In 1979, at a house party in a walkup in Little Italy, the writer Floyd Byars took a look around. Out the back windows, instead of the typical view, there was a strange sight. Not trash, or trees, but a building — abandoned, its windows black — that was completely invisible from the street. Finding it felt like “passing into a fold in the universe,” said Byars, who had been working on a novel, translating French, freelancing for The Village Voice, and watching artists buy up Soho. If this building was empty — couldn’t he and his friends make an offer?

Back then the neighborhood around the building — stuck squarely between Spring and Kenmare, Elizabeth and Mott — was still the kind of place where guys who grew up in tenements nearby gabbed at Spring Lounge and watched the block over cappuccinos. Byars, a hustler and a people person, started asking around. Who owned the place? How could he get back there? A tip led him to knock at 18 Spring Street, a 19th-century tenement with a narrow hall. The owner, Byars remembers, had a “very disgruntled look,” and no interest in some college kid asking about an architectural wonder.

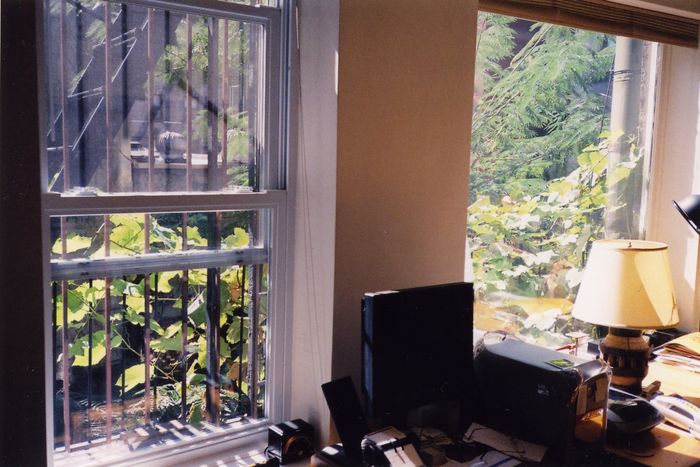

So Byars kept looking at other places to buy and treated the building behind 18 Spring like an oddity, taking friends on sneaky tours — including his college buddy Patrick Hickox, down from Boston, who remembered the building as a “very intriguing secret that Floyd was sharing with me.” Hickox had just gotten his master’s in architecture at Yale and appraised the five-story brick building to be a classic tenement with cast-iron lintels and a façade that was “strikingly handsome.” Inside, each floor had two narrow dark railroad units that stretched back and shared a bathroom. Hickox dated the building to a few years after the Civil War, and papers at the Department of Buildings indicated it was there by 1877 — when immigrants were arriving downtown, causing a building boom that meant tenements were sometimes built with so-called “rear tenements” that got even less sun and air than the ones in front. These back buildings became housing for the most desperate — photographed by Jacob Riis for How the Other Half Lives, and first to be torn down when regulations enacted in 1901 went after ventilation, plumbing, and fire-code issues. A survey found 61 rear tenements in Little Italy in 1990, though it’s unclear how many still stand — the area isn’t landmarked, and developers focused on price per square foot would seem motivated to tear them down. Especially if they’re thinking about the cost of construction, which, on a back building, requires carting all the material through the sometimes narrow passages of front buildings.

But Byars wasn’t a developer; he was a romantic and saw the building’s hidden entrance as its advantage. A few months after he first knocked on the door of 18 Spring Street, he got a knock on his rental. It was his landlord, who wanted to know if he was still interested in buying the building. Byars’s girlfriend asked the landlord how he knew about any of this; what the landlord said next never left him. “We know everything you do in the neighborhood.” The landlord also knew, supposedly, that the mysterious owner of the back building had “been playing cards with people he shouldn’t have,” Byars remembered, and needed to generate cash within a month.

Byars started recruiting partners to make an offer. “I ran into him at some bar,” said Pryor Dodge. He had known Byars from Paris — when Dodge was playing flute professionally, and hanging out with mutual friends at a small, student-friendly hotel. His father, Roger Pryor Dodge, was a jazz dancer whose photographs became the most extensive visual record of the dancer and choreographer Nijinsky. Some of his father’s shots were in a flat-file, along with Dodge’s own stuff, photos taken as a kid in Greenwich Village that became an important postwar account of downtown life, now in an archive. Plus, Dodge had antique furniture, and the start of what would become a massive collection of early bicycles, which has since toured museums. He needed space and wanted a floor and a half at the ground level, plus storage in the basement. “The price was right,” he said. “And it was very charming.” Other friends took floors above Dodge and a studio behind him, and Byars took what Hickox generously described as the “penthouse,” hiring his old architect pal to design plans that would loft his bed over a dressing area, carve out a nook for a study, and elevate a dining area for drama. “Floyd has a rich and complex imagination, and the apartment is that — on a modest scale,” said Hickox, who called Byars’s 700-square-foot unit “Piranesian in its complexity.”

