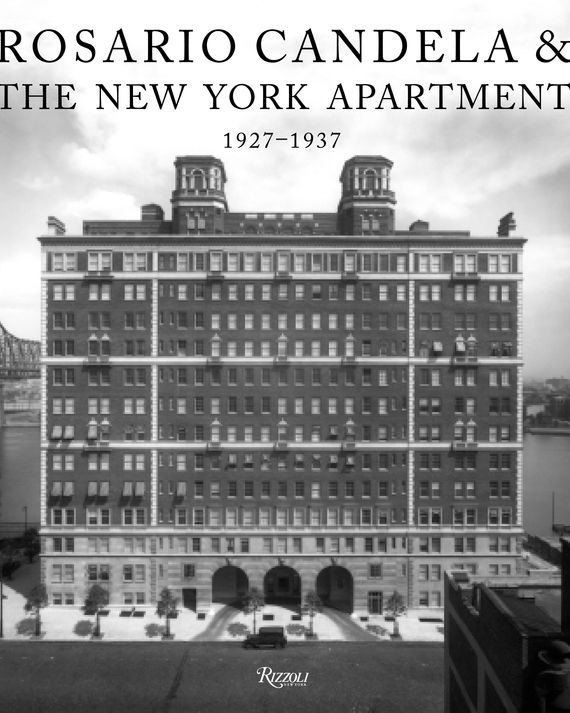

To this day, Candela’s work defines the Upper East Side’s architecture of luxury, and now — finally — comes a book that gives us not just a photographic record of Candela’s work but also essays on Candela by three design authorities: designer David Netto, architecture critic Paul Goldberger, and architect Peter Pennoyer. Using a breadth of archival material, Rosario Candela & The New York Apartment: 1927–1937 goes deep on 19 of Candela’s buildings, revealing how he brought luxurious layouts and grand-scale rooms to apartment living — like, for instance, a two-story staircase window in a penthouse at 834 Fifth Avenue.

The idea for the book began, says Netto, on the steps of the Museum of the City of New York on a spring evening in 2018. They had just attended a panel for “Elegance in the Sky,” an exhibition on Candela, and Netto was consumed by “the gnawing terror that someone else would do the book before me!” In his view, Candela’s story “was possibly the great untold story of New York, of the architect I have come to think of as the Bernini of the Upper East Side.”

Netto got Goldberger and Pennoyer onboard “and then held these very busy people to our pledge.” Eventually, they also brought in Takaaki Matsumoto to do the design, which included the tricky work of cohering all the different material between archival and current photography and floor plans.

It’s become a timely project for Netto. “The buildings are about to turn 100 years old; when, if not now?” he says. “I owed it to New York, too. New Yorkers love a great story — especially if it stars them.” — Wendy Goodman

It would be impossible to dream the dreams we have of New York without the architecture of Rosario Candela.

Candela’s apartment houses are the means by which we know the great residential neighborhoods of the Upper East Side and Sutton Place — the built environment by which they signify. They are the crown jewels of Park and Fifth Avenues. His legacy and somewhat mysterious genius as a designer have been examined with a growing momentum, beginning with the first mention of him, which I am aware of, in Paul Goldberger’s The City Observed (1979). In a few words, Paul captured the importance of their silhouettes in the visual landscape of New York, describing the towers of 770 and 778 Park Avenue as “great gateways to 73rd Street” — or, if viewed from the east, to Central Park. Coming across this citation of Candela in the New York skyline was a validation of my instincts as a young architectural historian; I had been walking by these buildings on my way to Buckley, the school I attended until 10th grade, on 73rd Street between Park and Lexington. As I made my way down certain blocks day after day, I found myself only looking up.

I knew why — because I was a nerd. But in one sentence, Paul’s observations made me realize there was something more to this. He gave expression to what I had noticed, that there was indeed something resembling another city up there, one I later came to call Candela’s “Second City.” The action started above the 12th floor, at the point many of his buildings set back from the lot line and start to terrace their way up to an enclosed water tower, and to my mind this fantasy town in the sky was much more exciting than the real city at street level down below. Like a Dead End Kid, but wearing a tie and a backpack, I looked up, mesmerized, and thought about the life that must be going in apartments like those. As it turns out, I was right about all of it. But other than that one sentence by my fellow contributor to this book there was nothing else to read and nowhere to learn more. I had to find another way to learn about buildings than from books, and that came in the form of reading plans.

