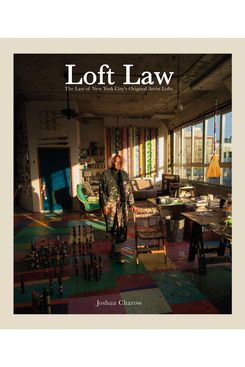

Joshua Charow’s book, Loft Law, The Last of New York City’s Original Artist Lofts, from Damiani Books, tells the story, through pictures and interviews, of the people who live in some of the most romantically bohemian spaces in the city. Many of them have lived in their lofts for decades, even before it was legal to do so, fixing up the drafty, derelict spaces. Gentrification followed, and landlords did their best to cash in, often by getting rid of these pioneers. So a band of artists got together in 1979 and worked to found what became the Loft Law in 1982, which helped establish the Loft Board to oversee the conversion of raw spaces into rent-stabilized residential homes.

“If you’re lucky enough to walk into one of their studios, you will be transported back to the year they moved in, to a New York that doesn’t exist anymore,” writes Charow in his intro. The book gives us “a peek into the wonderful worlds they’ve created and sustained in our ever-changing city.”

We chose three of them, from three different neighborhoods and decades.

Steve Silver

Williamsburg | Moved in: 1979

The elevator door opens to the top floor of a concrete building by the Williamsburg waterfront. To my right is a plain wooden chair labeled “new chair,” and beside it is a chair soaked in paint labeled “old chair.” A man with white fluffy hair, wearing a robe covered in paint and a tall blue beanie with a gold pom pom opens the door. Behind him I catch a glimpse of what looks like a huge multi-colored quilt, it’s his floor. This is the unique, vibrant, and whimsical world of Steve Silver, a painter who was born in the Bronx. He lives in a 5,000-square-foot loft that he moved into when Williamsburg was, as he describes it, “the wild west.” He has filled or painted nearly every corner of the loft, and there still isn’t enough space to hold his work.

In the early years, Silver lived with his girlfriend Chris Crowhurst, an artist who burnt sage and meditated in an 11-foot teepee she built, painted, and planted in the middle of the concrete space. Today, the teepee is gone, but there are plenty of bespoke objects Steve has installed over time. A rainbow striped broom is hanging from the ceiling. Two custom baseball bats

inscribed with the names of Marilyn Monroe and Albert Einstein are mounted on one of the walls. A balsa wood pterodactyl that Silver and his daughter Olivia painted seems to be floating in the air. Silver points at a stamp hanging from the ceiling and asks me if I know what it is. I look closer and see the name of the famed French artist, “Marcel Duchamp” engraved on it. “Well, that’s Marcel Duchamp’s stamp of approval!” Silver exclaims.

Silver works in series, and has large bright, colorful paintings and sculptures all over the loft. In the back studio he has a painting called Masquerade consisting of 112 pieces on a 12x16 foot wall. This was the first series he made after moving into the loft.

Over the past year, the building has been renovated to attract a slew of wealthy new residents. A few floors below, a loft half the size of Silver’s was rented for $11,000 per month. The renovation started with a scaffolding that surrounded the entire building. Silver found three rusted scaffolding connectors on the roof and painted them. The owner of the scaffolding company then gave him seven more, which he continued to paint. They looked so good to him, that he ordered 130 from a company in Texas, learned how to create rust, and on my second visit I saw 111 of them that appeared to be growing out of his floor. In my time with Silver, we discussed how to keep longevity as an artist. He tells me it’s like a calling. He wakes up, has a coffee and a tea and gets to work — no matter what. This philosophy makes him one of the most prolific artists I came across.

JG Thirlwell

Dumbo | Moved in: 1987

Down the hall from Curtis Mitchell’s loft in the former ice cream factory is a small door that says “Employees Only.” At first glance, it looks like a janitorial closet, but this is the entrance to Jim Thirlwell’s expansive loft and home studio. Thirlwell is a dynamic musician who has multiple musical monikers. In the 1980s, he was Foetus, an experimental and punk alternative to the rigidity of rock and roll. Now, he’s Steroid Maximus, a primarily instrumental ensemble that mixes classical and jazz to create a cinematic composition. He also works to score film and television. Thirlwell has incredibly intricate, unique arched windows that nearly reach his 14-foot concrete ceilings. He has built a home studio where he records, sometimes with an ensemble of other instrumentalists. Inside a back room of the loft holds thousands of vinyls, tapes, and CDs that Thirlwell has amassed over the years.