The partners recruited locals to do the work, finding a general contractor who “modeled himself after Billy Joel, and really looked like Billy Joel,” Hickox remembered. “He was a very endearing and wonderful person.” Only, he had never been a general contractor, and hired a guy to build the stairs who forgot about the two inches added by finishing materials — making the stairs illegal. They hired an artist who sidelined as a plumber to do the work — but the guy backed out, and recommended a friend who stopped showing up, forcing Byars to track him down to “a crack den off Bleecker with a bunch of hookers” — a scene he described as so clichéd as to be “Damon Runyan–esque.” When the work finally reached the roof, the roof collapsed, remembered Dodge, who by then was overseeing the construction locally. Byars had since moved to Los Angeles to work with Tarkovsky’s preferred screenwriter — Andrei Konchalovsky, and when the building was done in 1985, he rented his unit out, expecting to return soon. Dodge became the default super — overseeing the garden and managing affairs for a rotating cast of creative New Yorkers. Some bought from Byars’s friends, others rented — the building didn’t have the stodgy rules of a co-op, since Byars had founded it as a rare partnership condo. There were five units over five floors: The top three floors had one-bedroom floor-throughs, including Byars’s “penthouse,” and on the bottom two floors, there was Dodge’s duplex, with a private front entrance, plus a cozy studio carved into the back of the first floor.

Byars remembered the writer Jody Shields, the actor Chiwetel Ejiofor, and Anne Roiphe, whose daughter Katie was there, too. Will Frears, the theater director, first saw the place in 2001. A sticker on the front of 18 Spring Street at the time read “WASTED TALENT,” and Frears, just out of grad school and working in restaurants, fell in love. “It was so eccentric, so strange, so charming — the fact that it was available seemed sort of magic,” he said. “In a 1950s way, it was an artist apartment,” Frears said. “I got quite a lot of artistic validation that I wasn’t entitled to.” The composer Michael Friedman came over to teach a regular music class over Chinese food — a kind of book club where the friends would prepare by listening to Tristan und Isolde, then learn from Friedman about its history and theory. And Frears was living in the place when he opened a copy of Time Out to see that the two plays he was simultaneously directing had made the magazine’s top-five list. “I remember thinking, I should retire now,” he said.

Pryor Dodge moved out in 2007, selling his duplex to a doctor who was then running the emergency department at Beth Israel, Gregg Husk. “When I walked in and saw the garden for the first time, it was over for me,” Husk said. “There was no rational thinking.” The architect Massimiliano Locatelli was living on the third floor at the time and had updated his unit impeccably. He was happy to renovate the Dodge apartment — turning the ground floor into a study, walled in by built-in bookshelves. For the kitchen, Locatelli created a metallic jewel box inspired by food carts, turning a steel bent into a diamond quilt pattern into a wall covering that stretches from floor to ceiling.

When the architect moved out in 2013, he sold to the artist-chef Laila Gohar and Omar Sosa, the editor of the cult magazine Apartamento, who told the New York Times the apartment was “pristine” when they arrived but hired the artist Sam Stewart to add quirk. Stewart designed a custom sofa, a magnetic knife strip shaped like a hand, and a door fitting for a princess’s tower — a pointy Gothic arch upholstered in brown and gold leather, which they seem to have left behind when they moved out a few years ago. (Gohar, who didn’t respond to an email, offered the unit as a sublet around the time that she and Sosa broke up.)

Husk found over the years that he was home more than the other owners — and used the garden more, too, with a cat who liked to roam outside — so he took over Dodge’s duties as default superintendent, and eventually bought out Frears’s interest, too. But Byars, who has been living in Los Angeles ever since organizing the renovation, never sold. “I always thought maybe I’d come back,” he said. He had plans never fulfilled to put an “aerie” up on the roof, where zoning allows building a floor and a half higher — an idea that seems, year by year, to be less and less rational.

Byars and the other remaining partners, including Husk and Gohar, have toyed with selling over the past five years, and have now agreed — so the building is on the market in its entirety, leaving open the possibility that it could be demolished. But that seems unlikely. The secret, off-street location that once made this a likely tear-down is now a selling point. And so many other back buildings have since been demolished that Douglas Elliman broker Keren Ringler couldn’t find others in the area. “It’s totally unique,” she said. “What I love about the house is what I love about New York City. There’s always something new to discover, something unusual, a surprise. Our city still has these little secrets.”