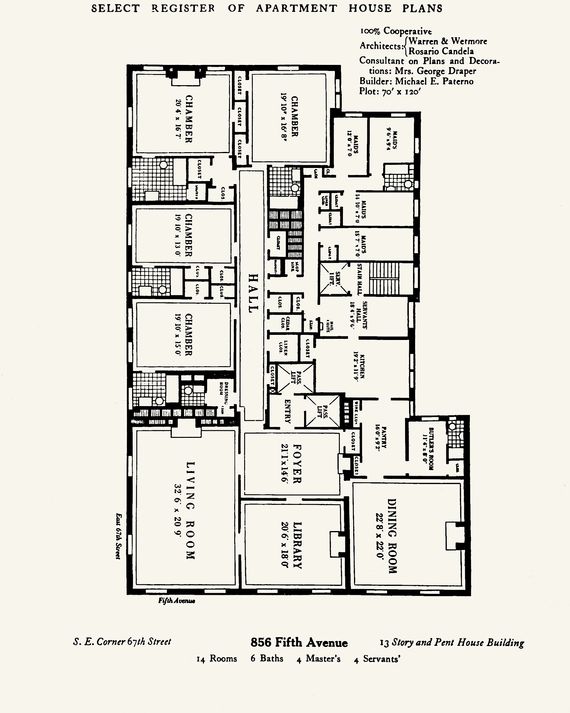

So even though my introduction to Candela’s work was from the outside, as I learned more I realized that was not even half of the story. Because his architecture and the nature of his gifts as a designer can only be understood by appreciating the interconnectedness between the massing of his buildings and the mystery behind their façades (is that a water tower, or the most romantic room in the city?) — to come to know them from the inside, by studying their plans, which reveal all. But finding these plans took time, and the view from the street was a good place to start, because nothing can arouse curiosity more than looking at the façade of a building one wants to get to know. It made me a passionate investigator. The patterns of windows and the spaces they masked were a riddle I very much wanted to solve; the terraces and their relationship to the layouts inside, a mystery I wanted to get to the bottom of. Most specifically, what became of the typical apartments that stacked up to form the base of the building as they morphed into setbacks above the 11th or 12th floor? Were those apartments better, each one unique, or were they somehow still like the ones beneath? The answers finally came (as many of them do) at Columbia University’s Avery Architectural and Fine Arts Library, where in 1987, while researching a paper at Sarah Lawrence, I discovered their set of the Select Register of Apartment House Plans.

We learn more from the floor plans than the exteriors because, like most and maybe all great architects, Candela designed with logical underpinnings and rigor equal to his aesthetics. Using this metric, he was the most gifted apartment house planner there has ever been. He possessed extraordinary powers of spatial organization, using them to conceive room arrangements that follow a certain formula to create what we might call the “off-the-foyer” layout. This method of laying out apartments around a central reception space that acts as a “fourth room” in the ensemble of living room, dining room, and library was not Candela’s invention; it was developed by his peer, the architect J. E. R. Carpenter. But Candela perfected it.

Before Carpenter, a New York apartment might have had no hierarchy between front- and back-of-the-house spaces. Or there might have been a corridor running the length of the apartment, off which all rooms opened. You might have had to cross this corridor to get from the kitchen to the dining room, inadvertently looking as you did so into the open door of someone’s bedroom. Like Carpenter’s floor plans, which in 1912 crystallized his ideas for superior apartment planning in the design for 635 Park Avenue, Candela’s also adhere to certain consistent principles for dividing the apartment into discrete areas for entertaining, service, and private life. But Candela was the superior planner, refining Carpenter’s principles ingeniously by resolving things like the means of getting from the kitchen to the living room without having to pass through the dining room, so that drinks could be cleared or a fire lit for after dinner.