Thirlwell found the loft in a Village Voice ad in 1986. At the time, his tribe of musicians mostly spent time in Greenwich Village, and Dumbo was considered a no-man’s land. Interested in finding a space where he could build a home recording studio, Thirlwell signed the lease. “Loft living is not for everyone. I’ve seen a lot of casualties in this building, not physical casualties, but people who couldn’t handle it because it’s a commitment to live in a loft, and it’s rough. There’s not adequate heat, and it’s not like you can call up the super because there is no super. You’re responsible for everything in here, and not everyone wants a life like that. It’s kind of romantic, and you see this classic Hollywood image of New York living is like someone who is a waiter in a restaurant and lives in a loft like this, and everything’s fine and dandy. That’s just not the reality of it. It’s rough to do this. There was a guy that lived down the hall. Someone once came up the fire escape, came in through his window with a knife, and robbed him. He moved out. That was the end of it for him. So, it wasn’t for the faint of heart. People want comfort, you pay a lot of money for comfort, and you want to be able to call the landlord or the super when the plumbing isn’t working or when the electricity has gone out. So it’s a commitment to live in a loft—it’s still a commitment and still a lot of work.”

In the back of Thirlwell’s loft hangs a large “X” over the space. “That was built by Richard Phillips, who’s now known as a photorealist painter. That ‘X’ was built early on in his career. It was built as a prop for a play that was performed by Lydia Lunch called “South of Your Border.” In the final scene, Lydia was suspended, naked on this ‘X,’as blood was poured all over her. After the play concluded, the ‘X’ ended up living here at the loft. Where else was it going to go?”

Jennifer Charles

Greenpoint | Moved in: 2001

Jennifer Charles, the singer-songwriter who is half of the band Elysian Fields, nearly left New York City in 2001. Her lease had ended, and she was looking at shoebox after shoebox when she found a Victorian home upstate. Just before she decided to move, she got a call from a scientist friend who had decided to leave their Greenpoint loft. Charles made the decision to move into the raw, top floor, corner space where she continues to live with her partner, author Lance Scott Walker, and their two cats.

Charles’ loft is in an industrial corner of Greenpoint that managed to stave off gentrification until just a few years ago. Today, her building is now surrounded by glass towers. “In the 1930s, when it was built, this building was a rag factory. Back in the day, a rag man would go down the street and collect rags from people. Your old torn clothing, your dirty things, it was really about reusing and recycling and repurposing things. They would collect them from the neighbors, and then they would all be processed in the factory, and then everyone would have rags for what they needed.”

Her feelings towards Greenpoint of the early 2000s are reminiscent of older artists’ feelings for the Tribeca of the 1970s: “There was something about it that captured the imagination. This whole area was just completely a no-man’s land. It was very industrial. There were not even streetlights. I loved that you could just be down here and not run into anybody you would know. It was very special, and that lasted for [quite some] time. I can’t even remember when that ended, but it hasn’t been like that for a long time. Then, of course, Bloomberg sold the city up the river, and then all the subsequent mayors have done things just to have high rises in real estate and be in cahoots with the city council. They’re all scratching each other’s backs.”

The loft has been an instrumental part of Charles’ musical process. “We’ve had rehearsals here, we’ve had salons here, we’ve filmed music videos here, we’ve filmed music videos on the roof, we’ve done photo shoots here, it goes on and on. Of course, many songs and albums have been written here. There’s something so essential for me to be able to create at any time, in any moment that I want. If I wake up at night with a song, which often happens, I can just start working on it. And that’s very, very special.”

Around the late 2000s, artists and loft tenants across Brooklyn started to pursue the same fight as the original Manhattan tenants did in the late 1970s. After organizing, staging rallies, and again visiting Albany, the Brooklyn tenants won an amendment to the Loft Law in 2010 to expand Loft Law coverage to Brooklyn residents. It also created a new window for any loft tenant to gain coverage by proving they lived in a commercial or manufacturing-zoned space for 12 consecutive months from 2008 to 2009. Charles and many others who arrived after 1982 gained Loft Law coverage under this new amendment to the law.

Like others I interviewed, Charles says leaving this loft would mean leaving New York. “I don’t want to leave it because it continues to be a haven. If I had to leave this place, I would probably leave New York—and that’s the honest truth. It’s really a special community. Without sounding glib about it, it’s a sacred thing. We’re an endangered breed—being an artist in New York.”

More Great Rooms

- The Water-Tower Penthouse in the Bronx

- Rosario Candela Invented the Upper East Side Apartment

- From a Downtown Loft to a Sutton Place Classic Seven