These abilities — or at least those emanating from the same area of the brain — also found expression in Candela’s parallel life as a cryptographer. In the 1930s and 1940s, he wrote two books on the subject, and taught three courses on cryptanalytics at Hunter College during World War II. Problem solving in an obstacle-ridden environment came naturally to him.

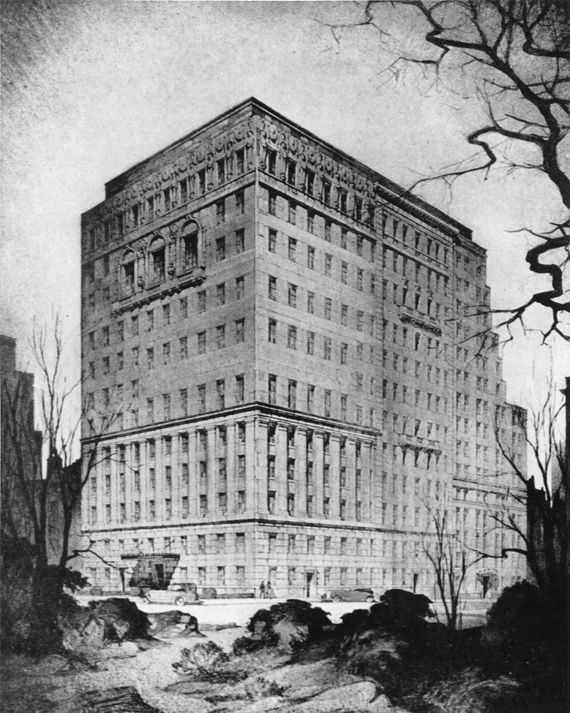

The most unusual thing about Candela, however, is his duality as a designer. While a gifted architect might typically excel at devising either brilliant plans or handsome elevations — one thing or the other — Candela was not only the best apartment planner, he was also one of the great romantic givers of form to New York. His sensuous instinct for external expression is reinforced by the sensitive detail of his buildings at street level, but more dramatically by their massing into terraced setbacks in the higher stories — ironically, in response to a constraint, the New York zoning regulation of 1916. The series of buildings representing Candela’s best-known work are where he developed, beginning in 1927, the now-familiar (but at the time totally innovative) residential form: the terraced setback crowned with a penthouse water tower. Deployed in commercial office towers in the Financial District, this device had not been used for a residential building before Candela did so on the easternmost section of 960 Fifth Avenue, which contained rental apartments using the separate side-street address 3 East 77th Street.

The towers of 770 and 778 Park, which inspired Paul Goldberger to invoke and identify an architect no one knew, and those of 834 and 1040 Fifth Avenue, which inspired Robert A. M. Stern to revitalize high-end limestone-clad apartment houses as a building type with his own designs, are — in contrast to their rigorous internal planning — dreamlike. Think of the famous sequence in the 1936 film Follow the Fleet where Fred Astaire and Ginger Rogers dance on a terrace in front of a lantern-like illuminated tower: This penthouse set is directly inspired by Candela’s Park Avenue skyline.

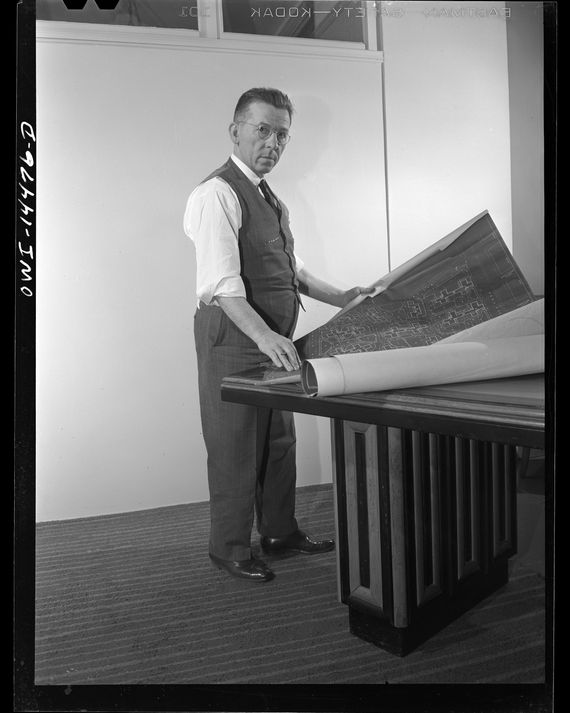

Where such decadence sprang from is anybody’s guess. Candela himself was a rather severe, crew-cut family man, not prone to Hollywood theatrics or excess in his personal style. It is hard to think of a greater contrast between personality and product: Julia Morgan and her work for William Randolph Hearst at San Simeon come to mind. But from this outwardly modest architect came visual drama that gave rise to a mythical idea of living well in New York City. Candela’s buildings define the image and character of the Upper East Side in our era as much as they did on the day they were completed — to no less a degree than the great stone skyscrapers of Wall Street, or Emery Roth’s sheer towers on Central Park West.

Planner, Innovative Form-Giver, Urbanist

The first mention of Rosario Candela in an analytic vein was Paul Goldberger’s, as I mentioned. Andrew Alpern’s monograph The New York Apartment Houses of Rosario Candela and James Carpenter (2001), on which Christopher Gray and I collaborated, provided a catalogue raisonné of Candela’s body of about 75 buildings; Michael Gross’s genre-busting 740 Park: The Story of the World’s Richest Apartment Building (2006) delivered the riveting social history, basically a biography of an apartment building. But the great book Candela’s work richly justifies has yet to be written. Perhaps it is this book, as I hope, which will close that gap.

The idea for a book decoding Candela’s genius, focusing expressly on the buildings that count, was born on an early summer evening on the steps of the Museum of the City of New York in 2018, after a panel discussion arranged to launch the exhibition “Elegance in the Sky: The Architecture of Rosario Candela.” Peter Pennoyer had designed the exhibition, and he and Paul Goldberger had just spoken on a panel that also included Elizabeth Stribling, who knows the apartments well from having sold so many of them. The talk had been most interesting, and attendance was standing-room only, with people all the way up the stairs. The most memorable feature of that show was a visual tool that broke new ground in explaining the ingenuity of Candela’s architecture: Peter and his office produced a film dissecting the sectional diversity of 960 Fifth Avenue, where the windows of each apartment lit up individually as the units with wildly different ceiling heights were discussed by a narrator. It was an MRI of the building, so to speak, investigating it in tranches and illuminating with total clarity the features that make 960, in my opinion, Candela’s most interesting project.

How are we to describe these buildings? They belong to a specific building type, which is the New York steel-frame and masonry-clad highrise apartment house. But why are Candela’s worthy of special consideration? A good number, in fact, are not so special — Candela was capable of serviceable, attractive work on a budget, and most of his commissions before 1926 fall into this category, with the conspicuous exception of 1 Sutton Place South. (It is worth mentioning here that the dates we use throughout this book are the dates Candela filed the building plans with the city, not the dates of completion.) But the handful that are masterpieces are important works of architecture because they transcend their own typology and exist in a super-category by themselves. Chief among these is 960 Fifth Avenue. The three-dimensional puzzle box of its plans and ceiling heights is unique in American architectural history, with the advent of the setback aspect on the side street — Candela’s first use of this device — ensuring the building’s significance externally as well. Rem Koolhaas’s identification of the “free section” in his description of the Downtown Athletic Club published in Delirious New York (1978) could be applied as appropriately to an analysis of this building — and indeed it should be, because there is no other way to interpret the design. Again, there is only one 960, largely because of the unusual circumstances of its birth as a co-op in which prospective tenants could specify and purchase blocks of vertical, as well as horizontal, square footage.

The buildings at 720, 740, 770, and 778 Park Avenue, all designed as rental apartments, are notable because they represent — just three years after Candela’s completion of 3 East 77th Street — the apotheosis of his setback and water-tower strategy in combination with plans of exceptional skill, if not sectional differentiation. There are two outliers: 1220 Park Avenue, often overlooked because of its location north of Carnegie Hill at 95th Street, but nevertheless a superior work where he applied the same formula as these buildings in terms of plans and massing, and 19 East 72nd Street, Candela’s only post-crash design which espouses all his principles as luxuriously — or nearly, anyway — as his pre-1929 buildings. It is also of special interest with respect to the involvement of associate architect Mott B. Schmidt, a very unlikely designer considering the modernist exterior vocabulary found here and at Candela’s 740 Park Avenue — and even less so, the plans.

There is a subcategory of buildings Candela designed on 30-by-100-foot townhouse lots such as 2 East 70th Street and 990 Fifth Avenue. These are worth a closer look because of what they teach us about his planning principles. In such confined, awkward sites, devised to hold a five-story house, what was important to him? What does an apartment with a footprint like this have in common with its much more generously proportioned cousins on Park Avenue? For one thing, the sequence of living room, dining room, and library is intentionally strung out across the longest possible distance, to provide the illusion of greater space.

If James Carpenter’s greatest innovation was his formula for the planning of apartments, Candela’s was his development of the terraced setback. This can be seen in its apotheosis on buildings such as 770 and 778 Park Avenue, both designed in early 1929. It is remarkable that Candela’s most significant contribution to the cityscape, and the signature architectural asset of these apartment houses, came about in response to an obstacle: the New York City 1916 Zoning Resolution. This regulation came about to keep streets from being cast permanently in shadow, after the sheer walls of the 1915 Equitable Building at 120 Broadway did precisely that. It required that a building constructed higher than one-and-one-half times the width of the street it faced be set back from the lot line at a point higher than what was typically the 11th or 12th floor.

Most of Carpenter’s apartment houses were constructed at a time when penthouse living had not yet caught on, and rooftop space was conventionally used for servants’ quarters. These buildings followed the example of an extruded Renaissance palazzo with a prominent roof cornice set by McKim, Mead & White’s 998 Fifth Avenue of 1910. However, by the time Candela reached the height of his powers in the late 1920s, the marketability of penthouses could no longer be ignored. Borrowing from the dramatic effect of Wall Street’s skyscraper district, and in response to developers’ need to achieve greater profitability through height, Candela developed the prototype for the New York setback penthouse, crowned with a roof tower. This combination of features put his architecture in the movies and embedded his buildings in the public imagination. Without them, it is safe to say, the Museum of the City of New York exhibition would not have been titled “Elegance in the Sky.”

We know Candela’s buildings represent a certain kind of urban luxury. But in what way, apart from that, do they constitute important architecture? Anytime I look at a building and think about the question of its importance (something quite apart from its likability or its beauty), I find it is helpful to ask two things: On what and how many levels does it signify? (Antoni Gaudí, for example, is not everyone’s favorite designer — but even if one doesn’t like his work, one has to respect its originality). And what would be missing if that building had just never happened? How much has it elevated, or perhaps even redefined its context? (Now try to imagine, whatever your opinion of him, Barcelona without Gaudí. It’s a trick question; you can’t.) And, with the passage and perspective of time, his architecture more than ever has the power to visually define the region of its birth and the image we have in our imagination of that city.

Turning our attention back to the New World, lower Manhattan without the stone skyscrapers of the Financial District would be an unimaginable non-landmark; the very definition of arrival in New York City is the sight of it from the Statue of Liberty. These buildings have been well documented and collectively classified, regarded now as ultimate manifestations of the architectural experiment that began in 19th-century Chicago when two inventions — steel-frame construction and the elevator — made tall buildings possible and opened the door to the modern city. No one today questions them as crown jewels of American architecture.

Any architecture that has the power to shape a city, or our perception of its part of a city, is important. And if any buildings have done that on Park Avenue or Fifth Avenue — made you blink, looking up, and then just as I did as a child, find yourself thinking about them long after you have moved on — there’s a very good chance they were designed by Rosario Candela.

More Great Rooms

- The Water-Tower Penthouse in the Bronx

- From a Downtown Loft to a Sutton Place Classic Seven

- The Santa Fe Home That Was Alexander Girard’s Final Triumph